THOSE LAKE PEOPLE

THOSE LAKE PEOPLE

STORIES OF COWICHAN LAKE

LYNNE BOWEN

Copyright 1995 by Lynn Bowen

95 96 97 98 99 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from CANCOPY (Canadian Reprography Collective), Toronto, Ontario.

Douglas &. Mclntyre

1615 Venables Street

Vancouver, British Columbia

V5L 2H1

Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data

Bowen, Lynne, 1940

Those lake people

ISBN 1-55054-464-0

1. Cowichan Lake Region (B.C.)History I. Title.

FC3485.C684B69 1995 971.17 C95-910573-5

F1089.C73B69 1995

Editing by Barbara Pulling

Jacket design by Peter Cocking

Text design by Peter Cocking and DesignGeist

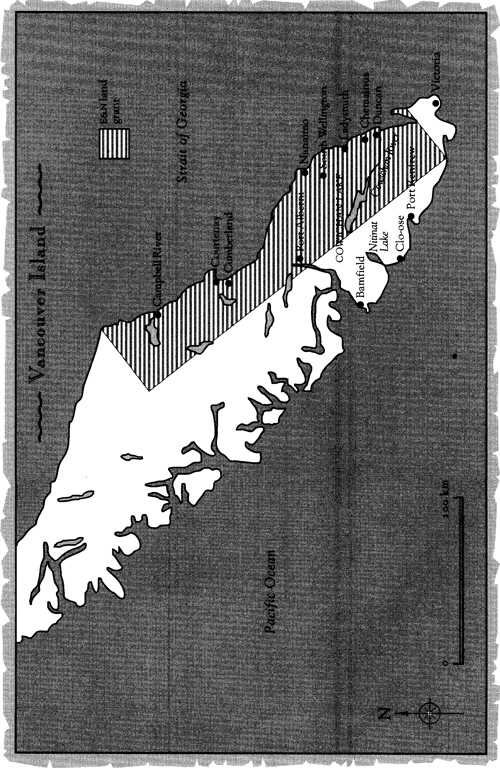

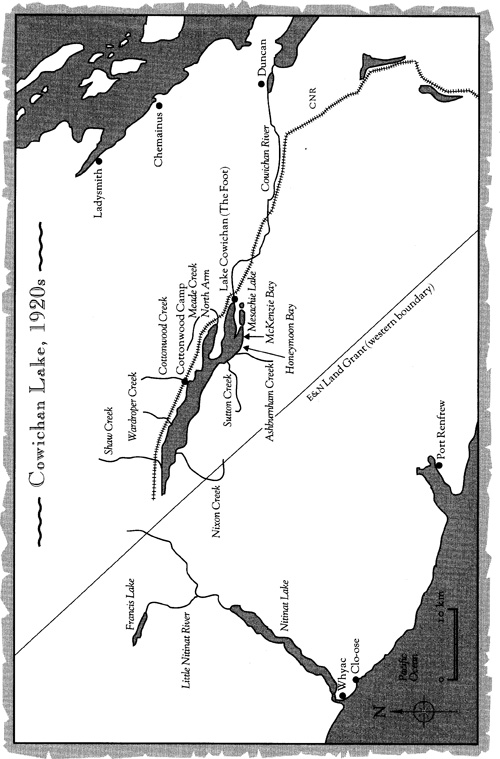

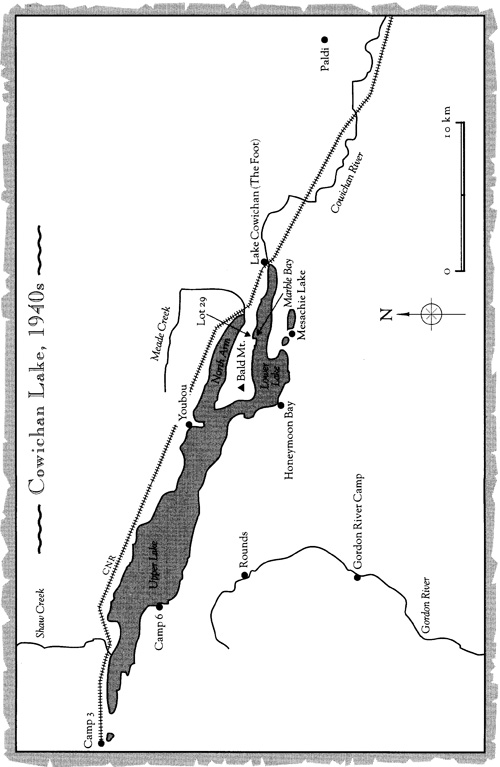

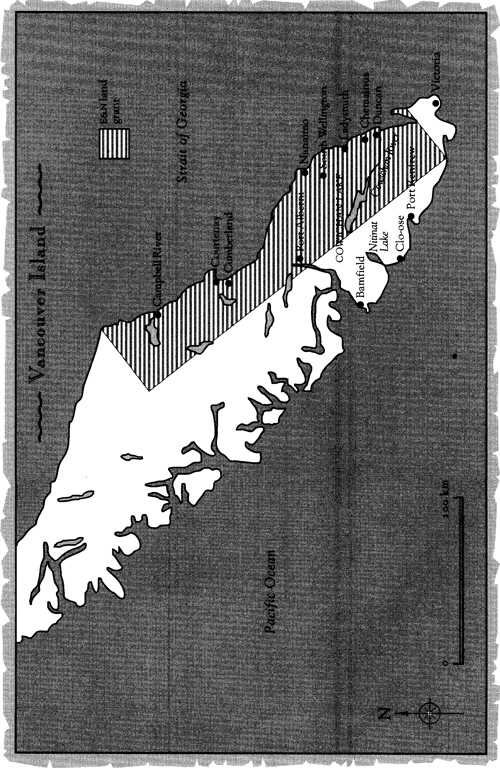

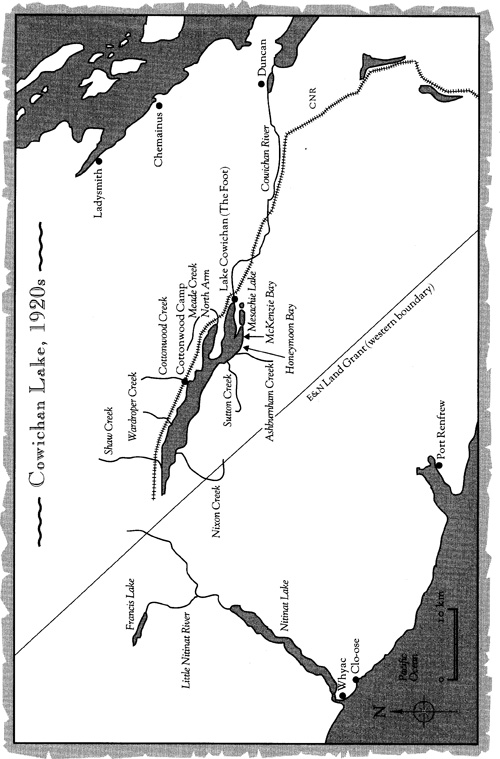

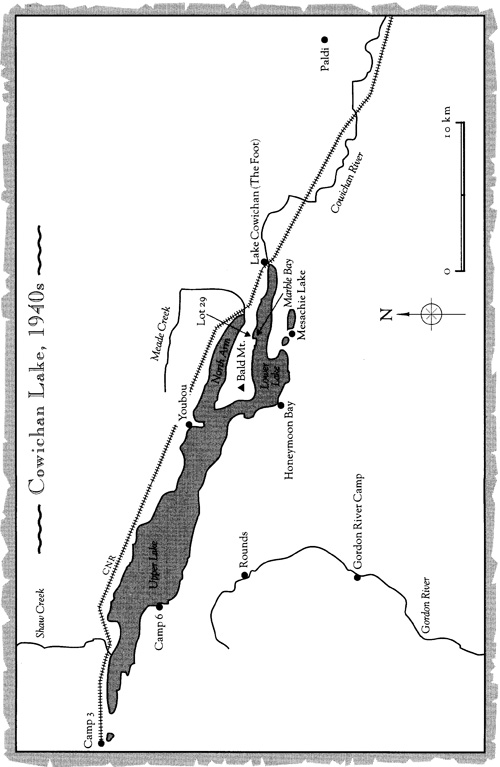

Maps by Andrew Bowen and DesignGeist

Front cover photograph: A group returns from a picnic at Marble Bay, c. 1916

Eva Beech Collection, Kaatza Station Museum P984.2.12

Typeset by Brenda and Neil West, BN Typographies West

Printed and bound in Canada by Friesens

Printed on acid-free paper

The publisher gratefully acknowledges the assistance of the Canada Council and of the British Columbia Ministry of Tourism, Small Business and Culture.

Financially assisted by the Province of British Columbia through the British Columbia Heritage Trust.

To H.P. with love

Table of Contents

Preface

FOR THE PURPOSES OF THIS BOOK, Cowichan Lake includes the region from Paldi to the lake and beyond to Port Renfrew and the Nitinat Bar. I have chosen to tell the story of this area through the lives of some of its people.

Outsiders have tended to view the people at the lake uncharitably at times. Those lake people were thought to be too uncivilized, too poor, too rich, too eccentric or too foreign. The lake itself was too hard to get to, too rough in a storm and its shores were too heavily treed. All in all, fertile ground for a writer.

