Contents

Guide

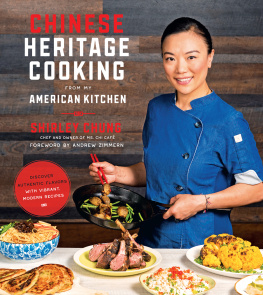

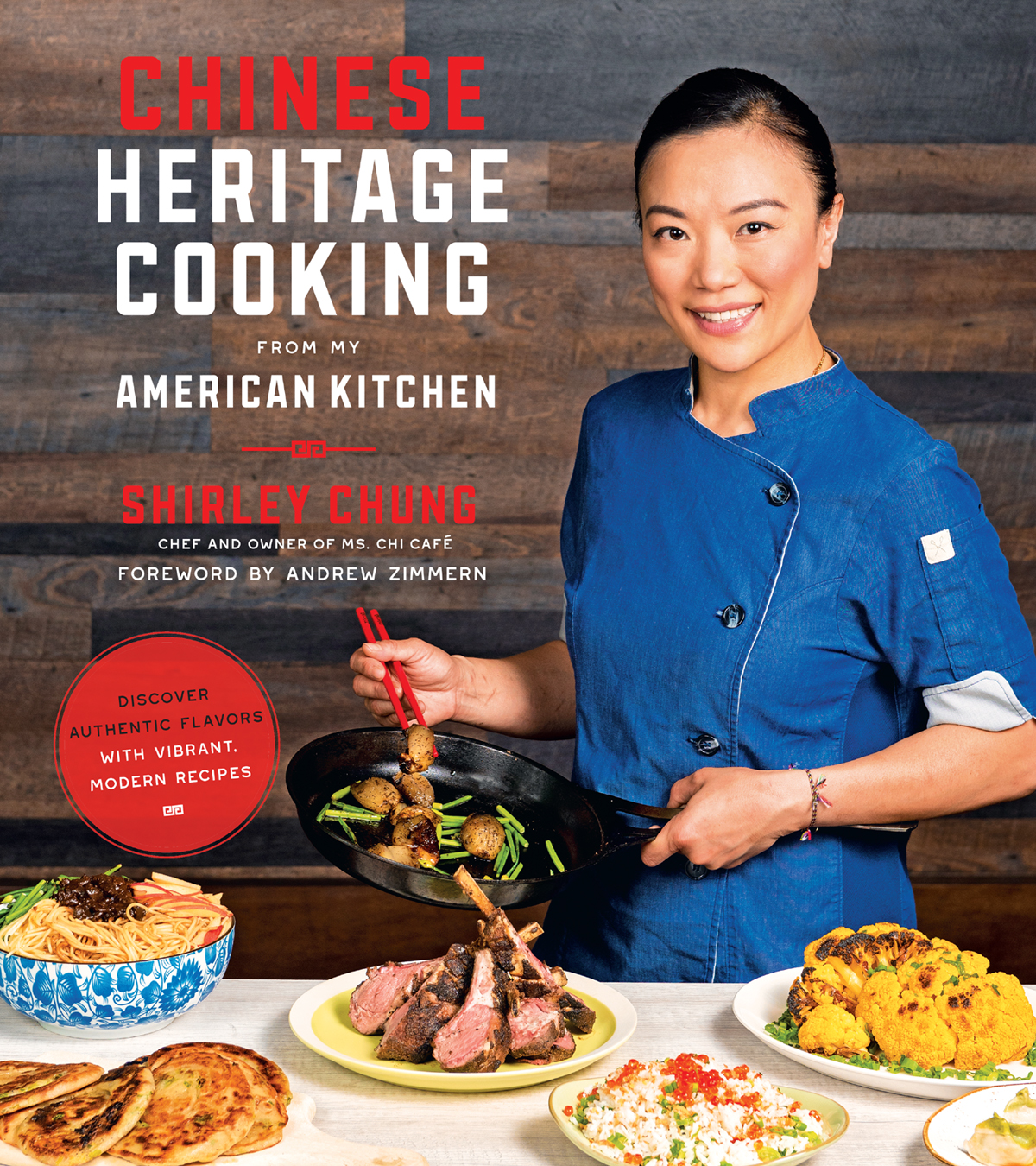

CHINESE

HERITAGE

COOKING

FROM MY

AMERICAN KITCHEN

DISCOVER AUTHENTIC FLAVORS

WITH VIBRANT, MODERN RECIPES

SHIRLEY CHUNG

CHEF AND OWNER OF MS. CHI CAF

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: http://us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

