Gold Mountain Turned to Dust

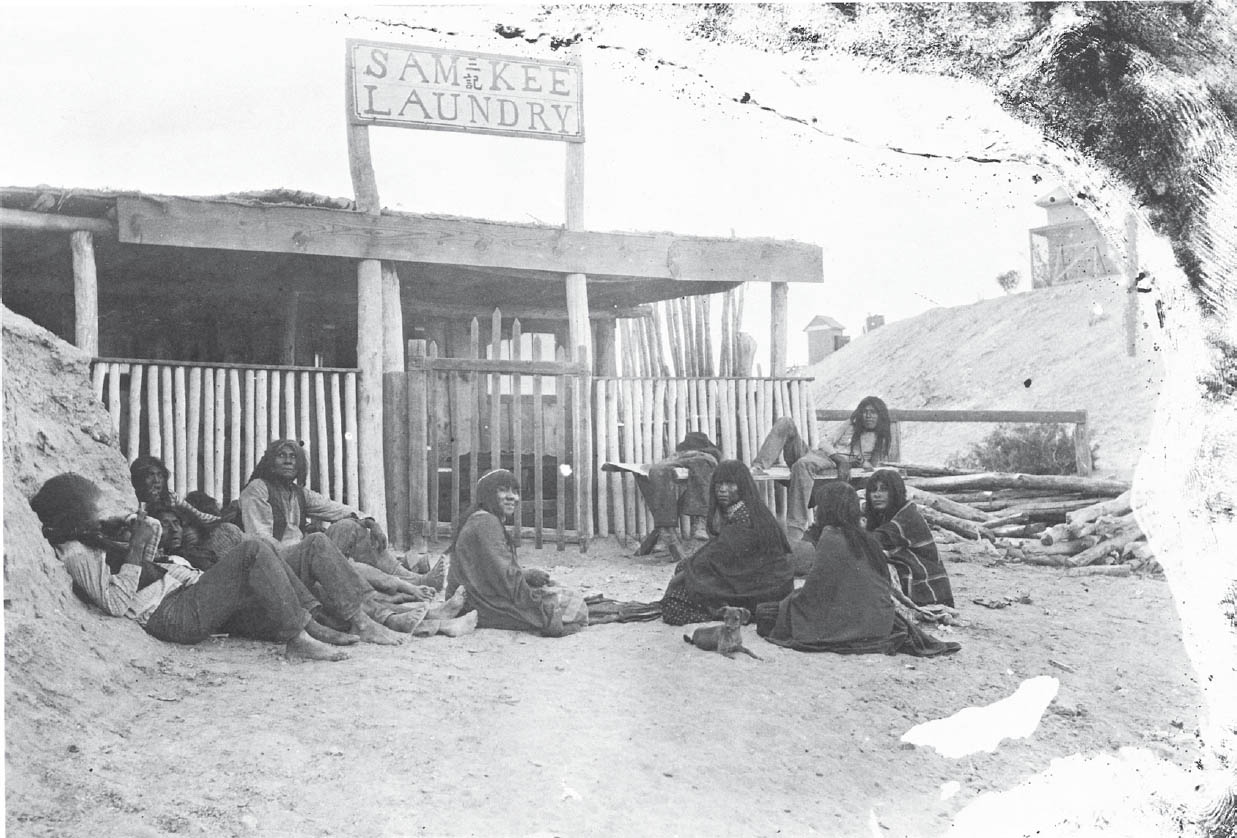

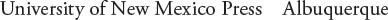

Frontispiece. Mohave Indians in front of Sam Kee Laundry, Yuma, Arizona Territory, ca. 1890. Reynolds Collection, Arizona Historical Society Library, Tucson.

Gold Mountain Turned to Dust

ESSAYS ON THE LEGAL HISTORY OF THE CHINESE

IN THE NINETEENTH-CENTURY AMERICAN WEST

John R. Wunder

FOREWORD BY Liping Zhu

2018 by the University of New Mexico Press

All rights reserved. Published 2018

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Wunder, John R., author. | Zhu, Liping, writer of foreword.

Title: Gold mountain turned to dust: essays on the legal history of the Chinese in the nineteenth-century American West / John R. Wunder; foreword by Liping Zhu.

Description: Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2018016226 (print) | LCCN 2018017102 (e-book) | ISBN 9780826359391 (e-book) | ISBN 9780826359384 (pbk.: alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Chinese AmericansLegal status, laws, etc.West (US)History19th century. | LawWest (US)History.

Classification: LCC KF4757.5.C47 (e-book) | LCC KF4757.5.C47 W86 2018 (print) | DDC 342.7308/73dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018016226

Cover illustration courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-27755

Designed by Felicia Cedillos

Original publication information is provided for the essays in this collection at the beginning of each essays Notes section.

