Contents

Guide

Page List

THE

Chinese

Question

The Gold Rushes and Global Politics

MAE NGAI

F OR F ELIX

What is the matter with foreignness?

TONI MORRISON

Contents

Illustrations follow .

World Gold Production and Discoveries

Map by Cailin Hong

The Asia-Pacific

Map by Cailin Hong

China, Emigration Sending Regions, 18501910

Northern China

Map by Cailin Hong

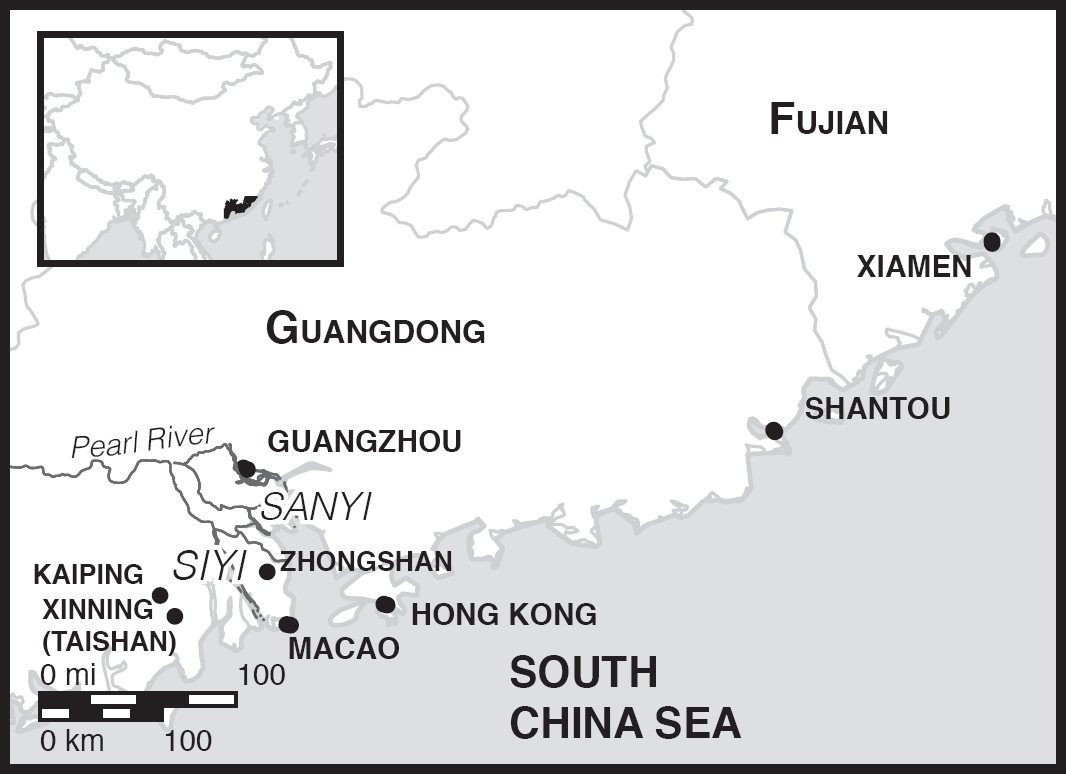

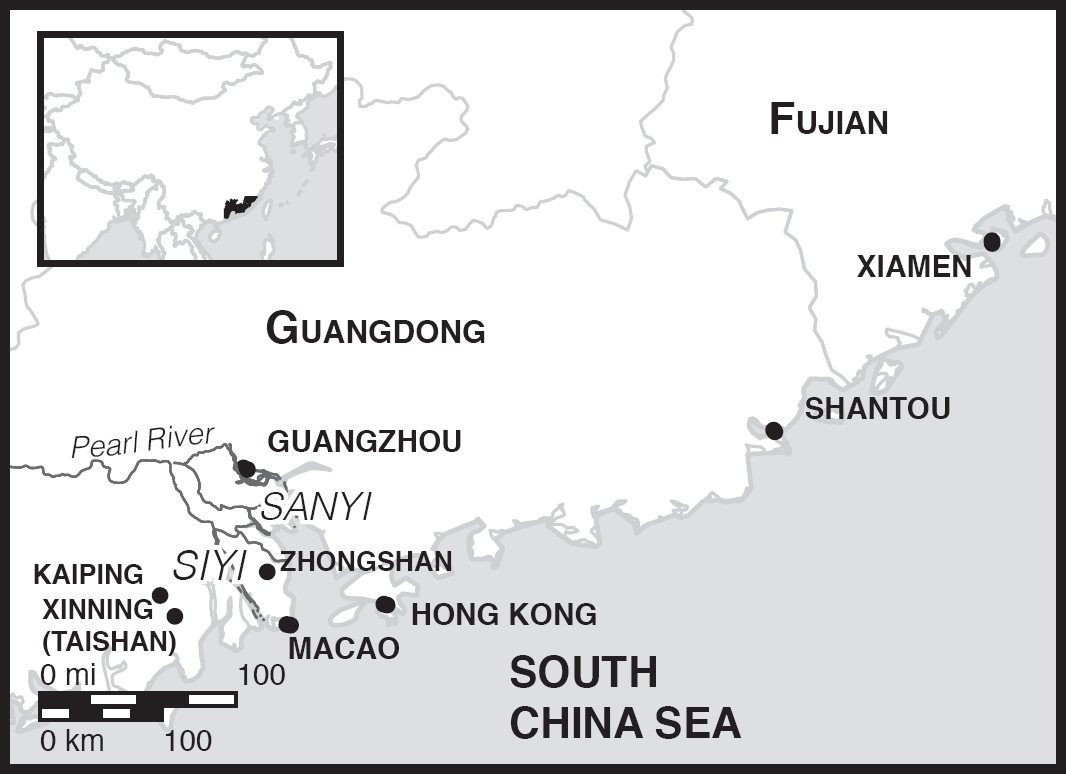

Southern China

Map by Cailin Hong

Chinese proper names are given in pinyin with surname first, e.g., Yuan Sheng. In cases where individuals and organizations were known by their names in Cantonese transliterations or other romanization systems, the pinyin is provided in parentheses, if known, e.g., Lowe Kong Meng (Liu Guangming). Many ordinary Chinese people appear in Western records only by a familiar form of address, e.g., Ah Bu, with no indication of their full Chinese name.

