Copyright 2010 by Mae Ngai

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

www.hmhco.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Ngai, Mae M.

The lucky ones : one family and the extraordinary invention of Chinese America / Mae M. Ngai.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-618-65116-0

1. Tape family. 2. Chinese AmericansCaliforniaSan FranciscoBiography. 3. Chinese AmericansCaliforniaSan FranciscoHistory 19th century. 4. Chinese AmericansCaliforniaSan FranciscoHistory 20th century. 5. Chinese AmericansCaliforniaSan FranciscoSocial conditions 19th century. 6. Chinese AmericansCaliforniaSan FranciscoSocial conditions20th century. 7. Chinese AmericansCaliforniaSan Francisco Cultural assimilation. 8. Chinese AmericansCaliforniaSan FranciscoEthnic identity. 9. San Francisco (Calif.)Biography. I. Title.

F 869. S 39 C 555 2010

305.895'1073079461dc22

2010 005750

e ISBN 978-0-547-50428-5

v4.0216

A portion of this book previously appeared in different form as History as Law and Life: Tape v. Hurley and the Origins of the Chinese American Middle Class, in Chinese Americans and the Politics of Race and Culture, edited by Sucheng Chan and Madeline Y. Hsu, Temple University Press, 2008.

For my Ahee

Authors Note

This book began with a surprise.

More than ten years ago, in the reading room of the National Archives, just outside Washington, D.C., I was working on my first book, a history of illegal immigration, reading documents from the U.S. Department of Labor. I came across a lengthy report, written in 1915, about Chinese who worked as interpreters for the U.S. Bureau of Immigration. A name caught my eye: Frank Tape. I recognized Tapewhich is not a Chinese surnameas the name of the plaintiff in one of the first Chinese American civil rights cases, Tape v. Hurley (1885), which forced San Francisco to admit Chinese children to its public schools. Was there a connection?