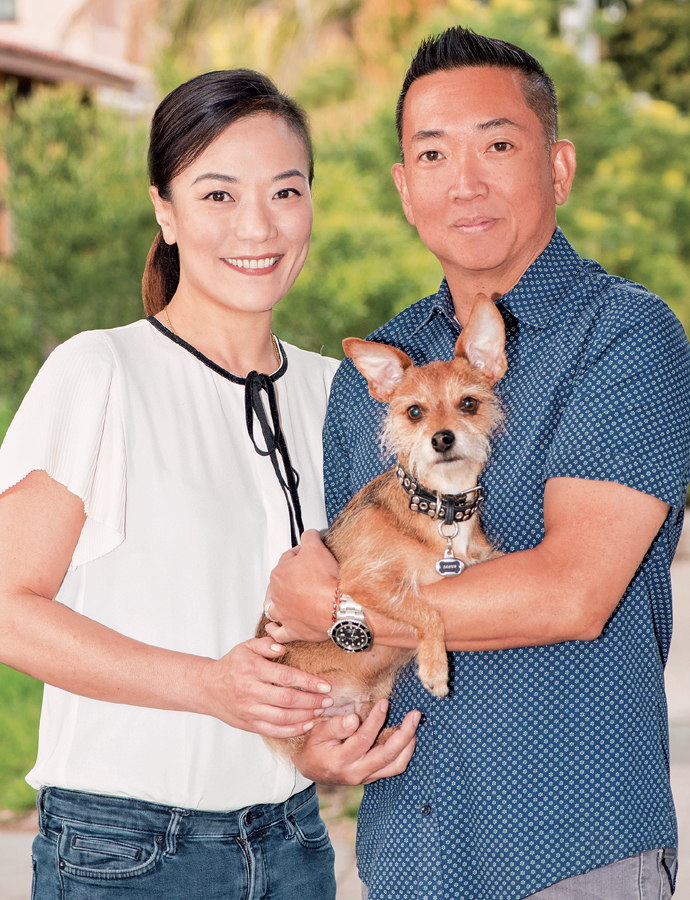

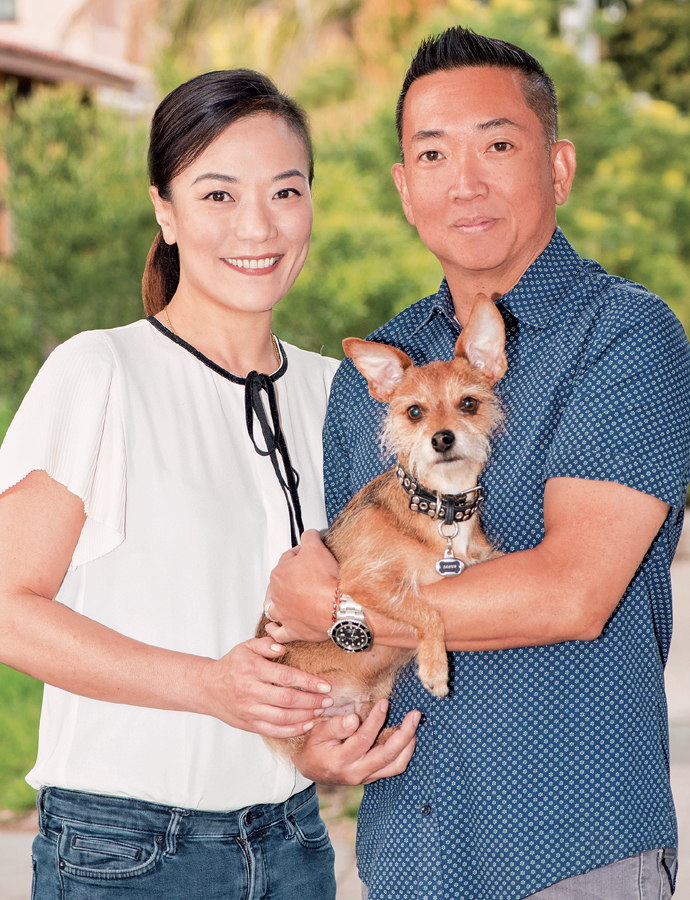

This book is dedicated to my grandma Silvia Siyi Liang, who introduced the world to me through food and culture. Its also dedicated to Jimmy Lee, who constantly pushes me to be better; you are my rock, my foundation.

From the moment I first met Shirley Chung through her work on Top Chef, I knew she was going to leave a mark on the food industry in a big way. As we got to know each other, I realized that her being born and raised in a supersized city like Beijing, China, must have prepared her in many ways to succeed in the restaurant world of America as an immigrant and a woman. Sure, immigrants and women have and continue to be the backbone of the food service world, but in the world of fine dining, the hierarchies are patriarchal. By working her way up the ladder, proving and reproving herself, and putting up with the slings and arrows of daily restaurant life, her skills were quickly mastered. Her talent for leadership and cooking became clearly defined, grown and honed to a razors edge. She was part of the opening team at Thomas Kellers Bouchon, Mario Batalis chef de cuisine at Carnevino and the chef at Jos Andrs China Poblano in Las Vegas, to name a few. Bravo gave her a shot in Top Chefs season 11 and again in season 14, and a star was born. With her infectious smile, quick wit and unselfish spirit she became a fan favorite. The post-TV years have been filled with ups and downs, some restaurant projects abated, a new dumpling restaurant called Ms. Chi Caf opened and now this book. So shes a TV chef, right? Dead wrong.

