By the same author

GRANITE LAUGHTER & MARBLE TEARS

CONTES INTIMES

FIGHTING YANKEES

SPIKED BOOTS

THE STRANGEST BOOK IN THE WORLD

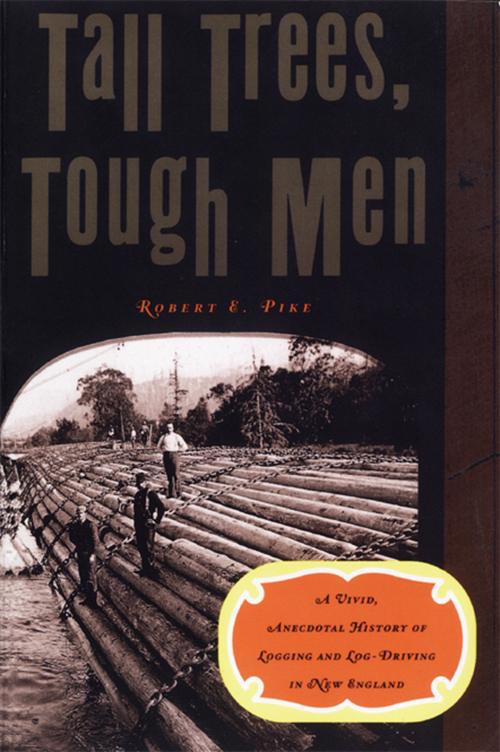

TALL TREES,

TOUGH MEN

By Robert E. Pike

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

New York London

First published as a Norton paperback 1984; reissued 1999

Copyright 1967 W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

The Rivermen appeared in American Heritage, February, 1967.

All rights reserved.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Pike, Robert Everding.

Tall trees, tough men, by Robert E. Pike. New York, W. W. Norton [1967]

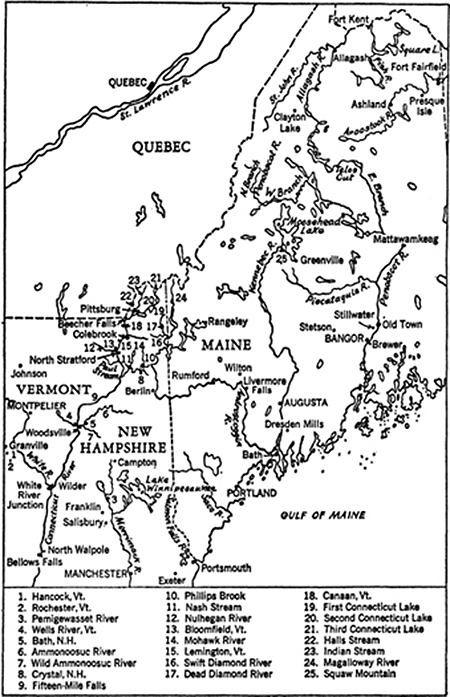

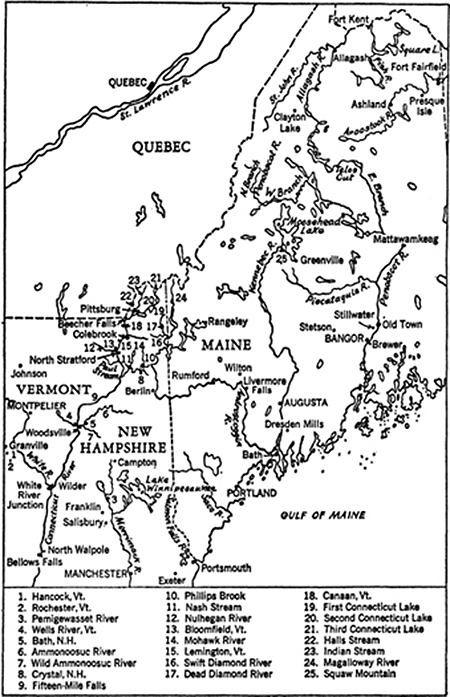

288 p. map, plates (incl. ports.) 24 cm.

Bibliographical refernces included in Foreword ()

1. LumbermenNew England. I. Title.

HD8039.L92U57 331.7'63'49820974 -11092

MARC

ISBN 978-0-393-31917-0

ISBN 978-0-393-24860-9 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N. Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London WIT 3QT

To Frederick A. Noad, Esq.

In Memory of the Afternoon We Were Sluiced on Hurricane Ridge

THIS BOOK has been a labor of love. To write it I have drawn freely from printed sources, oral reminiscences, and my own experience in the woods and on the river. I hope that the general reader will find the book interesting and that the expert will not find it inexact. Anyway, if it affords pleasure I shall have been amply rewarded.

It would be tedious to list all the printed sources I have utilized, though I cite most of them in the text, and all the people who have helped me in one way or another, but here are the principal ones:

Chief among the printed works are E. Francis Belcher, Logging Railroads in the White Mountains (a series in the magazine Appalachia); W. R. Brown, Our Forest Heritage; Perley W. Churchill, Making and Driving Long Logs; Philip T. Coolidge, History of the Maine Woods; Harold A. Davis, An International Community on the St. Croix; Fannie H. Eckstorm, The Penobscot Man; Alfred G. Hempstead, The penobscot Boom; Richard G. Wood, A History of Lumbering in Maine 18201861; Austin H. Wilkins, The Forests of Maine, and two periodicals, The Northern, formerly published by the Great Northern Paper Company, and Felix Fernalds Pittston Farm Weekly.

