All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form, or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Data is available.

For my parents, who abandoned their success stories in order to feed ours.

And for Eric, Meilee, and Shen, who light my way.

Foreword

In The Primrose Path in 1936, Ogden Nash writes, Her pictures in the papers now, and lifes a piece of cake.

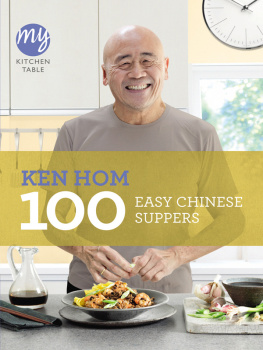

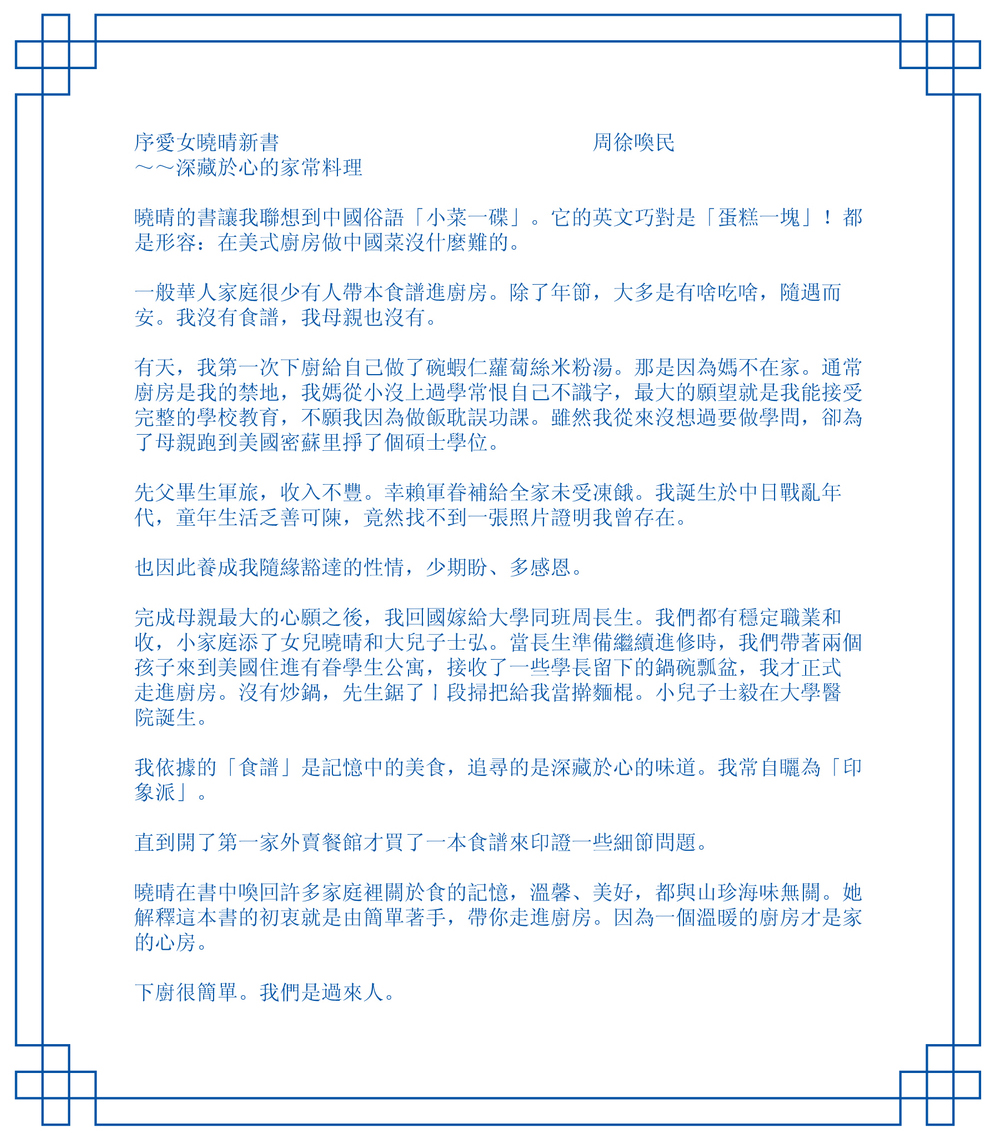

While reading my daughter Hsiao-Chings cookbook, I thought about this quote because her message, ultimately, is that cooking Chinese food in a Western kitchen is not as hard as it may seem. Most Chinese people go into their kitchens without ever consulting a cookbook. I dont. My mother certainly didnt.