Chinese place names are rendered in pinyin with the old Anglicized name in parentheses, e.g., Guangzhou (Canton), Xiamen (Amoy), Yantai (Chefoo), unless commonly known otherwise, e.g., Hong Kong. A glossary of Chinese proper names with pinyin, Cantonese, and Chinese characters may be found on .

Currencies used in this book include the Chinese silver tael and yuan (dollar), the British pound sterling, the Mexican silver dollar, and the U.S. dollar. The value of taels varied by location in China. In 1875 the Imperial Maritime Customs Office introduced the Haikwan (haiguan) tael (HKT), or customs tael, an abstract measure used in official trade accounts. One HKT was the equivalent of 1.25 troy ounce of silver.

During most of the period covered in this book, 1 = 3.45 taels = $4.80. One Mexican silver dollar = 0.72 tael. The U.S. dollar was roughly equivalent to the Mexican silver dollar. In 1899 the Qing introduced the Chinese yuan (dollar) on par with the Mexican dollar.

The price of gold remained stable throughout the nineteenth century to World War I, with one troy ounce of gold = 3 17s.10d. = $20.67. Until the 1870s the silver-to-gold ratio was between 12:1 and 15:1. In the late nineteenth century, the gold-price of silver fell from 58d. per ounce in 1875 to 37.5d. in 1892 and to 27d. in 1899, a depreciation of more than 50 percent. The value of one HKT fell from six shillings in 1875 to two to three shillings in 19005. In 1905 one Mexican/U.S./Chinese dollar was about 27 pence, or slightly more than two shillings.

Mountains of gold towered on high,

Which men could grab with their hands left and right.

Eureka! They return with a load full of gold,

All bragging this land is paradise.

G old seekers from all over the world wrote tales of the nineteenth-century gold rushes, their imagery of riches and glory even grander when rendered in verse. These particular lines are from a long poem written in classical Chinese by Huang Zunxian, a Chinese scholar and diplomat. Huang served as general consul for the Qing government in San Francisco in the early 1880s, during the time of the great anti-Chinese agitation and the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act. He was a reform-minded official who believed the United States was the most advanced nation in the world that held many lessons for the modernization of China. But while in America, Huang could not believe the oppression and violence meted out against the Chinese. He worked tirelessly on behalf of the emigrants, offering comfort to those who came to him and appealing to American officials for justice and fairness. Disillusioned and exhausted, Huang left the United States after three years. His poem, Expulsion of the Immigrants, expressed his disappointment at Americans betrayal of principles laid down by their nations founders, where all kinds of foreigners and immigrants,/ Are allowed to settle in these new lands.

The consuls view from California extended to an understanding of the global consequences of the gold rushes:

Heaven and earth are suddenly narrow, confining;

Men and demons chew and devour each other.

Great China and the race of Han

Have now become a joke to the other races.

He wondered, too, whether other countries would follow the American example of Chinese exclusion: Within the vastness of the six directions, / Where can our people find asylum?

THIS BOOK EXPLORES the origins of Chinese communities in the Anglo-American world, locating their beginnings in the three largest gold-producing regions of the nineteenth century: California, Australia, and South Africa. It is a story about Chinese emigrants dreams, labors, and communities, as well as their disappointments and sufferings, and their fateful marginalization and exclusion from self-described, self-anointed white mens countries. It is the story about the making of the Chinese diaspora in the Anglo-American world during a tumultuous period in world history, during which gold fever and racial politics marked the closing of frontiers in the United States and in the British Empire; a time that saw the ascendance of British and American financial power and the inclusion of China in the worlds family of nations, but as an unequal and marginal player. It reveals that Chinese exclusion was not extraneous to the emergent global capitalist economy but an integral part of it. The Chinese Question is the story of how the Chinese communities in the West were born of a powerful alchemy of race and moneycolored labor and capitalism, colonialism and financial poweracross the nineteenth-century world.

THE CHINESE WHO WENT to the gold rushes were part of an expanding population of Chinese living abroad in the nineteenth century. Since at least the thirteenth century of the Common Era, people from Chinas southeastern coastal provinces had traded in Southeast Asia, from Indonesia and the Philippines to Vietnam and the Malay Peninsula to Thailand. But in the nineteenth century they traveled much farther from home, spurred by both need and opportunity. A quarter-million Chinese went as indentured laborers to European plantation colonies in the Caribbean as part of the notorious coolie trade that exploited Chinese and Indian workers after the abolition of slavery.

An even greater number of Chinese, more than 300,000, went as voluntary emigrants to the United States and to British settler colonies in the nineteenth century, attracted first by the gold rushes. The Chinese gold seekers were not, of course, the first to cross the great oceanthat distinction is held by the Polynesian peoples whose seaborne migrations began over one thousand years BCE. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Spanish ran a yearly galleon trade between Acapulco and Manila, the long middle leg of a journey that traded New World silver to China for silks, porcelain, and other luxuries for Europe. By the early nineteenth century, a budding U.S.-China trade of northwestern American furs and pelts and Hawaiian sandalwood drew new routes across the ocean.