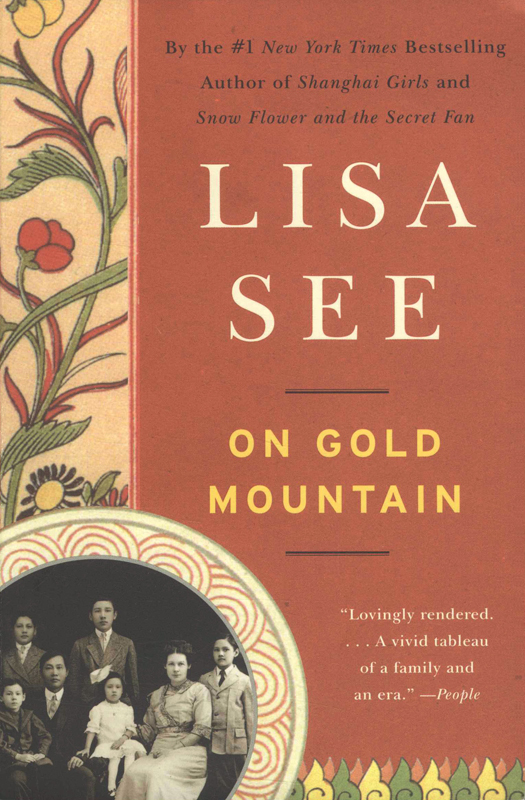

ACCLAIM FOR LISA SEEs:

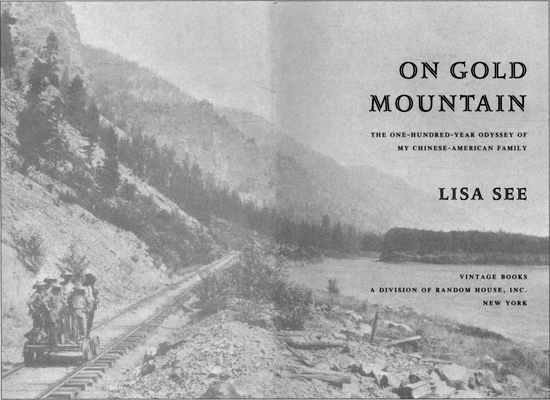

ON GOLD MOUNTAIN

Both serious social history and one familys version of realizing the California dream. Fascinating.

Seattle Times

[See] proves to be a clever, conscientious, fair-minded biographer. [She] has done a gallant job of fashioning anecdote, fable and fact into an engaging account.

The New York Times Book Review

A matchless portrait not only of a remarkable family but of a centurys changing attitudes. The ambitions, fears, loves, and sorrows of Sees huge cast are set forth with the storytelling skills of a novelist.

Publishers Weekly

Particular in its vivid characters, epic in its sweeping scope compassionate and perceptive.

Michael Dorris, author of The Broken Cord

Extraordinary! Every sentence pulsates with humor, muscle, meaning, and cool snappy music. Wonderful.

Belle Yang, author of The Lost World of Baba: A Return to China Upon the Shoulders of My Father

FIRST VINTAGE BOOKS EDITION, SEPTEMBER 1996

Copyright 1995, 2012 by Lisa See

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover by St. Martins Press, New York, in 1995.

Photo credits: Title-page spread, Asian American Studies Library, University of California at Berkeley, and , Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

See, Lisa.

On Gold Mountain/by Lisa See1st Vintage Books ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-307-95039-0

eBook ISBN: 978-1-101-91008-5

1. See, LisaFamily.

2. Seay Family.

3. Chinese Americans-CaliforniaBiography.

4. CaliforniaBiography. I. Title.

F870.C5S44 1996

929.20899510795dc20 96-11821

www.vintagebooks.com

Cover design: Chin-Yee Lai

Cover photograph: Courtesy of author

v3.1_r1

Fooling around in the papers my grandparents, especially my grandmother, left behind, I get glimpses of lives close to mine, related to mine in ways I recognize but dont completely comprehend. Id like to live in their clothes a while.

