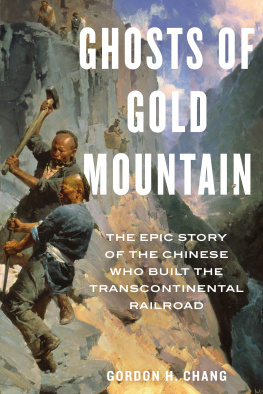

Copyright 2019 by Gordon H. Chang

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

hmhbooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Chang, Gordon H., author.

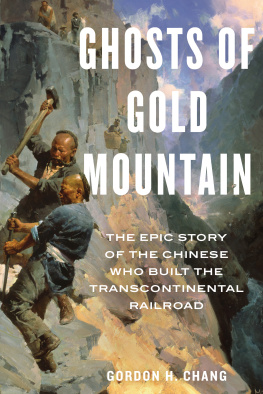

Title: Ghosts of Gold Mountain : the epic story of the Chinese who built the transcontinental railroad / Gordon H. Chang.

Description: Boston : Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018042558 (print) | LCCN 2018051358 (ebook) | ISBN 9781328618610 (ebook) | ISBN 9781328618573 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH : Central Pacific Railroad CompanyEmployeesHistory. | Railroad construction workersWest (U.S.)History19th century. |Foreign workers, ChineseWest (U.S.)History19th century. |ChinaEmigration and immigrationHistory19th century. | ChineseWest (U.S.)History19th century. | West (U.S.)History19th century.

Classification: LCC HD 8039. R 3152 (ebook) | LCC HD 8039. R 3152 C 524 2019 (print)| DDC 331.6/251097809034dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018042558

Cover design by Allison Chi

Cover image Mian Situ

Author photograph Paul Yeung, South China Morning Post

v1.0419

Maps by Mapping Specialists, Ltd.; Excerpt on from China Men by Maxine Hong Kingston. Copyright 1977, 1978, 1979, 1980 by Maxine Hong Kingston. Used by permission of Alfred. A. Knopf, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

For the forgotten

Introduction

H UNG WAH STEPPED UP INTO THE PRIVATE TRAIN CAR OF James Strobridge, the field construction boss of the Central Pacific Railroad Company (CPRR). The wagons well-appointed interior must have seemed a dark, cool oasis for the seasoned Chinese worker, offering a bit of welcome relief from both the blistering afternoon heat in the Utah desert and the bleak, monotonous scenery.

