ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Had Amelia Boesch not married William Ahten in 1903, this book might not have been written. Millie and Willys camp, the Amelia A along Hayne Boulevard, was the first to be owned in five generations of my family. Although I have no recollection of Aunt Millie, some of my fondest memories are of times spent at camps and of the stories about the lake told by her sister, my great-grandmother Augusta Gussie Boesch, and my great-grandfather Edward Knowera storyteller of major proportions. Through them and offshoots of family branches including members of the Maylie, Mondello, and Pohlmann families, I learned to love and respect Lake Pontchartrainhow could one not do that when embraced by family and the lake in a camp built just above its waters?

My lifelong friends Eddie and Shirley Krass and their children, Blake, Julie, Amy, and Gail shared countless days, invaluable work, and their outrageous sense of fun with us at the camp. I thank them and all friends who helped and joined us in making glorious memories.

Dan Rein, former Mayor of Little Woods, and his wife, Annette, owners of the Hayne Boulevard camp Six Little Fishes, shared wonderful stories about life on the lake. I am indebted to them for that as well as for being good neighbors on the lake who never failed to come to our rescue.

Finally, and most importantly, I thank Meredith and Vincent Campanella, my parents, for giving my children, my husband, and me the opportunity to live on Lake Pontchartrain in a camp built in 1925. It was first named St. Johns Cottage, then Lakecrest Cottage, and finally renamed for my familyCamp-a-Nella. It was a treasure.

Information found here would not have been available without the work of writers, photographers, historians, archivists, and local nostalgia buffs who researched the history of Lake Pontchartrain long before I began this endeavor. Special thanks to Irene Wainwright, archivist of the New Orleans Public Library, for assistance in acquiring many of the photographs found here. Other photographic sources include the Library of Congress and the Louisiana Digital Collection, among others. Much information about jazz on the lake was gleaned from the Red Hot Jazz Archive. Family photographs and invaluable information were generously shared by Connie Adorno Barcza, Dawn Bowers Benfield, Beth Fury, Anne Harmison, Henry Harmison, Julie Krass Kroper, Jason Perlow, Amy Cyrex Sins, and Poppy Z. Brite. Uncredited photographs are in the authors collection.

Find more books like this at

www.imagesofamerica.com

Search for your hometown history, your old

stomping grounds, and even your favorite sports team.

One

THE BEGINNING

Historic markers near Lake Pontchartrain offer terse commentaries but pay homage to Native Americans who first inhabited the land surrounding the lake. They include: Lake Pontchartrain... Indians called it Okwa-ta, wide water, New OrleansFirst sited as Indian portage to Lake Pontchartrain and Gulf... , The Old PortageShort trail from Lake Pontchartrain to river shown by Indians to Iberville and Bienville, 1699, Mandeville... Near this site Bienville met, in 1699, Acolapissas who reported that, two days before, their village had been attacked by two Englishmen and 200 Chicasaws, and Tangipahoa... Town named for Indian tribe.

The Tangipahoa people are best remembered now for the parish as well as the river named for them. Tangipahoa comes from an Acolapissa word meaning those who gather corn. The Tchefuncte tribe was likewise recognized; the river that enters Lake Pontchartrain at Madisonville bears their name.

