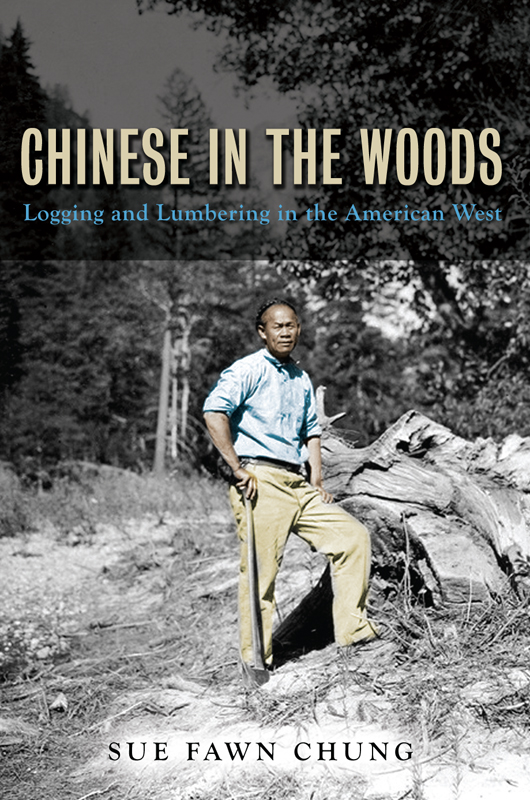

CHINESE IN THE WOODS

THE ASIAN AMERICAN EXPERIENCE

Series Editors

Eiichiro Azuma

Jigna Desai

Martin F. Manalansan IV

Lisa Sun-Hee Park

David K. Yoo

Roger Daniels, Founding Series Editor

A list of books in the series appears at the end of this book.

Chinese in the Woods

Logging and Lumbering in

the American West

SUE FAWN CHUNG

UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS PRESS

URBANA, CHICAGO, AND SPRINGFIELD

2015 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

c 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Chung, Sue Fawn

Chinese in the woods : logging and lumbering in the American West / Sue Fawn Chung.

pages cm. (The Asian American experience)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-252-03944-7 (hardcover : acid-free paper)

ISBN 978-0-252-09755-3 (e-book)

1. Foreign workers, ChineseWest (U.S.)History19th century. 2. LoggersWest (U.S.)History19th century. 3. LumbermenWest (U.S.)History19th century. 4. ChineseWest (U.S.)History19th century. 5. ImmigrantsWest (U.S.)History19th century. 6. Working classWest (U.S.)History19th century. 7. Lumber tradeSocial aspectsWest (U.S.)History19th century. 8. West (U.S.)Economic conditions19th century. 9. West (U.S.)Ethnic relationsHistory19th century. I. Title.

HD8081.C5C47 2015

331.6251097809034dc23 2015006371

For Alan Solomon, my invaluable helper

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The story of the Chinese in logging would not have been told except for the archaeological work that revealed much about the lifestyle of these men who left no written record. The United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Humboldt-Toiyabe Division, especially archaeologists Fred Frampton and Terry Birk working in conjunction with University of Nevada, Reno, Professor Emeritus of Anthropology Donald Hardesty and his graduate students, particularly Kelly Dixon, Ralph Giles, Jane Lee, and Theresa Solury, have augmented our knowledge. Former Olympic Forest Service Supervisor Dale Hom assisted in obtaining grants for the projects. The volunteers in the Passport in Time program lent invaluable assistance in uncovering material artifacts. Much has yet to be discovered and hopefully more work in the field will be forthcoming. Other archaeologists, especially Penny Rucks, Clifford Shaw, Carrie E. Smith, Susan Lindstrom, Priscilla Wegars, Barbara Voss, Paul Chace, Robert Morrill, and Mary Rusco were among the many who guided me in studying archaeology. Alexander and Alan Solomon joined me at the pit sites while I served as historical consultant.