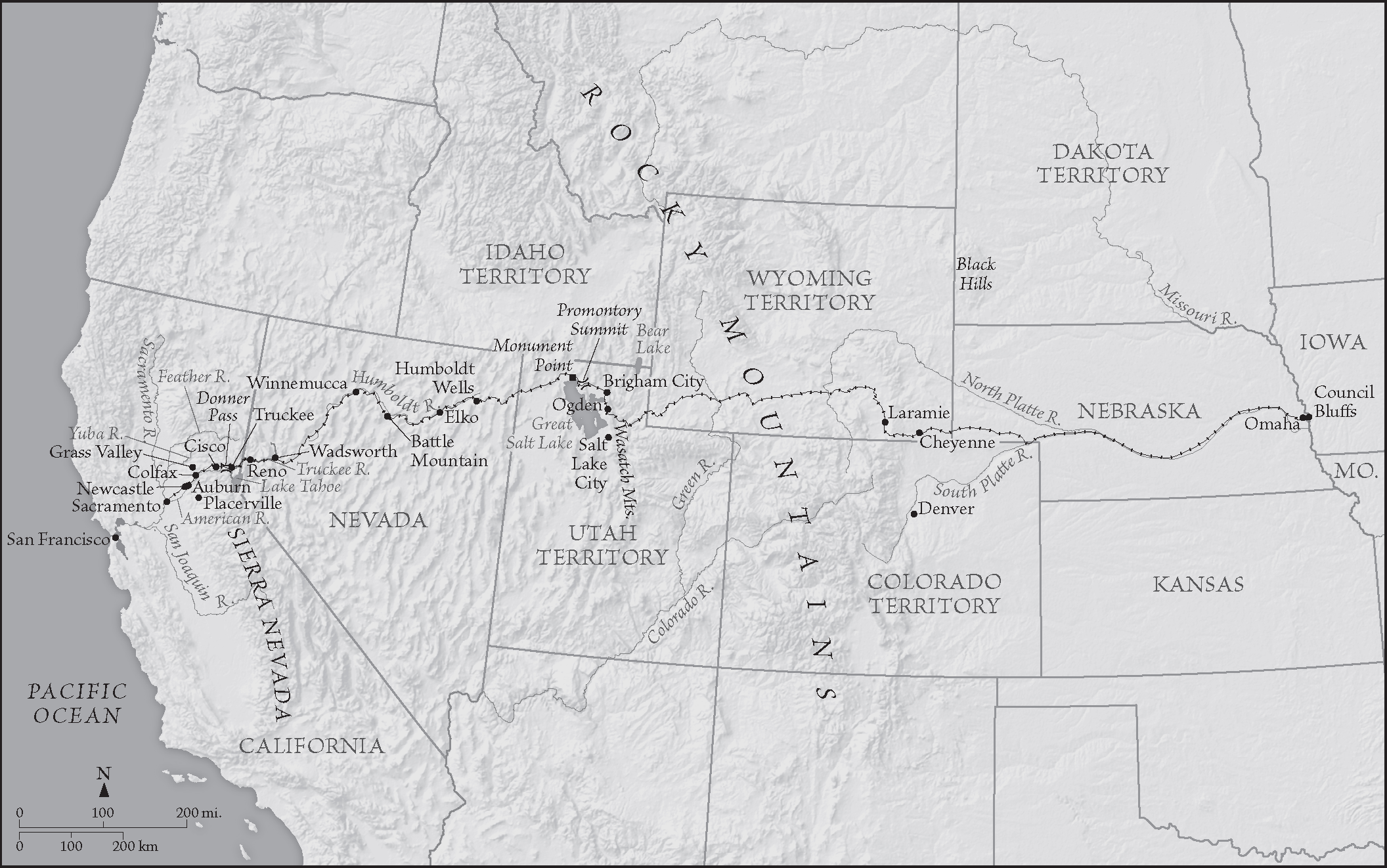

Hung Wah and Strobridge had come to know each other well over the previous five years during the construction of the Pacific Railway, or the Transcontinental Railroad, as it was popularly known. Two competing railroad companies had led the project: the CPRR, which began its work in Sacramento, California, and built eastward, and the Union Pacific (UP), which started in Omaha, Nebraska, and built westward. Their completed work, linked to already established rail lines in the East, forged a continuous road of iron across the entire country, making possible travel unprecedented in scale and speed. Now the two men were coming together at Promontory Summit, Utah, where a grand celebration had just concluded to mark the formal end of work.