The very first dish I ever cooked for myself was a bowl of rice noodle soup with daikon radish strips and a few pieces of dried shrimp for flavor. It was only because my mother was not home that day that I had to feed myself. The kitchen was normally off-limits to me. The wok was there, and the stove was there, but my mother never let me touch them. Her biggest regret was that her circumstances prevented her from attending school, so her dream was for me to complete my formal education. She didnt want me wasting my time in the kitchen. So, even though I had no ambition for becoming an academic, I reached graduate school and earned a masters degree (from the University of Missouri School of Journalism) for her.

My father was a military man with a limited income. Luckily, our family received a small stipend for military dependents that helped. I was born during the Sino-Japanese War, and I didnt even have a single photo to prove my existence. Thus, my character was built on the value of not asking for too much in life and appreciating whatever I may receive.

After I fulfilled my mothers dream, I married a man Id met in college. We both had steady jobs and fair incomes, so we started a family and had Hsiao-Ching first, then her brother, Shih-Hung. When my husband decided to pursue his masters degree (also at the University of Missouri), we set forth on our future life in the United States.

With my husband in school and two young children in tow, I eventually gave up my career as a journalist. That was when I started taking cooking more seriously. We were in a campus apartment with some hand-me-down cookware, but no wok. But I tried every way to feed my family, including making dumpling skins with a sawed-off broomstick as a rolling pin. Our third child, David Jr., was born at University Hospital near campus.

The only cookbook I always had was my memory of good eating. So I joked that I was an impressionist cook. It wasnt until we opened a small carryout restaurant that I even bought a Chinese cookbook to double-check some details related to techniques.

Hsiao-Ching explains that the purpose of this book is to encourage people to get into the kitchen and start cooking. Thats what we did, and so can you. I am mostly touched by the fond family memories she has brought back with her stories. A warm kitchen is the heart of the family. And that is sweeter than cake.

