For over two decades I have been intrigued by the stories of people of mixed MoriChinese heritage. When I conducted oral history research on the New Zealand Chinese I came across their family papers, official documents and photos which provided a rich background to contextualise their family stories. Various anecdotes on some local MoriChinese were tantalising. They were often mentioned tangentially.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Mori and Chinese shared the same marginalised socioeconomic position. There was much interaction between the two peoples, and the relationships were often close they were friends, neighbours and relatives. The MoriChinese story has been an unexplored part of the bigger New Zealand Chinese story. Mixed blood MoriChinese people living among the more conservative Chinese communities often met with discrimination because only pure Chinese were considered good enough.

What spurred me on to serious thoughts of conducting proper, in-depth research on MoriChinese relationships was an unsolicited letter sent to me in 1994 from a stranger who identified himself as a member of an East Coast iwi trust board. The mid-1990s was a time of a backlash against migrants from Asia, and it was not uncommon for me to receive hate mail. But this particular letter was different. Although the writer stated up front that he objected strongly to Asian immigration, he listed his reasons rather thoughtfully. He ended the letter by saying that he felt bad about not welcoming Chinese people in particular, because his favourite aunt was half Chinese. This letter alerted me to the new political dynamics between these two communities.

The MoriChinese stories have been largely neglected by both Mori historians and New Zealand Chinese historians, and they have hardly featured in mainstream New Zealand history. If mentioned at all, Mori Chinese were often referred to as humble market-gardening families living in poverty. Their big families had mixed parentage and little discipline, some interviewees said. Moreover, the Chinese fathers often had other wives in China and they kept separate Chinese families. Even more embarrassing was that some of the liaisons were short-term affairs where sexual favours were just traded for small sums of money, and casually.

At an early stage of this research I spent some time at the taki campus of Te Wnanga-o-Raukawa. A well-meaning elder warned me about how difficult it would be to obtain meaningful material to write MoriChinese family stories. He chose his words very carefully, and his pained expression clearly showed that he was delving into a past that he was reluctant to examine too closely:

Are you sure you wish to pursue this study on MoriChinese relations? I dont think people will tell you much. Actually, between the Chinese and the Mori, often there werent marriages as such. There were relationships, yes. After all, the Chinese men lived here without their women for years and years. But often the Mori girls wouldnt expect marriage.

Look, its not up to me to say, to criticise our old people and say that they shouldnt have sent our young women to the Chinese. I mean, those were very hard times. The girls only did as they were told. More often than not, theres no marriage, not even long-term relationships.

Given the social context of these early encounters, the elder concluded that as a group the MoriChinese would be very sensitive and unwilling to share any in-depth information.

He could have been proven right except for the amazing generosity and trust shown to me by many MoriChinese interviewees and their relatives, as well as their immediate community. Sharing memories of ones past is never easy, especially when those memories involve a struggle against social discrimination and, in many cases, family disapproval. Trying to establish a positive MoriChinese identity when both Mori and Chinese were considered undesirable must have been a continual struggle. However, I was known to the interviewees in various capacities: as a writer, a serious researcher, a community advocate; as somebody devoted to bettering race relations. There was a mutual trust which took decades to grow, and that became the foundation on which in-depth interviews could be conducted.

Of the seven families whose stories are featured in this book, I have known three of them since the 1980s the Joes (chapter 1), the Lees (chapter 4) and the Goddards (chapter 5).

Charles Joe worked at the then AIT (Auckland Institute of Technology). He came to one of my public lectures on Chinese New Zealanders and handed me his name card, which read Charles Joe, Mori Liaison Officer, AIT. Here was a man with a New Zealand Chinese name working in a Mori-liaison role for a national educational institution! I remember making a mental note of the details. In my previous research I had visited the Joe ancestral village in south China, and I also knew of many members of the clan scattered around New Zealand. I knew the Palmerston North branch (which Charless father came from) quite well because I had been asked to review a Chinese book manuscript on New Zealand Chinese history written by a Joe kinsman. Socially, I am also lucky to be rather close to various members of the MoriChinese Pukekohe families, many of whom are related to the Joes. Through various sources I learnt about the Joe family legend of the Mori matriarch having a premonition that all her daughters must marry Chinese men. Charles Joes late father was the one who married the eldest daughter when she was only seventeen.

I met Lily Lee when she was still married to ex-husband David Lee. Both are respected educationists, devoted to multiculturalism, working for the betterment of relationships between Chinese and Mori. In the early 1990s there was a special need for closer interaction between groups because some Mori leaders had become shrill critics of the new Asian immigrants. In 1994 I approached the Race Relations Office to help arrange a pan-Chinese community visit to the Ngti Whtua Marae at Orakei. Both Lily and David helped with the coordination efforts. Lily in particular gave talks to the Chinese community delegates, explained protocol and taught waiata. We have maintained a cordial friendship ever since. Lilys daughter Jenny Bol-jun Lee wrote her MA thesis on her own family stories. As the examiner of her thesis, I was very favourably impressed and also much intrigued, deciding to explore the story of the family properly if given the chance.