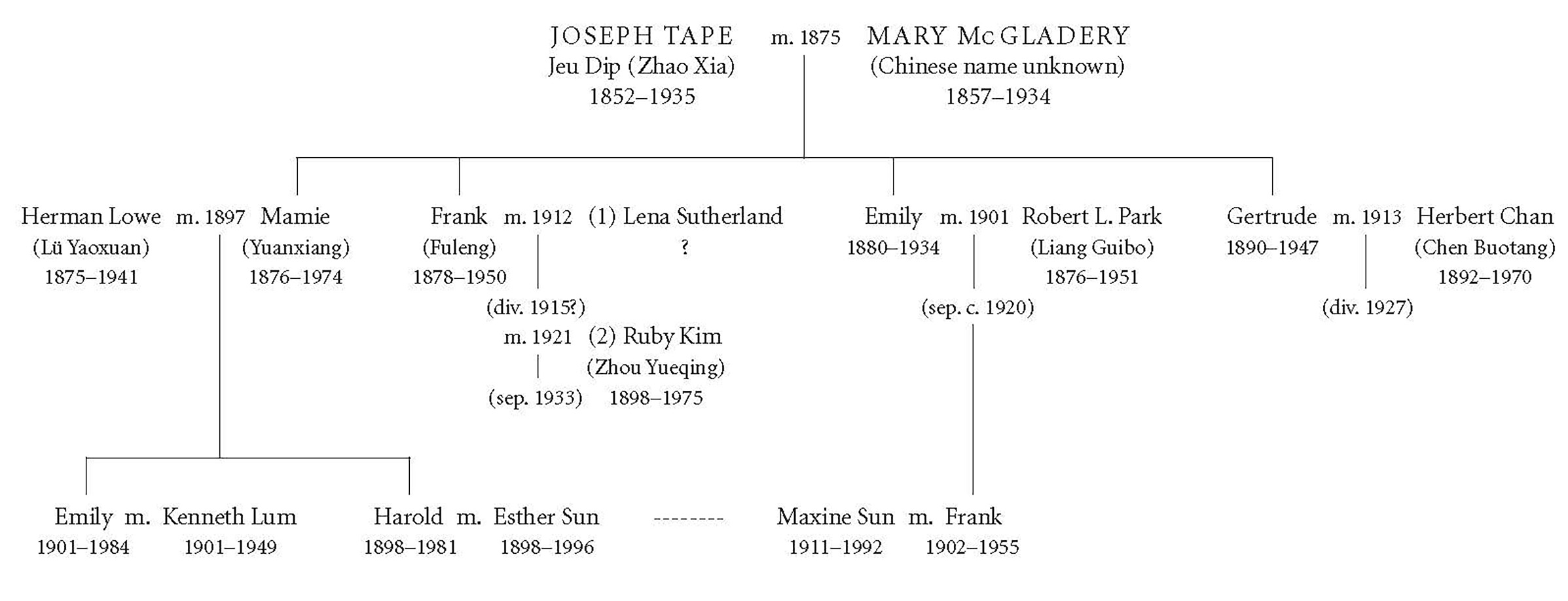

A little digging in the census manuscripts confirmed my hunch that Frank Tape was the brother of Mamie Tape, the girl who had challenged San Franciscos policy of exclusion. Curious, I dug further. Not only was Frank Tape an interpreter, but Mamie married a Chinese interpreter, as did her sister, Emily. Their father, Joseph Tape (whose Chinese name was Jeu Dip in Cantonese, or Zhao Xia in Mandarin), was an immigration broker who worked for the steamship and railroad companies in San Francisco. Their mother, Mary Tape, rescued as a young girl from prostitution by missionaries, was a painter and photographer. Although the Tapes were not formally schooled, they rose very quickly in America. They lived in white neighborhoods and were highly acculturated. Contemporaries called them Americanized Chinese. Their middle-class arrival storyincluding touring cars, hunting dogs, a family compound in Berkeley, California, and society weddingswas a revelation: Asian American history has focused on laboring people, and before becoming a historian, I worked as a union organizer. I realized how little we know about the origins of the Chinese American middle class.

There was also a puzzle: if Mamie Tape had been a civil rights pioneer, how could I understand her brother, Frank, who was accused thirty years later of extorting money from Chinese in immigration casesof profiting from the very exclusion laws his sister had protestedand then, ten years after that, was acclaimed as the first Chinese American to serve on a jury in San Francisco? How to make sense of these twists and turns?

More digging, more puzzling. In ten years of researching this book, I found out ever more about this one family and about the birth of Chinese America that fascinated and surprised. Living in the era of Chinese exclusion (18821943)that long-standing legal bar against virtually all Chinese immigration to the United Statesthe Tapes were in-betweens and go-betweens, individuals who found in their bilingualism and biculturalism opportunities for economic and social advancement. As brokers, they were at once powerful and marginal: Chinese immigrants both esteemed and resented them; their white American employers needed but didnt trust them. The Tapes were highly unusual, unlike the vast majority of Chinese immigrants in the United States, but they were archetypal members of the first Chinese American middle class. And in many ways, their story echoes the history of other immigrant groups in the United States, regardless of whence they came, for whom brokering was a common entrepreneurial strategy for getting ahead.

Unlike many books about Chinese American families, The Lucky Ones is neither fiction nor memoir, but a work of history. Researching the Tapes posed some special challenges, as they did not leave letters, diaries, or other personal papers, which biographers typically use to reconstruct the lives of their subjects. They did, however, leave to their descendants a number of photograph albums. I am grateful to Jack Kim and Linda Doler for granting me access to these albums, which provided biographical data and a sense of the texture of the Tapes lives. Many of the photographs, especially the few but remarkable ones composed by Mary Tape, tell revealing and compelling stories.

Because the Tapes were semipublic figures, their activities sometimes warranted comment in newspaper and magazine articles. Members of the family who were employed by the government appear in official records. Genealogical research has become easier with the online availability of federal census manuscripts (to 1930), military registration and enlistment records, and other vital data. These proved enormously helpful, as did court records, the Sanborn fire insurance maps, published and unpublished government reports, materials in local historical societies, and interviews conducted with Mamie Tape Lowe, Emily Lowe Lum, and Ruby Kim Tape in the 1970s.

At times, the sources were contradictory or suspect; often they were simply lacking. In writing this book, I made up nothing. But I had to interpret the material and address the problems in that material by corroborating details in multiple sources and by using reasoned conjecture to fill in gaps in the evidence. I have elaborated on the thinking that went into my interpretations in the notes at the end of the book.

