A railroad worker perches atop the 1000 Mile Tree in Andrew Russells 1869 photo. The Weber Canyon, Utah, tree has since died, but was replaced by a new pine tree.

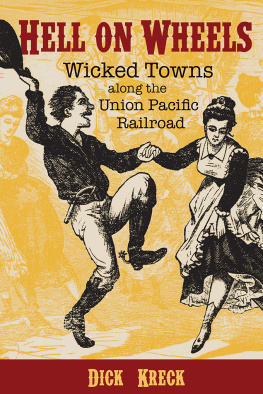

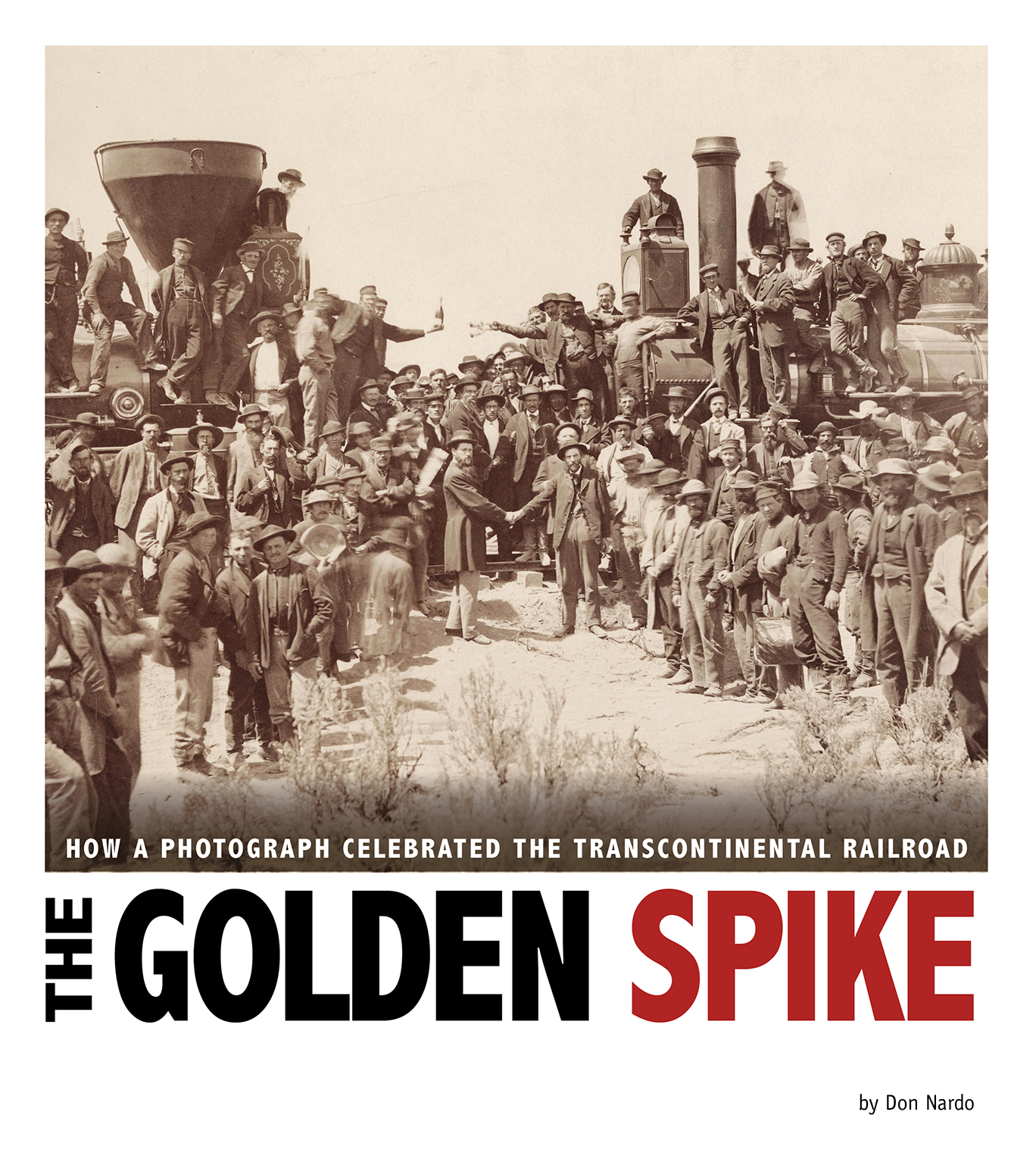

But the naysayers began to fall silent as the gigantic project slowly but steadily moved forward. In the mid-1860s, as the Union Pacific headed westward from Omaha, another companythe Central Pacific Railroad Companypushed eastward from California. Their goal was to meet somewhere in between, forming a single railway line that would bridge much of the continent. Early in 1869 it became clear that the historic meeting place would be in northern Utah.