ELLEN CHOU

Introduction

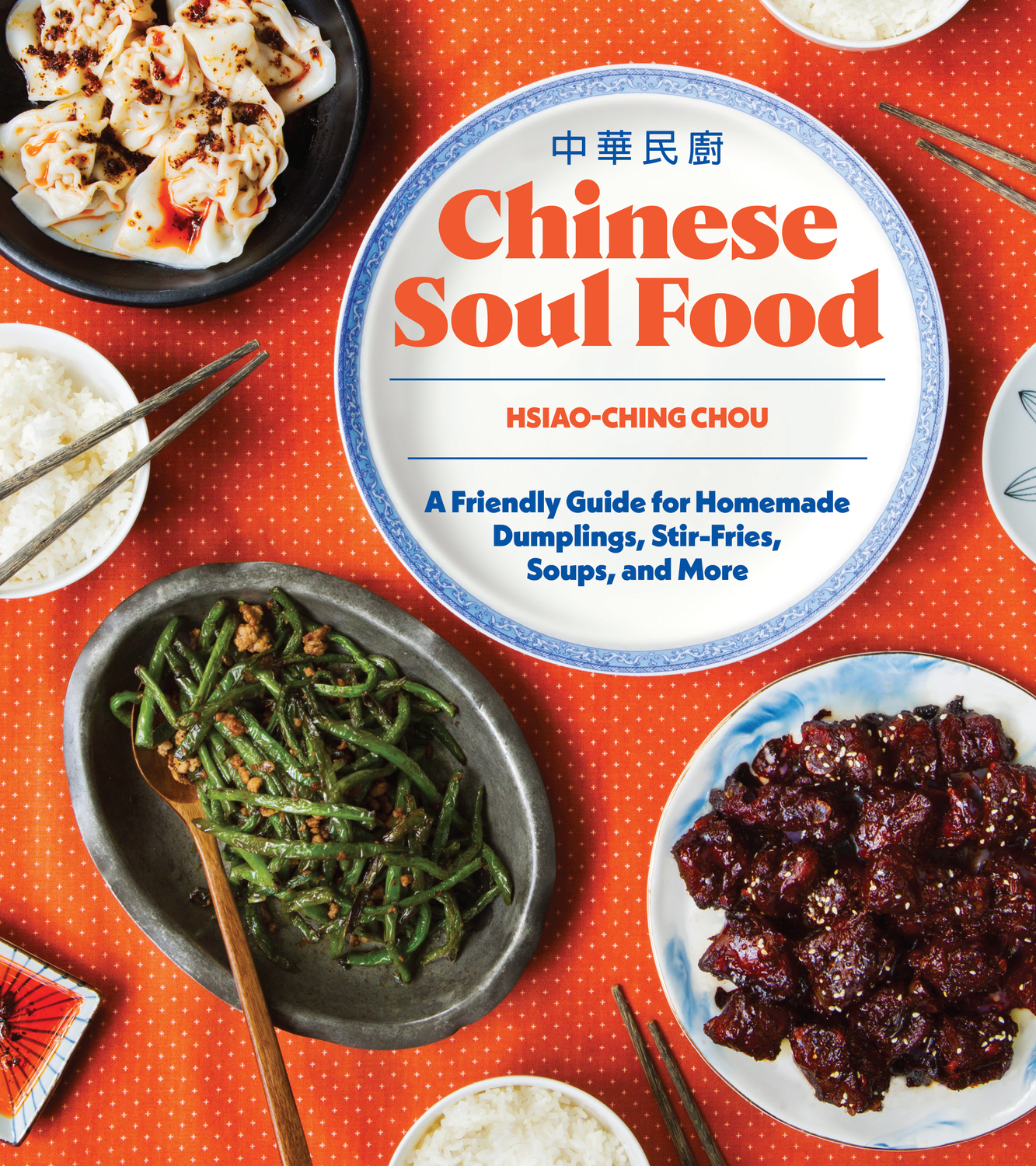

Growing up in my familys Chinese restaurant and then becoming a professional food writer did not give me license to write a cookbook. I had the ingredients, so to speak: an immigrant story, restaurant credibility, a journalism degree, a food column in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer newspaper, a fan base, an agent, even polite interest from a couple of New York publishers. But I had nothing to say.

It wasnt until after I had gotten married, had two children, quit the newspaper, and changed career paths a couple of times that the cookbook declared to me its need to exist. Life had taken me on the scenic route toward this end, and it began with the Chinese Soul Food blog in 2007, which I had started in hopes of maintaining my weekly practice of writing and providing a hub for my fans. I also wanted to create a space to share straightforward but comforting recipes inspired by foods I ate growing up. The ingredients wouldnt break the bank, and the recipes could be made, possibly, with a small child literally wrapped around your leg or while wearing a baby in a sling. That scenario was a reality for me at the time. Money was tight too, so I had to be resourceful about ingredients. I knew that the Chinese cooking I had grown up eating could be extremely economical, considering many stir-fries are vegetable-centric with meat only as a condiment. I figured if I needed such a resource, there probably were other parents out there in the same boat. Despite a good start, the blog suffered from neglect, especially after I had a second child. So it went dormant until 2015, when the opportunity to teach regular classes on Chinese cooking at Hot Stove Society, an avocational cooking school in Seattle, revived my need for a recipe blog.

When I was at the newspaper, my column was a weekly trigger for home cooks to reach out to me with questions or comments about recipes of all types. I learned as much from the readers as they learned from me. After I left the paper, that channel of exchange became nonexistent. It took five or so years away from the day to day of journalism to give me the perspective I needed to understand what I had missed about being a columnist: telling universal stories through the lens of cooking, eating, and thinking about foodand, more importantly, being in a position to convey cooking skills to a broad audience in order to empower them to feed themselves and their families deliciously, simply, and wholesomely. I knew that I needed to return to the food community in some way to regain that connection with home cooks. Through monthly cooking classes on how to make pot stickers, soup dumplings, and simple stir-fries, the path back into the conversation opened up again.

My ultimate goal is to get you into the kitchen. Chinese cooking can be daunting because the ingredients and methods are unfamiliar, and, if you havent experienced the diversity of regional Chinese dishes, your palate may not have a baseline for the flavor profiles. The complaints I hear most often about why people dont cook Chinese food are that the ingredients seem too exotic and that cutting all the ingredients is so much work. The most common aha I hear after students attend a class, however, is that a given dish wasnt as hard to cook as they thought. Even one of my chef colleagues at the cooking school, for example, commented that she was surprised at how accessibleand deliciousmany of my recipes are. I think our brains are wired to associate long lists of ingredients with a higher degree of difficulty, causing us to see a greater challenge than exists. I make it a point to remind all the home cooks I meet to have a growth mind-set: You will likely have some mess ups to start, and thats okay. You will improve only if you first develop a