Wallace Stegner, Angle of Repose

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

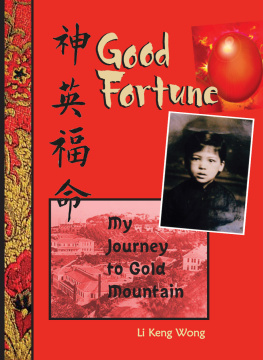

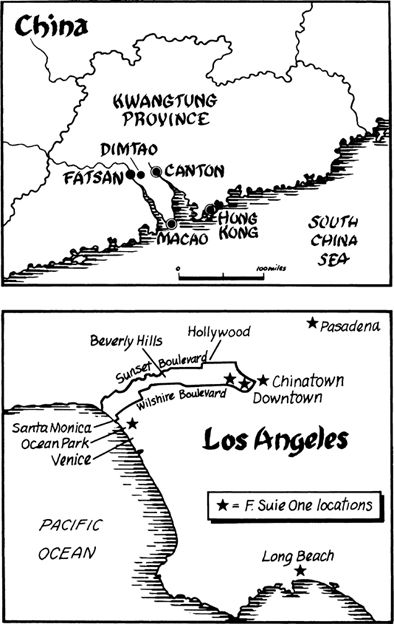

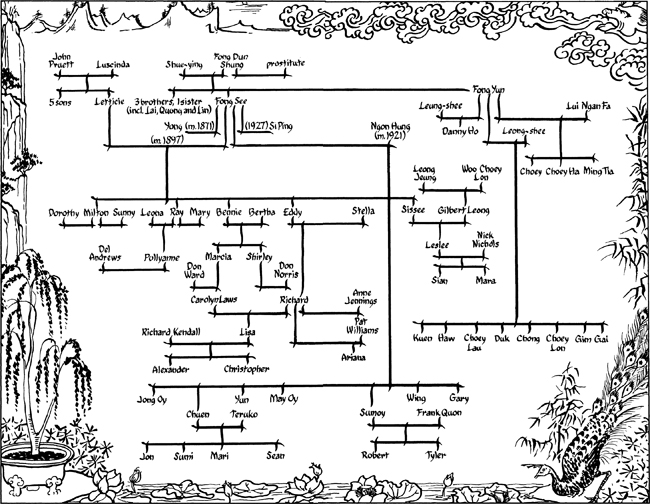

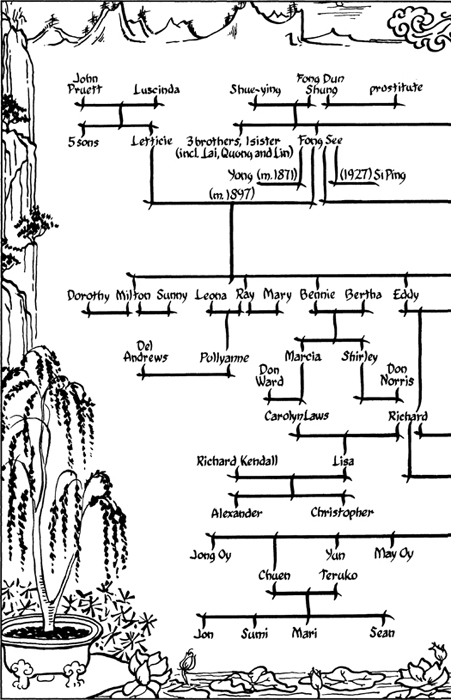

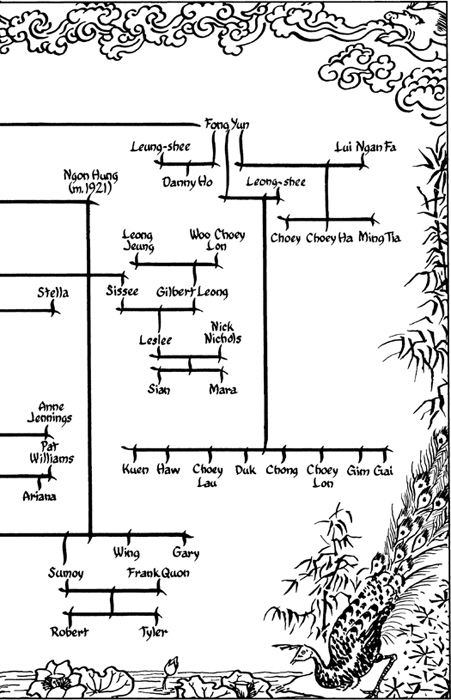

F ong See, my great-grandfather, left China in 1871 as a youngster, found prosperity on the Gold Mountain (the Chinese name for the United States), and lived to reach his hundredth birthday. Rising out of a mass of nameless Asian immigrants, he became one of the richest and most prominent Chinese in the country. He lured customers into his Asian art store by selling tickets to see a stuffed mermaid. He loved money, and had a childlike enthusiasm for fancy cars. He also had a way with women. My family always knew that Fong See had two wives. The marriage between Fong See and Letticie Pruettmy Caucasian great-grandmotherwould go on to establish the See name. The second wife, a Chinese waif who had supported herself making firecrackers, was only sixteen when she married my great-grandfather, who was sixty-four at the time. This family always lived under the name of Fong. Altogether, Fong See sired twelve childrenfive Eurasian, seven Chinesethe last born when he was in his late eighties. This is the story of the Sees and the Fongs and how they assimilated into America.