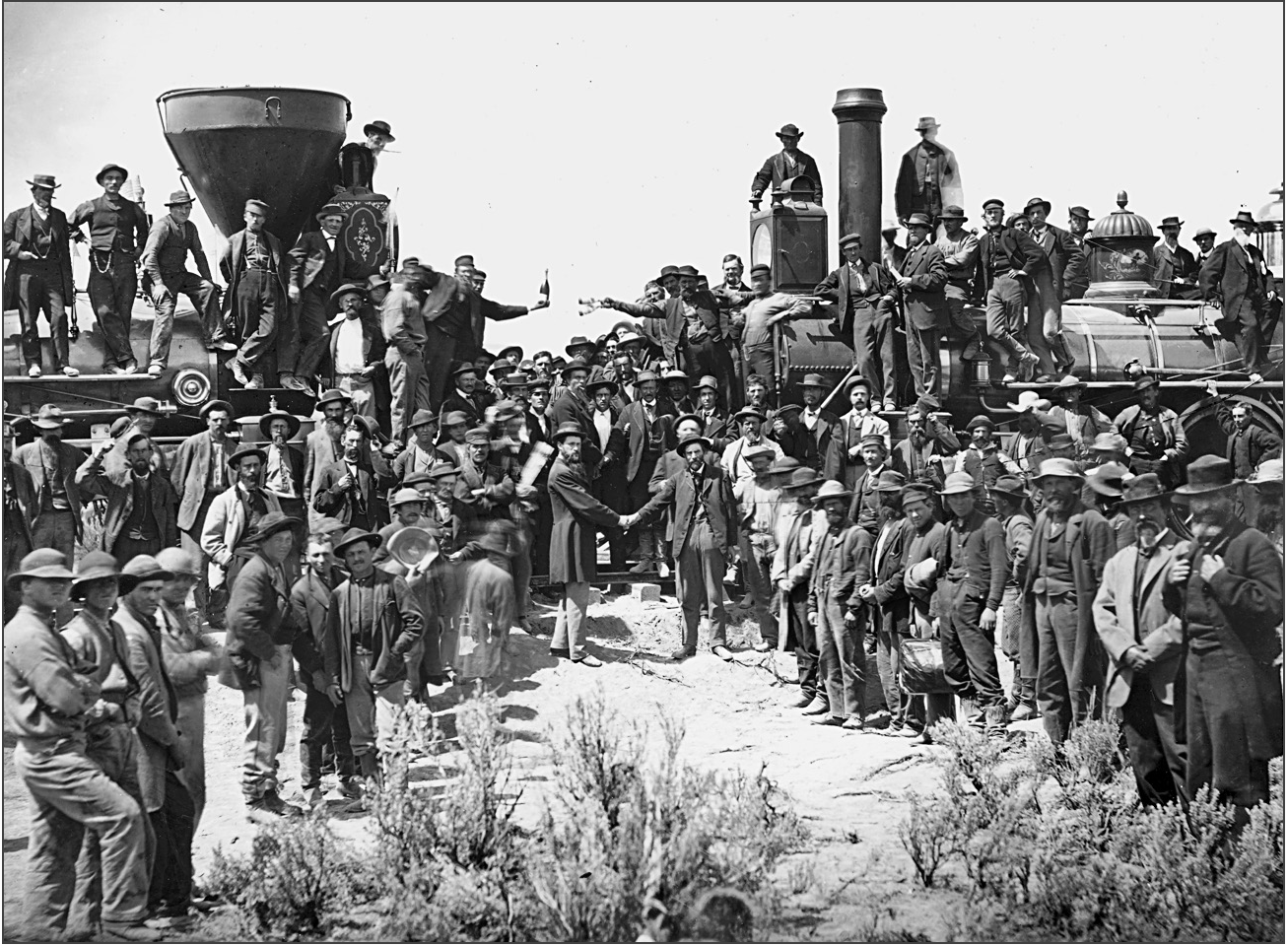

The dateMay 10, 1869has been immortalized by one of the most famous photographs of nineteenth-century America: two massive steam engines, representing the CPRR and UP, meet head-to-head in East and West Shaking Hands (below). The photographer, Andrew J. Russell, wanted to highlight the trains bonding of vast geographic space. Others at the time saw the rail connection as transformative not just for the nation but for civilization itself. Only Christopher Columbuss discovery of the New World, an energetic observer declared, surpassed the completion of the rail line in historic importance.

After the camera shots and public events, Strobridge gathered journalists, military officers, and other notables to mark the occasion in a quieter way over drinks and food in his personal railroad car. In what must have seemed a magnanimous gesture at the time, he invited Hung Wah, who brought several other Chinese with him to share the special moment, representing the thousands of Chinese who had toiled for the CPRR and made possible what many had once claimed was an insurmountable construction challenge.

Upwards of twenty thousand Chinese, 90 percent of the CPRR construction labor force, had built almost the entire western half of the Pacific Railway. The UP relied largely on Irish and other European immigrants and both black and white Civil War veterans for its labor force. While the CPRRs leg of the railway ran to a little over half the length of the Union Pacifics portion690 miles compared to 1,086building the western section posed a considerably greater challenge. The majority of the Union Pacifics line extended over relatively open, even countryside, beginning in Omaha, where the countrys existing rail network ended. The CPRR, by contrast, faced a shorter but much more arduous journey. Beginning in Sacramento, roughly at sea level, it ascended almost immediately into the foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountain range, climbing higher and higher until it reached elevations of over seven thousand feet. To reach those heights, the workers of the CPRR had to blast and dig their way through expanses of solid granite and brave some of the most dangerous working conditions imaginable. Chinese workers did what was widely considered at the time to be impossible. They endured scorching summer heat in the high altitudes, dirt and choking dust, smoke, and fumes from the constant use of explosives. They survived isolation, desiccating winds and thin air, winter blizzards and freezing temperatures, as well as the ever-present dangers of accidental explosions, falling trees, snowslides, avalanches, cave-ins, illness, broken limbs, and plain exhaustionall to realize the federal governments great ambition of uniting the American continent with a central artery. These workers, in no short order, helped solidify the westward future of the United States.

As a reflection of this herculean feat, the engravings on the legendary and ceremonial Golden Spike that symbolically united the rails of the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads hailed the Transcontinental for bridging the Atlantic and Pacific oceansreducing to one week what had been a perilous three-to-six-month journeyand healing the wounded nation. The Civil War had ended four years earlier, practically to the day, leaving a trail of destruction and a fractured Union in its wake. May God continue the unity of our Country, read the engraving on one side of the Golden Spike, as this Railroad unites the two great Oceans of the world. The Chinese had played a heroic and indispensable role in this achievementand Strobridge, who had played a leading role of his own in the project, now honored them for their enormous contribution.

Strobridge had come farnot just in distance from Sacramento, where the CPRRs work began, but in his attitudes as well. Five years earlier he had strenuously opposed the proposal to hire Chinese workers. He argued with his boss, Charles Crocker, one of the so-called Big Four, along with Leland Stanford, Collis Huntington, and Mark Hopkins, who served as directors of the CPRR, that the Chinese were not fit physically or temperamentally for the demanding work. Strobridge eventually relented, and Chinese, a few at first and then by the thousands, joined the construction effort. Proving themselves not just entirely capable but vital, in time they caused Strobridge to correct his error and drop his prejudice.

Hung Wah, for his part, had begun working for the CPRR in January 1864 after traveling to America from thousands of miles away in southern China. At Promontory he was in his mid-thirties, slightly older than most of the other Chinese, who were in their teens and twenties during construction, prime working ages for physical labor. He had received some education before coming to the United States and had a head for business, not to mention ambition: before Chinese were hired on to the CPRR, he was a prominent figure in Auburn, a town in the heart of the California gold country in the Sierra Nevada foothills. Agents of the CPRR turned to him to recruit workers, and he eventually became the leading Chinese headman over hundreds, and possibly thousands, of his compatriots working for the railroad. He handled their pay, living arrangements, and relations with the company. He had also survived years of personal difficulty and dangerous work, all the way through to the end.