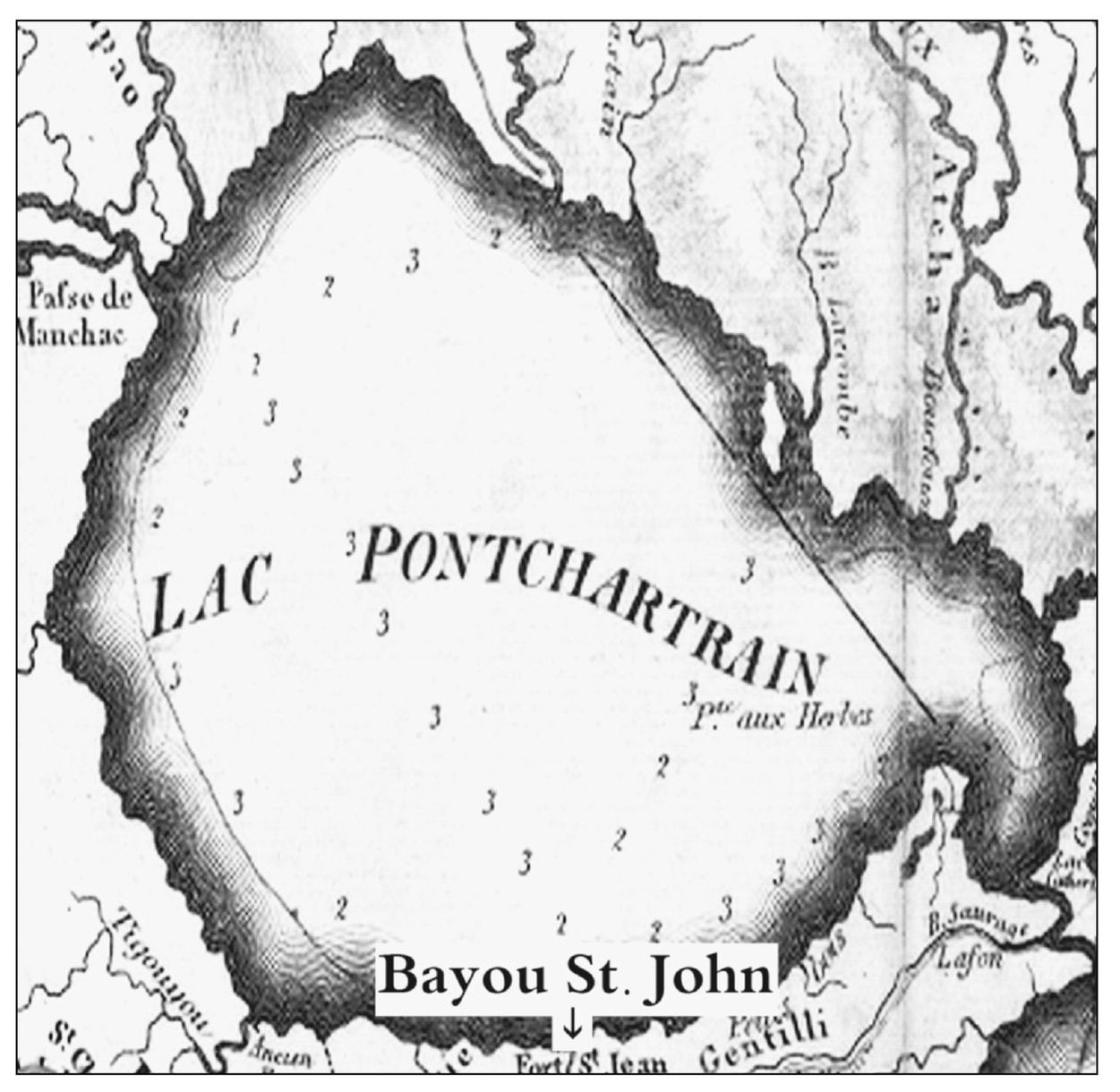

Prior to the arrival of Europeans, a Choctaw village of the Houmas tribe (who viewed the crawfish as a sign of bravery) settled along Bayou St. John where it met Lake Pontchartrain. They named the lake Okwa-ta . Bayou St. John was called Bayouk Choupic for the mud fish (also known as bowfin or cpyress trout) that lined its edges. The word bayou comes from the Choctaw word for minor streams.

The bayou was used for transportation and trade. Native Americans discovered that by using it and a natural, elevated ground path (now Bayou Road), they could travel from the Mississippi River at present-day New Orleans to the lake, through the Rigolets Pass, and into the Gulf of Mexico.