Those Lake People had its genesis in a request by Wilma Wood, then project manager of the Cowichan Chemainus Valley Ecomuseum Society, who asked me to write a social history of the area. Although it soon evolved that I would write the book independently, I did so with the help and encouragement of Barry Volkers, Pat Foster and Jean Brown of the Lake Cowichan Heritage Advisory Committee.

Some groups of people were more accessible to me than others. I hope that researchers in the future will be able to track down descendents of the Chinese and Japanese people who lived at the lake, and present a more personal picture of their involvement.

The First Nations story presented me with a dilemma. Accepted wisdom has been that no particular aboriginal group lived permanently at the lake, although several tribes hunted, fished and built cedar canoes there. This interpretation seems at odds with the current debate about land claims, a debate, I fear, that will not soon be resolved. In the spelling of various names and the identity of various tribes and bands, I tried to seek a balance between mid-nineteenth-century misinterpretation and late-twentieth-century preferences. I apologize for any mistakes that may have resulted.

On a less sensitive issue, I have chosen to use imperial instead of metric measurements because the former were used when most of the events took place.

There have been other books written about the lake, but the one I particularly recommend to anyone interested in a detailed and highly competent account of the forest industry is Richard Rajalas The Legacy and the Challenge (Lake Cowichan Heritage Advisory Committee, 1993).

There are several people in this book whose families I met while researching my two books on coal miners. When the Vancouver Island mines closed, these people moved to the lake and became leaders in the union movement. Our politics are miles apart, but they feel like old friends.

Colleagues who share their contacts and research are the most selfless of individuals. The leader in this regard is Professor Jean Barman, who came up with experts, such as Ruth Sandwell and Sarjeet Singh, whenever I needed one. Dr. Patrick Dunae led me to Negley Farson and the raw data from the 1891 census, which Dr. Dunae and his students have analysed and made available to researchers. Robert Griffen of the Royal British Columbia Museum shared his expertise on sawmills. Professor Allen Seager came through, as he always does, with explanations to make cloudy issues clearer. Dr. John Whitelaw, in his lucid fashion, explained the gruesome facts surrounding the sinking and subsequent resurfacing of dead bodies. Dr. Richard Rajala read the manuscript for errors in logging and union history, and Trevor and Yvonne Green for mistakes in peoples names and circumstances. Any errors still remaining are my own.

My thanks too to Gordon Miller, librarian at the Pacific Biological Station; Al Lundgren, photographic archivist of Local 1-80, IWA Canada; the staffs at the British Columbia Archives and Record Service in Victoria and the Cowichan Valley Museum in Duncan; to Barbara Lyall, Judy Fraser, Ken Lyall and Dick Bowen, my proofreading team; and to Bruce Atkinson, D. Lukin Johnston and Lois Macmillan. Most of all, I would like to thank Barbara Simkins, curator of the Kaatza Station Museum, for service of the most professional kind and good conversation over many brown bag lunches.

And speaking of food, it isnt only armies that travel on their stomachs. Dawne and D. J. Grant gave me dinner and a bed many times during the research phase. And three couples offered both valuable information and gracious hospitality: Roger Wiles and Susan Bannerman; Barry and Lou Volkers; and Trevor and Yvonne Green.

Thank-you to Rob Sanders for allowing himself to be convinced, Barbara Pulling for insisting on excellence, and the rest of the staff at Douglas & Mclntyre. And thanks to Wilma Wood for what she started.

CHAPTER ONE

An Easy Fortune

The timber was however of the most magnificent description. Within an area comprehended by our eye was an easy fortune for any man of the most moderate means.

ROBERT BROWN

WHEN FRANCIS JACOB GREEN FIRST saw Cowichan Lake, he was twenty-six years old and a world traveller. In the four years since he had left County Antrim in Ireland in 1883 because he didnt get along with his father, Frank Green had sailed across the Atlantic Ocean, ridden a train across the continent to San Francisco, worked his way up the West Coast selling odds and ends from a two-wheeled donkey-pulled cart, graded streets in Seattle, worked on a railroad survey party on Vancouver Island, and sailed to Australia and back to Victoria. During that time, having apparently forgotten why he left home in the first place, he had advised his parents and siblings to come to the island. Which is why, when he returned from Australia, he had a reason to come to Cowichan Laketo see what two of his brothers and his sister were doing.

Annie Green was at the lake that summer to cook and act as hostess for her brothers Charles and Alfred, who had built a log hotel in the middle of a dark forest at the end of a rough trail. The trail, barely wide enough for a wagon and team, meandered for twenty miles from Duncan, the nearest outpost of civilization. The hotel sat on the bank of the Cowichan River less than a mile below where it left Cowichan Lake.

Next page