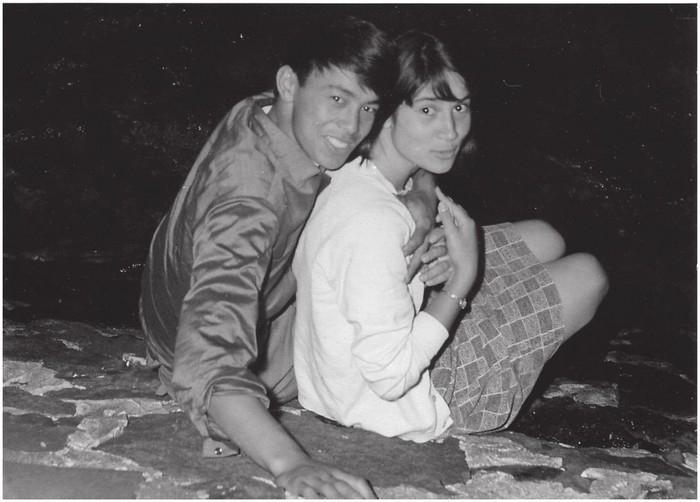

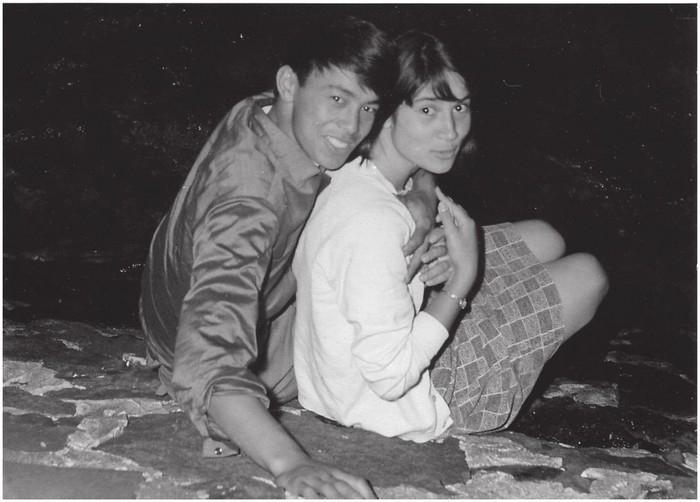

Charles and Sandra at Mission Bay, 1966, after their engagement.

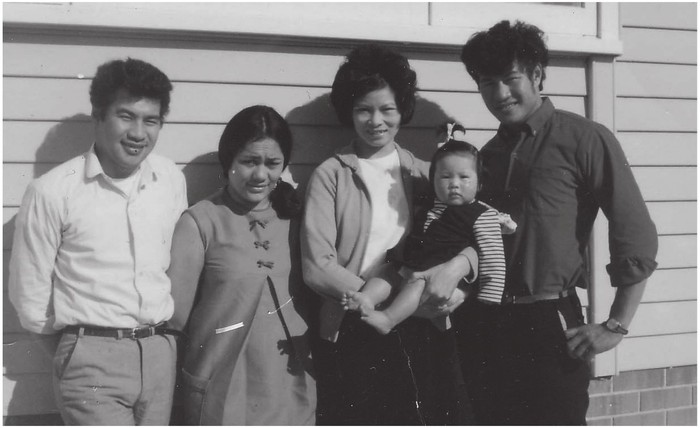

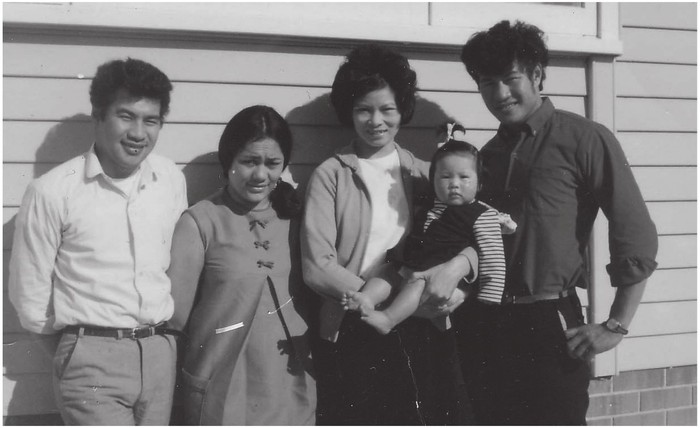

Outside the family home in Riverhead, West Auckland, 1969. Lily holding her baby Jenny, flanked by her husband Davids siblings, Bill, Mary and Danny.

With the Goddard family I knew Nancy several years before I met her son Danny, whose family story is featured in chapter 5. Nancy married George Goddard, who had a Mori, Scots, German and Jewish whakapapa. Imbued with socialist, egalitarian ideals, they were among the earliest champions of the Mori cause way back in the 1970s, long before indigenous-rights issues became fashionable among liberals. In the late 1980s, while I conducted interviews at their Evans Bay home in Wellington, quite often Mori women would drop in and stay to talk. It was obvious that they were very close to Nancy. Once they took away batches of newly baked scones for a tangi, and another time they talked at length about going to the Wellington District Court to support our Mori boys in trouble. Subsequently I found out that Nancy had worked as a Mtua Whngai Court Officer (Mori support person in the courts) for eight years. The boys she referred to turned out to be grown men who dwarfed tiny Nancy. In her presence, however, they were often subdued, shame-faced youngsters needing Aunty Nancys help.