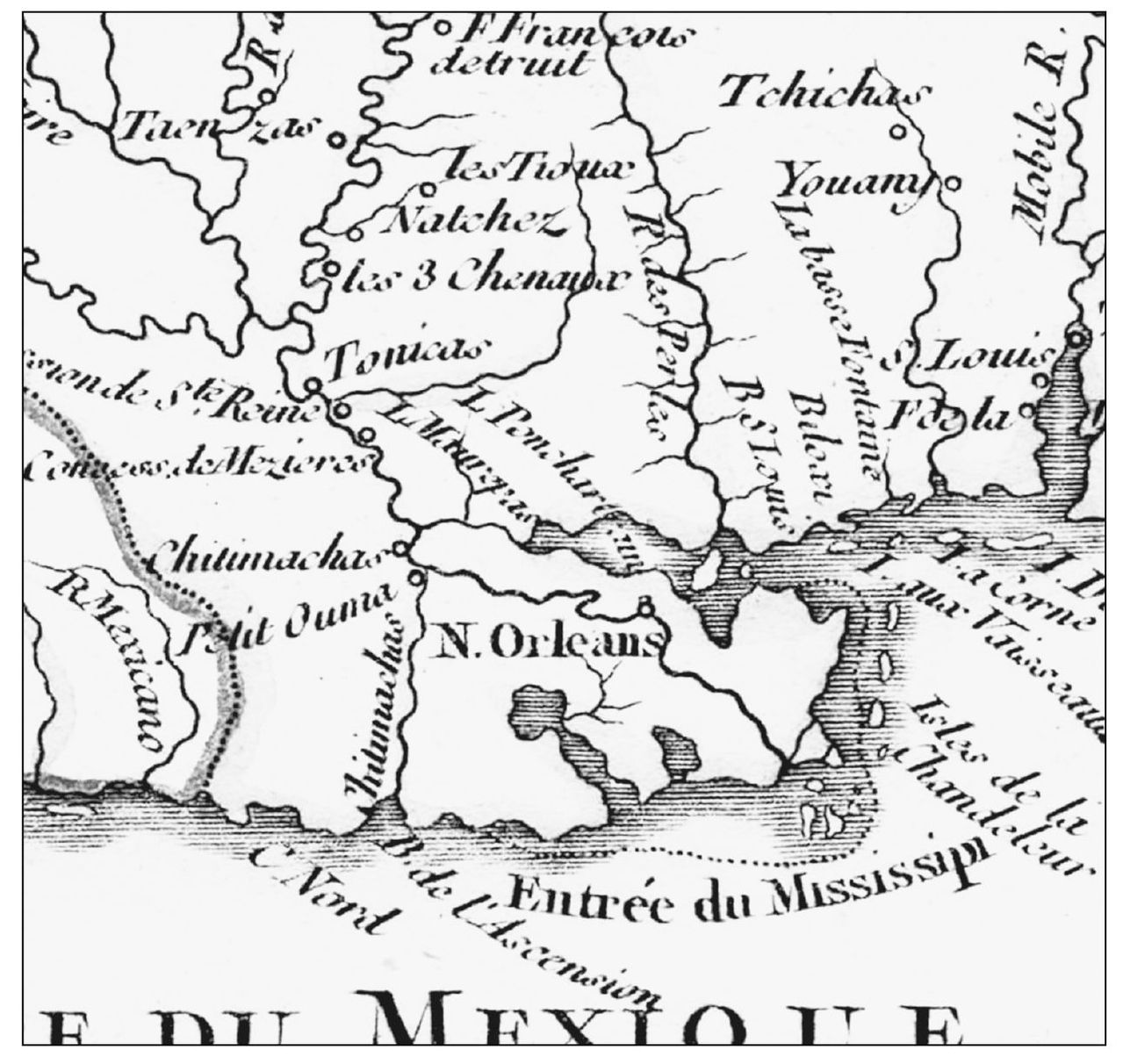

When the French arrived, they sought a shorter route from their small settlement to the gulfshorter than the plodding, meandering upriver passage from the river delta. It was the Biloxi tribe who showed them the way. One could say that had the native people not so generously shared their knowledge, the history of Lake Pontchartrain and the surrounding communities might be quite different.

The French built Fort St. Jean at the mouth of the bayou to protect their settlement from attack via the lake. Spanish governor Carondelet constructed a canal to connect the city to the bayou. It would be the fist of many plans to engineer a direct route to the lake. By 1818, a lighthouse guided sailors there, and two more forts, Pike and Macomb, were constructed on the eastern shore.