For Susan

CONTENTS

Liping Zhu

FOREWORD

No Equal Justice for Chinese

Since the founding of the republic, Americans have been fiercely engaged in a political and ideological debate over the idea of equal rights. This continuous discourse, sometimes manifested in very violent ways, helps to define our nation. To fight for every person and group in search of equality is a never-ending task as well as a paramount mission of the country. In its long, difficult journey of making a more tolerant and inclusive society, however, the United States has suffered many setbacks and overcome many obstacles. In the second half of the nineteenth century, the Chinese, then a group of new Asian immigrants, suddenly took center stage in this fundamental American struggle. Numerous occurrences of unfair treatment of these immigrants and their resistance to injustice were an inseparable part of the larger national experience.

In the final conquest of the nineteenth-century trans-Mississippi West, the Chinese played a dual role of victor and victim. During that period about half a million Chinese arrived in the United States, most of them residing in the West. Their exceptional contributions to major economic spheres, such as gold mining, railroad construction, and land reclamation, were crucial to the speedy settlement of the region. The Chinese, like many other unwelcome groups, also became a target of systematic political discrimination and widespread racial violence. In any ethnic subjugation throughout history, legal mistreatment and physical attack have often gone hand in hand. In learning about the sorrowful experience of early Chinese immigrants, however, more research has been done on ethnic violence than on biased jurisprudence. John Wunder belongs to a very elite circle of scholars who have proper training in both history and law. Such a special educational background allows him to pursue his interest in the legal history of the Chinese in the nineteenth-century American West. He has devoted much of his academic life to this field and become a revered expert. This book properly caps his successful scholarly career.

In addition to such notability, John Wunders work also demonstrates a lifelong journey of intellectual inquiry into the relationship between American laws and Chinese immigrants. In the mid-1970s, Wunder, an ambitious young historian, was contemplating producing, in timely fashion, a comprehensive legal history of Chinese immigrants in the nineteenth-century American West. He soon realized that producing such a monograph was not feasible because of the enormous number of trial-case files scattered across the West. It might take many years to amass all the necessary materials. However, this logistical hurdle didnt diminish his enthusiasm for the study. Taking a more manageable case-study approach, he decided to write a single essay at a time, focusing on a small area or region. In the following forty-plus years, Wunder published, in addition to many other works, eight single-authored articles and one coauthored article on the subject. To cap his extraordinary scholarship in the study of western legal history, Wunder has now gathered all nine articles, plus a new piece, into this single volume. Amazingly, these ten separately written essays cover almost the entire American West, from California to Montana and Washington to New Mexico. The broad geographical scope of these studies indicates that Wunder, despite at first doubting the feasibility, eventually visited all the archives necessary to complete his grand project. This four-decade-long circuit ride also helped Wunder to find many unrelated local cases that shared either common political themes or legal doctrines.

Although Gold Mountain Turned to Dust is not exactly the kind of book Wunder envisioned forty years ago, this collection of conceivably connected and mutually supportive articles does meet the original goal of furnishing a basic text on the legal treatment of Chinese immigrants in the West. As in most anthologies, the essay-chapters are arranged according to their scope and focus, moving from general to specific. The first two essays deal with a pair of intertwined themes regarding the mistreatment of Chinese immigrants: racial violence and judicial discrimination, serving as a broad introduction to the book. Especially the leading chapter, Anti-Chinese Violence in the American West, 18501910, a quarter-century-old classic, remains as the first source to be consulted by anyone who wants to learn about anti-Chinese violence. The following eight pieces each examine legal precedents or judicial doctrines derived from these Chinese cases, which greatly complicated the western legal system.

No case involving Chinese immigrants is more discussed than People v. Hall (1854). What it did to the Chinese is equivalent to what the Dred Scott decision (1857) did to African Americans. In 1853, three white miners, including George Hall, robbed and murdered a Chinese miner in Nevada County, California. At the trial, both Chinese and white witnesses were called. The jury quickly convicted Hall and sentenced him to death. The defendant then appealed to the California Supreme Court on the grounds that he was convicted of murder upon the testimony of Chinese witnesses. At that time, California statutes prohibited only Indians and blacks from testifying against a white man. Introducing ingenious concepts of racial categorizing, the justices argued that since Chinese immigrants and Native Americans had the same Asian ancestors, the Chinese, of course, should not be allowed to possess the legal privilege to testify against whites. Therefore, the state supreme court reversed the lower courts verdict and set Hall free. By crafting such a precedent, denying Chinese the right to testify in both civil and criminal proceedings, the ruling had an extremely deleterious impact on the life of Chinese immigrants in Californiait made it more difficult to bring white perpetrators to justice. This case was directly responsible for many subsequent anti-Chinese violent acts. Despite the modest title,

Next page