The written records were also fragmentary. Professor Emeritus Roger Daniels introduced me to the importance and use of census data and other primary sources. Marian Smith, Immigration and Naturalization (INS) historian, showed me valuable INS resources. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) staff members at Seattle, Riverside (Perris), Washington, D.C., and San Francisco (San Bruno), especially Marisa Louie and volunteer Vincent Chin, were very helpful. Wuyi University sponsored a tour of several Siyi counties in Guangdong under the leadership of Jinhua Selia Tan; the tours demonstrated what occurred in the home regions of the Chinese Americans. The staff members of the Nevada State Historic Preservation Office (especially Ronald James), Nevada State Museum (especially Robert Nylen), Nevada State Railroad Museum (especially Wendell Huffman), Nevada Historical Society (especially Lee Brumbaugh), Nevada State Archives and Library (especially Guy Rocha), Storey County Courthouse, Washoe County Recorders Office, Ormsby County Recorders Office, Douglas County government offices, Truckee Historical Society (especially Gordon Richards), California State Railroad Museum in Sacramento (especially Stephen Drew), California State Archives, Shanghai University Library (especially Luxia You), Shanghai Public Library, Huntington Library, Bancroft Library, Ethnic Library at the University of California, Berkeley (especially Wei-Chi Poon of the Asian American Division), Special Collections at the University of California (San Diego and Los Angeles), Special Collections Divisions at the University of Nevada (Reno and Las Vegas, especially Su Kim Chung and Christine Wiatrowski), and the University of Washington, Seattle, all allowed me generous access to numerous archival materials. The University of Nevada, Las Vegas, and especially the History Department and Dean of the College of Liberal Arts, have been very supportive of this endeavor. Oral interviews with the late Professor Elmer Rusco of the University of Nevada, Reno, the late Frank Chang of Lovelock, the late Shirlaine Kee Baldwin of Berkeley, the late John Fulton of Tahoe City, the late Anna Kwock of San Francisco, former Forest Service Ranger Clifford Shaw, Ray Walmsley of Dayton, Robert Morrill of San Francisco, Andrea Yee of Berkeley, Landon Quan of Santa Rosa, John Fong of Carlin, the late Henry Yup of Reno and Lovelock, Rowena Chow of Los Altos Hills, Dennis Wong of San Marino, and Ynez Lisa Lai Chan Jung of San Rafael added insights into this project. I am indebted to Nicholas Menzies, James Rawls, Yong Chen, and Evelyn Hu-Dehart for their comments. University of Nevada Reno graduate student Ralph Giles was extremely helpful with Carson Tahoe Lumber and Fluming Company documents. Several of my graduate students at the University of Nevada Las Vegas, especially Philip Lockett and John J. Crandall, also uncovered information for this project. Special thanks go to Annette Amdal, UNLV History Department administrator, and the editorial staff at the University of Illinois Press, especially Laurie Matheson, Thomas R. Ringo II, and Julie Gay for their invaluable assistance.

Roger Daniels, who introduced me to Asian American history, contributed the title for the book. Alan Moss Solomon drove me to many sites throughout the American West and British Columbia so that I could do the research, and he helped in editing the first rough draft. For all of his efforts and support, I have dedicated this book to him.

NOTE ON TERMS, NAMES, TRANSLATION, AND TRANSLITERATION

Chinese names can be complicated. In China the family name, being the most important, was stated first, followed by the first name, usually composed of two characters, hence two words. A few Chinese surnames, such as Ouyang (Cantonese Owyang) and Sima (Cantonese Seeto), are polysyllabic. The formal name often indicated generation and birth order for males. Males also had a familiar first name. Other names, such as a nickname, school name, birth order name (such as Li SanLi number three) or studio name, might be adopted. Ah was a term of address, not a name, but the general American public was unaware of this and mistakenly believed it was a Chinese first or last name.

In general, if the Chinese characters are known, the last name is given in pinyin Romanization (officially adopted in China in 1949) first (in Chinese tradition), often with the Cantonese pronunciation or American version in parenthesis with the exception of well-known people such as Sun Yatsen. The last name of individuals can be variously spelled so that, for example, Wu in American documents could be Ng, Ang, Ung, Ong, and Eng, or Chen can be Chan, Chin, Chinn, Chen, Chung, but the pinyin permits uniformity. The exception is the Yu/Yi clan in Nevada, where the common American Yee is used, since the characters for all of the names were not available. If only the transliteration is known from English language sources, the name is given as written and usually with the first name first and family name last. There are one hundred common family names in China. Kee is not one but comes from immigration officials and often is seen in government records. Most names on the census were distortions or adaptations of formal Chinese names. Consequently, it has been difficult to trace individuals for two or three census periods. The census takers randomly spelled the name as they heard them. Complications arise when American government officials reversed the names, so that Joe Shoong (Zhou Song in pinyin, 18791961), one of the early Chinese American millionaires in California, got the family name of Shoong (his Chinese first name). A few Chinese took American first names. An even smaller number adopted American first and last names, either because they worked primarily with Euro-Americans or took the first step in Americanization. Jim Humbold and William Poor were examples of men who adopted American names and lived in the boarding house with other Chinese who worked in logging in Virginia City, Nevada (Census 1870). Jim King, a Central Pacific Railroad (CPRR) foreman and labor contractor of Locke, California, originally from Zhongshan, and Billy Ford, a railroad supervisor in Sparks, Nevada, originally from Kaiping, were known by their American names and had adopted an American lifestyle for themselves and their families. Men also became known by the name of their business. Dr. Wing Lee of Portland and Salem, Oregon, was a Chinese doctor who arrived in 1862 or 1864 with the family name of Zhang (in pinyin; variously transliterated in Cantonese-English as Chang, Chung, Jung, Cheung, Chiang, and other spellings) and the full name of Zhang Liang Rong Li (Liang was his first name, Rong Li was his mothers name), using the traditional order of names with last name first, but known to Oregonians as Dr. Wing Lee.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.