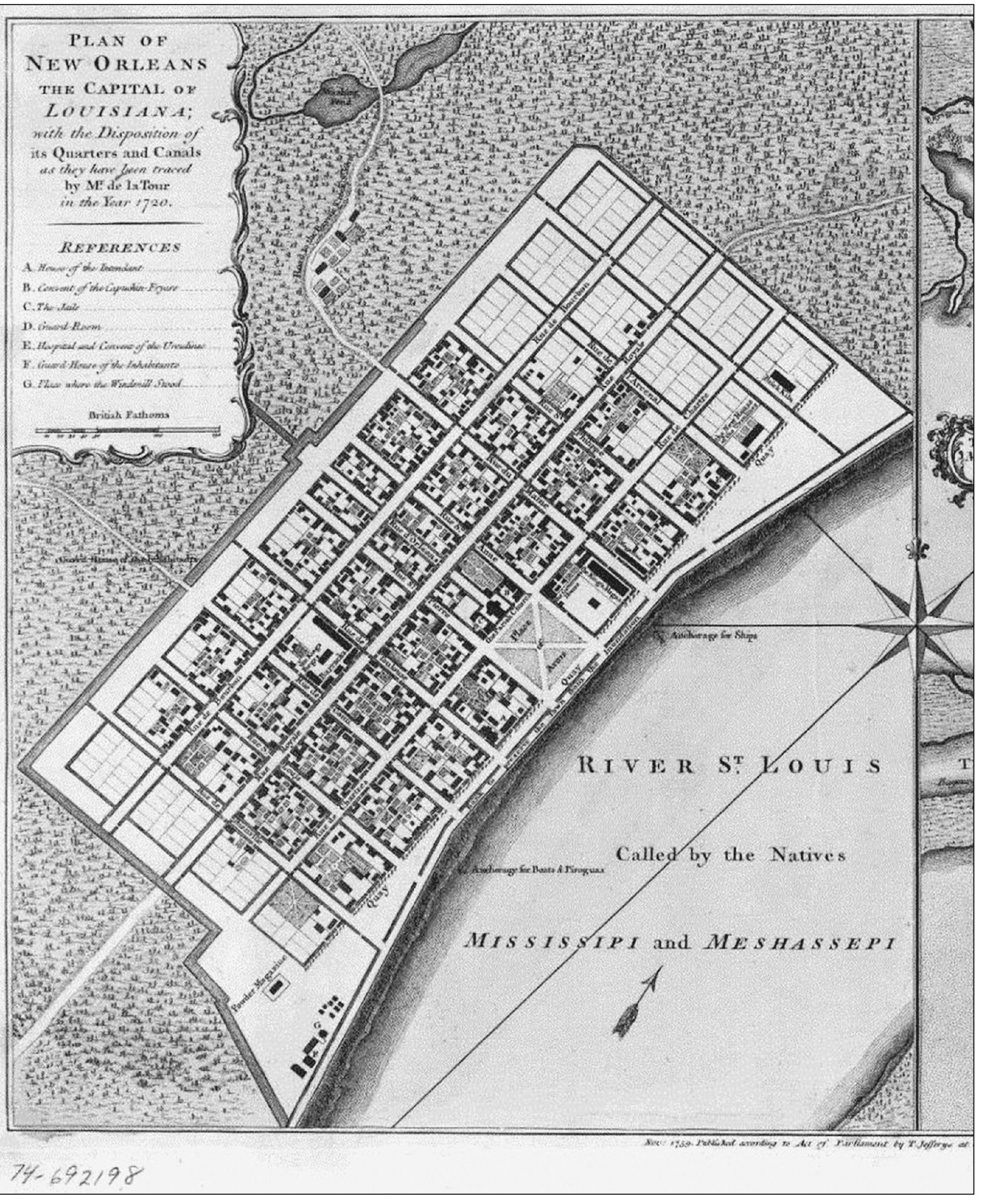

This map includes an overall view of Lake Pontchartrain and indicates the approximate location of Bayou St. John at Lake Pontchartrain.