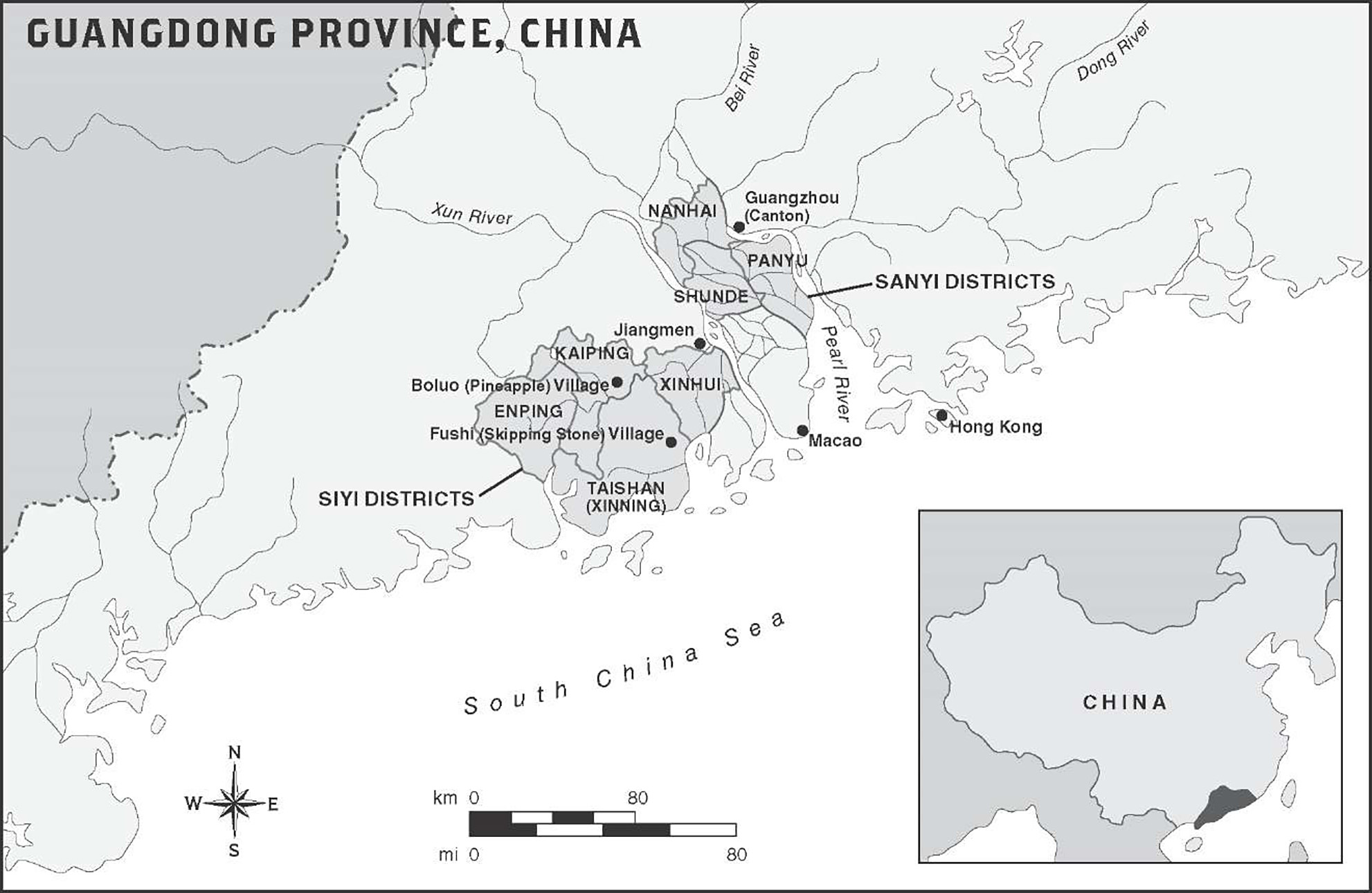

Chinese proper names appear in Chinese style, with the surname first. Chinese immigrants in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries came mostly from Guangdong Province, and thus the Cantonese pronunciations of most proper names were more common than the Mandarin. For that reason, on the first appearance in this book, proper names are given in Cantonese with the Putonghua (Mandarin), if known, in parenthesesfor example, Jeu Dip (Zhao Xia). Chinese characters for the names of major people, places, and organizations appear in the glossary.