Railroad workers in 1868 remove rock and soil, called digging out a cut, in Echo Canyon, Utah.

After getting his shot of the workers and the ancient tree in early January, Russell moved on. He and his three assistants, including Stephen Sedgwick, a young man with a keen interest in history, did their best to keep up with the railroad crews. The Union Pacifics foremen and their many workers moved along at a furious pace, often laying down 4 miles (6.4 km) or more of track in a day.

Russell and his aides had to take photos of more than the work itself. They were also expected to photograph the towns and scenic wonders through which the railway line passed. That required them to travel back, forth, and sideways along the route, looking for and documenting whatever Russell thought was most significant.

In the 1860s taking photos, especially outdoors, was a slow, painstaking procedure. Including the processing phase, taking a single shot could consume two hours or more. So it was not unusual for Russell to fall behind the work crews, forcing him to catch up on his way to another camera setup. Usually he had no idea what his next subject would be, so he rarely could plan ahead very far.

One major exception loomed on the horizon, however. Now that the Union Pacific tracks were nearing the spot where they would connect with those of the Central Pacific, he needed to plan. The ceremony marking the event was expected to engage a worldwide audience, and he would be one of only a handful of photographers present. To maintain his reputation, he needed to be as organized and otherwise prepared as possible.

It would have been far easier for Russell to do his job if he could have traveled light. But that was impossible for him, as it had been for Mathew Brady and the other well-known Civil War photographers. The typical equipment they carried included a box camera weighing up to 30 pounds (14 kilograms), a second device called a stereo camera because it captured two images at the same time, a collection of delicate glass plates and lenses, many bottles of chemicals for sensitizing the glass plates and developing the photos, and a tent that could be a mobile darkroom. All of this equipment, some of it fragile, had to be carried by wagon. And that slowed Russell and his assistants considerably, particularly in the rugged terrain through which the railway passed.

Russell and other photographers of the times employed a complex and very time-consuming method of creating pictures. Wet-plate process was only one of its many names. The photographer first cut a glass plate into the desired size. Often it was 10 by 13 inches (25 by 33 centimeters), but there were several other sizes. He or she then mixed chemicals and carefully poured a sticky mixture of collodion onto one side of the plate. The photographer then went into what was called a darkroom, even though for field photographers the room was often a black tent or a wagon.

Railroad foreman Jack Casement walks by Russells field darkroom wagon near the tracks in Utah.

In the darkroom the photographer sensitized the plate in a bath of silver nitrate for several minutes before placing it in a lightproof wooden plate holder. The next steps were to insert the plate holder into a slot in the camera box and, while the plate was still wet, to aim the camera at the scene to be photographed. Then the photographer removed a dark slide from the plate holder to expose the plate to the still-covered camera lens. There was no shutter, so the photographer took off the lens cap to expose the plate to the light for several seconds. The photographer then replaced the lens cap, reinserted the dark slide, removed the plate holder, and took it inside the dark tent or wagon. He or she then took the plate out of the holder and developed it in the dim orange light coming through the small safe light window in the tent.

Despite the difficulties and awkwardness of photography at the time, everyone involved agreed that it had to be used to document the historic venture. And in addition to the historical significance of the railroad photos, there was money to be made when photographers sold their images. It was becoming obvious that simple words and drawings were no longer enough to portray major news events. The photographic medium, which had been invented earlier in the century, also had to play its part. In 1867, two years before the completion of the first transcontinental railroad, a Philadelphia magazine declared, Nothing seems beyond the reach of photography. It is the railway and the telegraph of art. The telegraph detects and catches the thief, and so does photography. The railways carry us to points afar, and so does photography[in fact] it does more.