This portion of a 1749 French colonial map entitled Cours du Mississipi et La Louisiane by Robert de Vaugondy shows Native American tribe locations as well as Lake Pontchartrain and a primitive view of the east/ west navigational shortcut between the Gulf of Mexico and the lake. (Courtesy Louisiana Digital Library.)

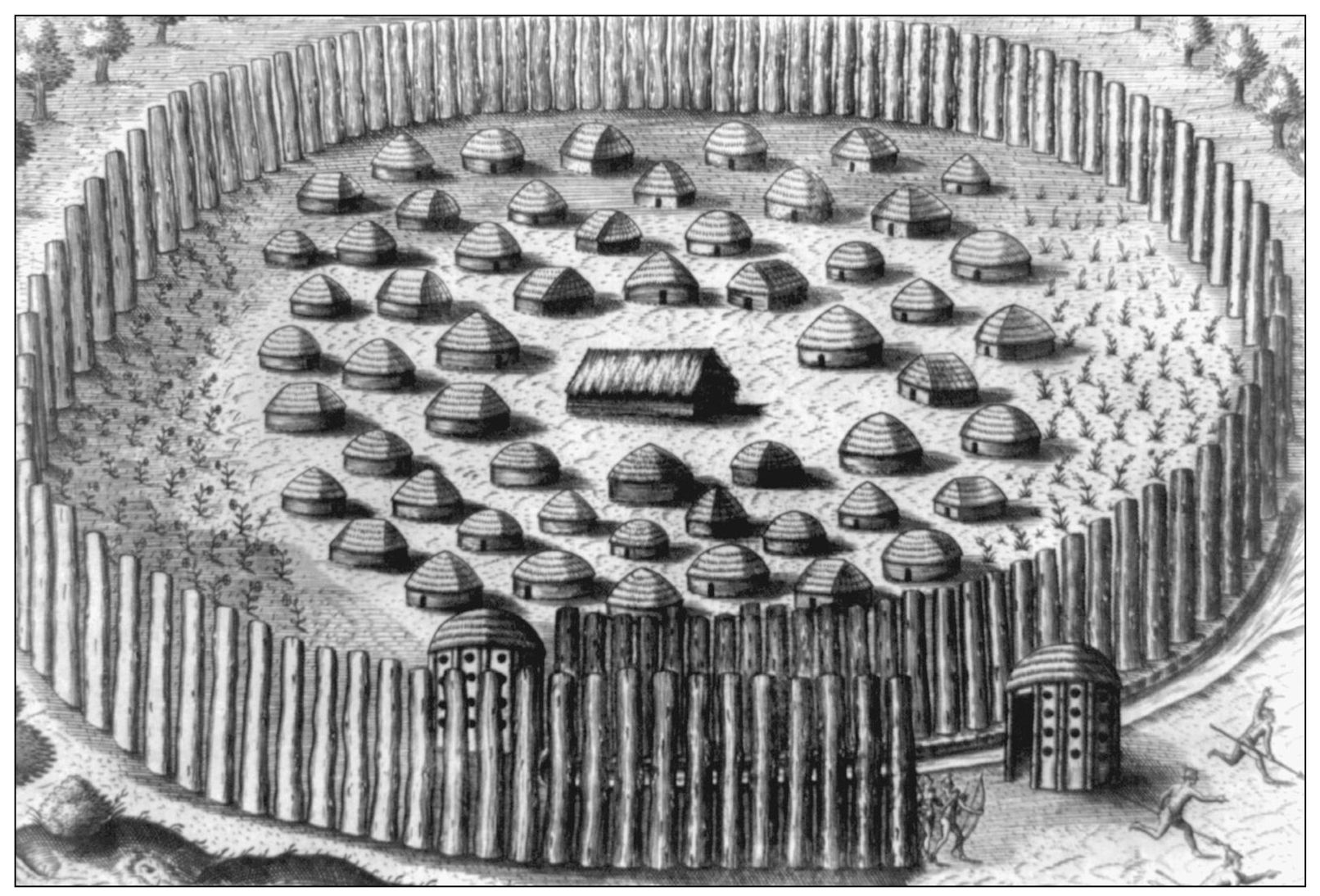