Tape Family Tree

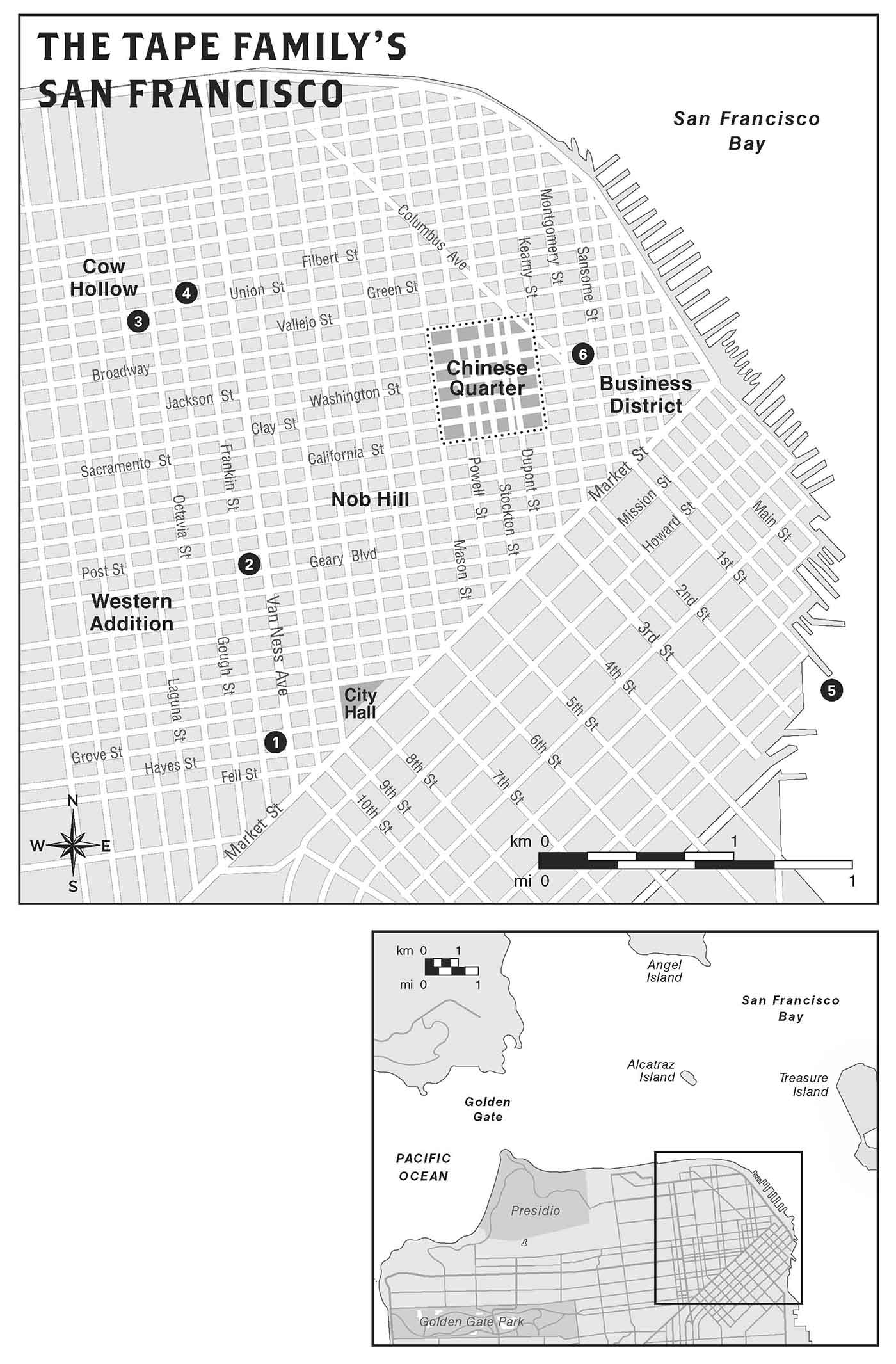

Sterling dairy ranch

Ladies Protection and Relief Society

Tape home (18761891)

Spring Valley School

Pacific Mail Steamship dock

Next page