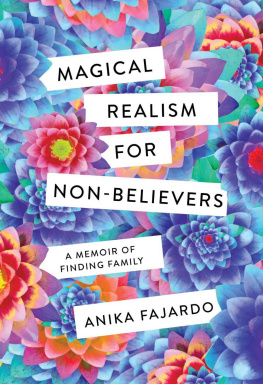

Magical Realism for Non-Believers

Magical Realism for Non-Believers

A Memoir of Finding Family

Anika Fajardo

University of Minnesota Press

Minneapolis London

Copyright 2019 by Anika Fajardo

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published by the University of Minnesota Press

111 Third Avenue South, Suite 290

Minneapolis, MN 55401-2520

http://www.upress.umn.edu

The University of Minnesota is an equal-opportunity educator and employer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Fajardo, Anika, author.

Magical realism for non-believers : a memoir of finding family / Anika Fajardo.

Minneapolis : University of Minnesota Press, [2019]

Identifiers: LCCN 2018049197 (ebook) | ISBN 978-1-4529-6062-3 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Fajardo, Anika. | Fajardo, AnikaFamily. | Colombian AmericansMinnesotaMinneapolisBiography. | Minneapolis (Minn.)Biography. | ColombiaBiography.

Classification: LCC F614.M553 (ebook) | DDC 977.6/579053dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018037433

To Dave

Contents

When I arrived in Colombia, my father hugged me and kissed me as if we had done this before, as if we were family, as if we had not been apart for a lifetime. I remember the damp night air as I stepped through the whir of automatic doors from the antiseptic white of the terminal into the suffocating heat. Santiago de Cali, the capital city of the Valle de Cauca province, is only three hundred miles from the equator, and the tropical heat caught in my throat with its sweet pungency of exotic fruits and diesel exhaust. I remember hearing my name, a shout above the chorus of gritos. I looked up and saw a face that was eerily familiar.

Even though two decades had lapsed since the pictures I had of him were taken, I could still identify this man. My father. Renzo. His black hair and mustache, now threaded with strands of gray, were recognizable from the yellowed snapshots. His high cheekbones (the ones I had inherited) looked like they must have at some point left a certain type of woman swooning. He wore thick, dark-rimmed glasses, and I suspected that the fine lines behind the lenses had come from years of winking at pretty girls. Renzo was so handsome, my mother used to gushliterally gushand I tried to see in him what she had seen. But I could only compare his seemingly instantaneous aging (that transition from a young husband in old photographs to this graying man in real life) to that of my mother, whom I had watched throughout my life, day by day, and whose soft lines and fading hair were imperceptible to me.

Hello, he said with a strong emphasis on the h as if it would get away if he didnt catch it in his mouth. He was, I should have seen then, a master of understatement, a magician with unassuming gestures and kept secrets. This greeting in English seemed somehow hollow, falling short of expectation. Where were the Spanish flourishes to mark the occasion of a father meeting his adult daughter? But maybe he didnt know what to say. What do you say to someone who is kin and yet not, who shares your DNA but about whom you know nothing? Hello was perhaps the only option.

He put his brown hand on the shoulder of a young and solid-looking woman next to him. This is my wife, Mara CeciliaCeci, he said, and I kissed them both in greeting from across the barricade before making my way around the mass of Colombians, who greeted one another with the enthusiasm and abandon that I recognized as the missing ingredient in our first exchange.

But when at last I had made it past the throngs of passengers and luggage, when no physical barrier was between us, he hugged me, squeezed me until my neck was cramped into an unnatural angle. He smelled of cigarette smoke and soap, and the wiry hairs of his mustache tickled my cheek. It felt strange to hug a man so small, no taller than my mother. When he embraced meas if physical closeness could spawn intimacyI held on, hoping and wondering if he was right.

Ceci, cute and compact in a short sundress and thong sandals, hugged me, too. Her shoulder-length hair was pulled into an unruly ponytail and outlined her smooth, brown face. In an accent so thick I almost didnt understand her, she greeted me enthusiastically in English.

As I followed this man and his wife to their car, a foreign-sounding bird cried from the trees at the edge of the parking lot. I couldnt help thinking of Macondo, the fictional village in One Hundred Years of Solitude, the town that had been formed by hacking away the vegetation of the jungle to make way for the Buenda family. I had read Gabriel Garca Mrquezs novel when I was in high school, and even while I was reading it, I had felt the weight of expectation that I should love the book because it was Colombian. Like the assumptions that I should prefer spicy foods and tan easily, it felt as if I should love everything Colombian because of my birthplace. And while I couldnt tolerate hot chilis and my shoulders did occasionally burn on bright summer days, I had wanted to love the novel simply because I had wanted Colombia to prove to me how beautiful, magical, wonderful she was, to show me why my father had chosen her over me.

You sit in front, my father said, climbing into the back of a tiny Suzuki jeep, which smelled of bananas and warm summer days. It was nine in the evening, and as Ceci honked and lurched around slow-moving cars and crowded roundabouts, I wondered if Colombia would always be for me a jostling and jerking of motion and movement, a stretching and folding of moments and minutes.

I watched childrenbarely tall enough to peek insidepester us at every red light, asking to wash the windows or sell us bags of unfamiliar fruit. I had not yet tasted the sweetness of the guyaba and guanbana and maracuy. From the car I watched a black woman in a colorful turban selling something out of a basket that rested between her ample knees. Chontaduros! she called. Later I learned that I didnt like this small, hard fruit cooked with saltnot everything in Colombia met my expectations or satisfied my palate. Young men on bicycles wove in and out among tiny cars and speeding traffic, oblivious to danger. Strung between turquoise and salmon buildings, white shirts and blue towels fluttered like flags. The lights of the houses on the hills surrounding Cali twinkled in the night and looked like stars.

When my mother first arrived in Colombia, she was nineteen, just a bit younger than I was now. I tried to imagine her seeing this place for the first time. For the tenth time. Did she get used to it? Did the things she saw eventually become just part of the landscape, or did they remain foreign? I tried to fit it all into what I had imagined, the man seated behind me into the shape of a father.

Ceci drove and gesticulated, and my father leaned between the seats. Are you hungry? he asked. Qu quieres comer?

I didnt know what I wanted to eat. I was barely off the airplane, still transitioning. My last meal had been something with rubbery chicken and atrophied mushrooms on flight 965, the same number of the American Airlines flight bound for Colombia that had, just one week earlier, landed not on the runway of the Alfonso Aragn International Airport but nose first in the mountains surrounding the city. The village of Buga was the deathbed for most of the nearly sixty people aboard the 757. My father told me later that his friend was in the village at the time and watched looters search for cash left in singed wallets and valuables hidden in dented suitcases. As news of the crash made its way around the world that day, I was in the kitchen of my mothers little bungalow in Minneapolis, the one she bought after her second divorce. I was packing for the month between college semesters that I would spend in Colombia.