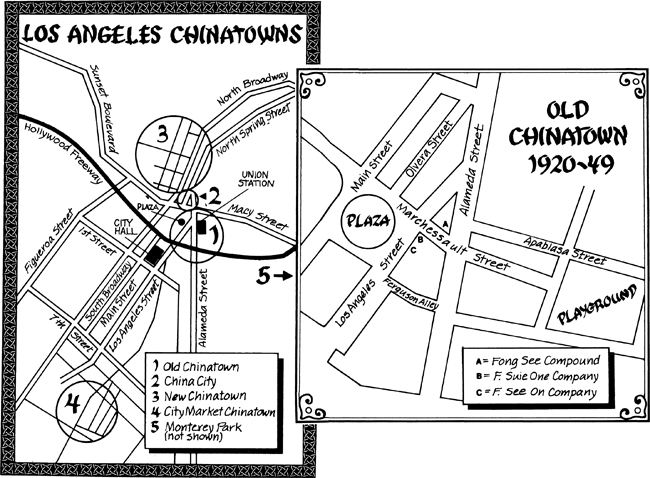

As a girl, I spent frequent weekends and most of my summer vacations with my paternal grandparents in Chinatown. We would pass through a moon gate guarded by two huge stone lions and enter the dark, cool recesses of our familys Chinese antique store, the F. Suie One Company, a gigantic mercantile museum that contained, among other things, porcelains taken from the royal kiln and floated downriver on sampans; altars pillaged from provincial temples; and huge architectural carvings shipped in sections to be reconstructed by Fong Sees sons in one of his many warehouses.

At lunchtime, Grandma Stella and I would walk up the street to a restaurant that must have had a real name but that we just called the little place. Along the way wed stop to chat with Blackie at the Sam Sing Butcher Shop, with its gold-leafed roast pig in the window. Wed stop in at Margarets International Grocery and browse through the aisles with their salted plums, dried squid, and fermented tofu. At the restaurant, wed go back to the kitchen to chat with the cook and watch as he packed up our order into cartons.

Once back at the store, Id go upstairs to the workroom, with its huge machinery and its pinups of sedate Chinese maidens, where my grandfather and great-uncle Bennie would be engulfed by dense clouds of sawdust and the din of saws. Bennie would invariably look at me wild-eyed and shout, Im gonna put you in trash can. Terrified, Id scramble back downstairs and my grandfather and uncle would wash up with Lava soap.

After lunch, if I got boredperhaps after playing in the mountains of straw packing, or climbing into the arms of a gigantic Buddha, or making a fort underneath one of the large altarsGrandma Stella would let me help her while she worked on the restoration of a coromandel screen. I might clean brushes or mix ink; sometimes she let me use my fingertips to press clay into the chipped areas. Or I might help my great-aunt Sissee as she dusted and polished her way from the bronze room to the art room to the room for scrolls and fabrics, and from one end of the main hallwhich held exquisitely carved furnitureto the other.

In the late afternoons, my grandmother and great-aunt Sissee would relax in wicker chairs in the back of the store over cups of strong tea. During that quiet and comfortable time they would reminisce about the past. They told intriguing and often silly stories about missionaries, prostitutes, tong wars, the all-girl drum corps, and the all-Chinese baseball team. They spoke about how the family had triumphed over racist laws and discrimination. Then, as inevitably as Uncle Bennies threat of the trash can, would come my grandmothers assertion that, Yes, during the war, the lo fan (white people) made all of us Chinese wear buttons so that they would know we werent Japanese.

My grandmother taught me how to wash the rice until the water ran clear, thenwithout the aid of a measuring cuppour water over the grains in the steamer up to the first knuckle of a hand. It didnt matter if it was her knuckle or mine, she explained; for five thousand years the system had worked perfectly. Finally she would place a few lengths of