Photographs, many of them extremely rare, and from many scattered sources, I give credit for as they appear in the book.

Among librarians I owe a great deal to Marjorie L. Marengo, Barbara L. Miller, Jean Stephenson, Robert Van Benthuysen, Margaret A. Whalen, Effie S. Willey, and Janet Bagonzi.

For oral reminiscences I am especially indebted to Will Andrews, Tom Cozzie, Herbert L. Cummings, Bill James, Dan Murray, Ludwig K. Moorehead, Frederick A. Noad, Harl Pike, Frank Porter, Omar Sawyer, and Ralph Sawyer, eleven men who are still very much alive on this tenth of May, 1966, although their combined ages total over a thousand years; and to dozens of good men now dead and gone whom I knew and worked with years ago: George Anderson, Will Bacon, Dan Bosse, Vern Davison, Jack Haley, Ed Hilliard, Bert Ingersoll, John Locke, Orton Newhall, Phonse Roby, Win Schoppe, et al.

And a special word for Katherine Henry Benedict.

TALL TREES, TOUGH MEN

A man was famous according as he had lifted up axes upon the thick trees.

PSALMS LXXIV.5

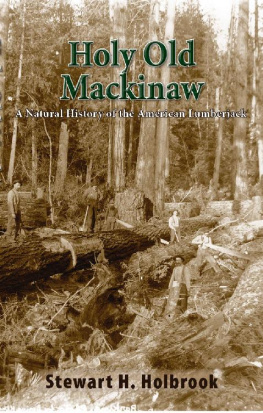

ONE OF the great dramas in the development of the United States is the history of lumbering. It is an epic story of courage, of great hazards and difficulties overcome, of success and failure in a struggle to provide some of the necessities of mankind. And the key to that history, to that drama, is the Axe.

Hand-hewn white pine built the houses for humans and the barns for their domestic animals, and a million hulks rotting in every port and on every sea-coast in the world today once took lumber and sea-power around the globe. It was the axe, even more than the rifle, that conquered the North American continent.

The axe is doubtless one of the oldest inventions of man. We have stone axes from the Stone Age, and bronze axes produced after metal was discovered. And axes have always been a symbol of power: in Crete, axes were worshiped; medieval knights used them as weapons; they figure on noble coats-of-arms; they beheaded kings and princes; they scalped American pioneers; and they denuded vast parts of Asia and other continents.

But is was in America that the axe reached its highest development. Nowhere else in the world was it used so much, did it undergo such change, was it adapted to so many uses. The first pioneers from England found the whole eastern seaboard covered with dark and hideous forests. The rocking pines of the forest roared to welcome the Pilgrims, and fearsome animals and fearful red men lived among those roaring pines. Untouched by an axe, those forests, especially in the Northeast, spread out for hundreds of miles, solid masses of giant trees that barely let through the sunlight. The old coureurs-de-bois grew sallow from lack of light.

To the early settlers, trees were a nuisance except when used for lumber. They had to cut them down in order to make farms. Indian-fashion, the white men girdled the trees in order to kill them and let in the sun. The deep mold, formed of aeons of fallen leaves and rotten tree-trunks, could be scratched with a wooden stick and produce more wheat to the acre than men in Europe had ever dreamed possible. Grass for the animals grew shoulder-high as the hardy settlers pushed ever back along the river intervals onto the hardwood ridges.

It was the axe that permitted them to do so. Every man and boy could handle one, just as today every man and boy handles the steering wheel of an automobile. And almost immediately there sprang up a special breed of man, the logger, or woodsman, or, as he was later called, the lumberjack. He reached his apogee in the late nineteenth century, and now he has almost disappeared.

Most farmers had little to do in the winter, and most of them went to work in the woods, as teamsters, axemen, log-drivers, in order to earn a little extra money. But they were primarily farmers. They handled an axe competently, but they were not experts.

The experts were men who worked in the woods all the time. The difference in their performance was as conspicuous as that of an expert in any linethey demonstrated ease and perfection and skill brought about by long, hard hours of trying to become perfect. They were Axemen, men who cherished their axe, who shaved down the handle until it sprang like whalebone, who carried an oilstone to keep the edge of their weapon always keen enough to shave withthough very few of them ever used it for that purpose. They knew exactly how to hang an axethat is, to insert the handle, or helve, into the axe-head at the proper angle so it fitted the owner, and no other man. The importance of this primary mark of an axeman was magnificently demonstrated by Big Dan Murray (in 1966, ninety-five years old) of the Androscoggin, who was once accused of stealing an axe. He showed his complete disgust with the charge when he said, Why in hell should I steal his axe? It wouldnt be hung right for me!

The skill of these men was phenomenal, whether in cutting down trees or in making small, decorative furniture. Saws are a comparatively recent invention. Eighty years ago woodsmen went into the woods armed only with axes and built their camps and horse-hovels, their sinks and chairs, their doors and bunks, all with an axe. Such men would have been ashamed not to leave a smooth scarf on a tree, and in their hands the broad-axe squared both hardwood and softwood timbers as evenly as would a saw.

Next page