Chefs in America today, if they have the talent, are invariably sucked up by the modern media machine, packaged and presented. Many are emperors with no clothes, many others are some of the most serious, bright and earnest culinarians in our country. Those characteristics dont make for great TV in the competition genre, where challenges often dont showcase the best aspects of what it means to be a chef, a true leader, inspiring and dedicated to the craft of making and sharing great food. Shirley Chung is a great cooka superb chef, in factwho happens to have been on TV, and this book is all the proof you need if you havent been able to meet her or taste her food.

Shirley found her voice, her style and her point of view on TV because it forced her to have an internal reckoning. What do you want to say as a chef? is the question I always ask when mentoring young cooks with giant-sized aspirations. Shirleys upbringing in China, her move to America as a teenager, her short-lived career in the tech world and her many years of cooking in some great restaurants forced her to answer that question in front of a global audience. Soulful Chinese heritage cuisine, shot through the prism of American modernist cookery, is her niche. Rather than seeking to be the authoritative voice speaking for all eight major regions of Chinese cooking, she chose her own path, guided by her own experience, a vital decision that should be a signpost for all cooks to follow. The results of that choice are in your hands.

In this book Shirley makes the case, brilliantly, of when to be honest and authentic and when to simply make great food thats relevant to our way of eating and celebrating in America today. Her simple attitude about when to wok and when not to, along with her master class on noodles, are testaments to both sides of the equation. Woks arent a necessity; there are many ways to achieve the effects . I had the same reaction that she did when I tasted my first version of this dipping sauce in south-eastern China over twenty years ago. The crunch and piquancy of the pickled radish swimming in a soy-based, herb-spiked puddle of flavor reminded me of regional salsas I had eaten in Mexico, more philosophically than flavor wise, but achieving the same effect. The perfect companion for many foods, this sauce can be served with anything. Beholden not to tradition, but to the exacting demands of flavor and texture and the ultimate litmus test: Does it taste good? And does it work for the way we eat today? It sure does. Make a big batch and keep it on hand in the fridge. I use it on day one for dipping boiled dumplings and on day four as a marinade for meat before grilling. Its brilliant.

As is her . Asparagus with black bean sauce is a Chinese classic, and the sauce itself has become a bedrock of Chinese American cookery. The simple, salty-sweet sauce, a flavor bomb that acts as an accelerant to the explosion of flavor from the years first asparagus, the umami of the fermented beans everyone loves this dish. In fact, a version of it was the very first solid food my son ever ate. The addition of a fried egg, which to some might feel clichd, is a superb choice. The crispy-edged whites and the runny yolk are a perfect platform for the sweet vegetal asparagus and a superb foil for the accessible funk of the black bean sauce. There is a real statement being made here by these and all the other recipes in the book.

Chinese American food is as valid and historically relevant a cuisine as any other. Yup, I said that. Let it sink in. Like Tex Mex, or a handful of other hybridized cuisines with a lengthy history and even more important legacy, it stands on its own. Thanks to 160 plus years of Chinese immigration to America, the 1882 law that halted immigration after the first wave and the rampant racism that created it, Chinese Americans settled into tight-knit communities and used entrepreneurship to establish business links within those communities and in the surrounding neighborhoods and cities. Creating laundries and restaurants were primary avenues of upward mobility, and foods were tweaked and developed for American palates, from Egg Foo Yong to Chop Suey, from Egg Rolls to Sweet & Sour Chicken. These were the vehicles for acceptance into an American society that inhales other peoples cultures from around the world first and foremost on the end of a fork. For generations, Americans ate Chinese food almost universally designed not for subsequent waves of immigrants (that would come later) and not representative of true regional Chinese cooking that would explode after Nixons Chinese sojourn in the early 70s, but for people who looked like me.

This is not food to be ignored. Its food to be celebrated and enjoyed. To treat it any other way would be to ignore the history, both good and bad, of the immigrant experience in America. As importantly, it would cast aside a whole world of flavors and dishes that are delicious and universally beloved. Even worse, it would invalidate the lives and loves of chefs and people like Shirley Chung, a brilliant and caring cook, a true culinarian who represents everything I love about this country and our pursuit to make the invisible known, to take the hidden and make it seen.