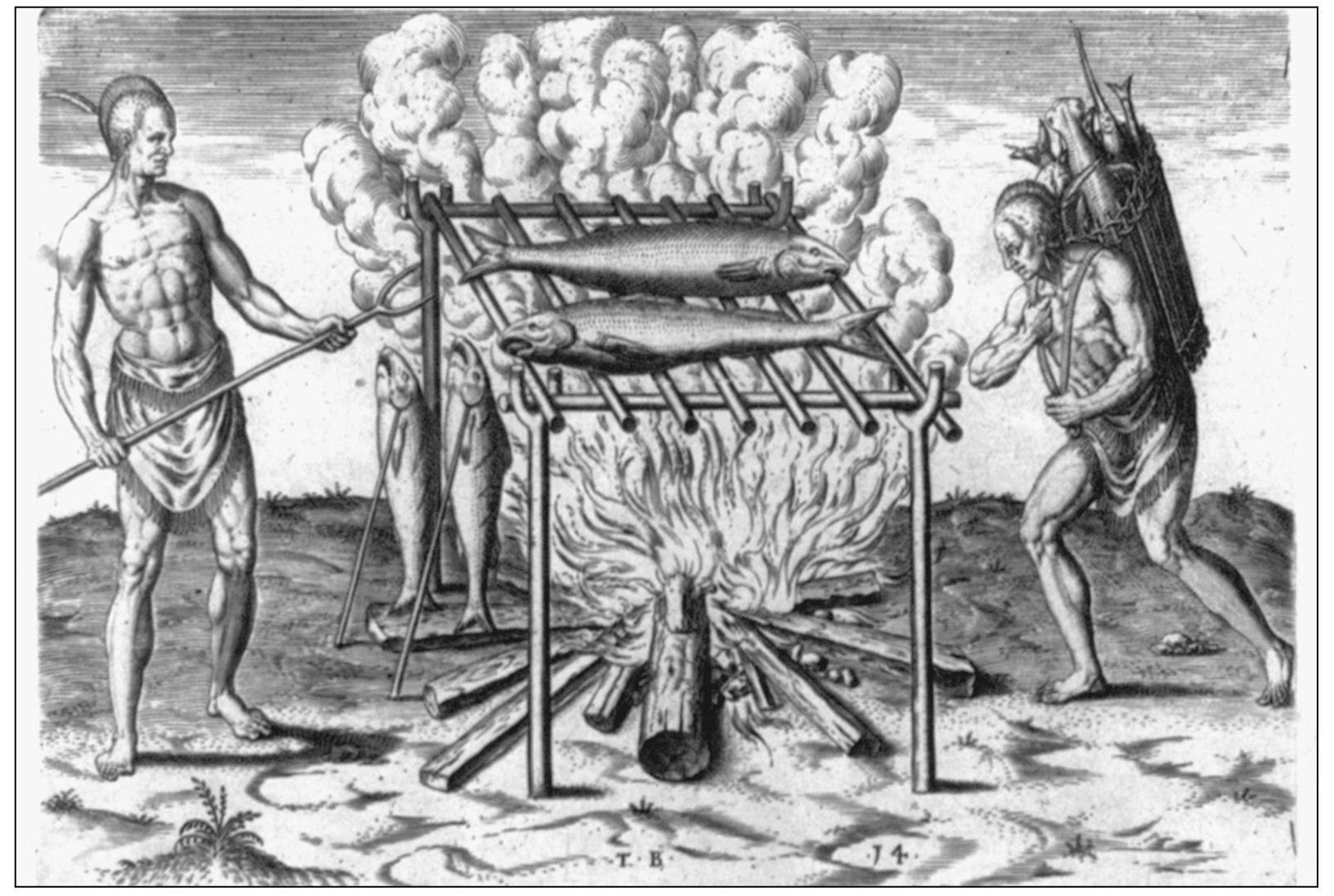

When Iberville came upon the spot he would later name New Orleans, he saw a Bayougoula village comprised of straw-roofed huts surrounded by a circular protective wall of cane and saplings. (Courtesy Library of Congress.)

The Houmas tribe called Bayou St. John Bayouk Choupic for the mud fish, which lined its edges. (Courtesy Library of Congress.)

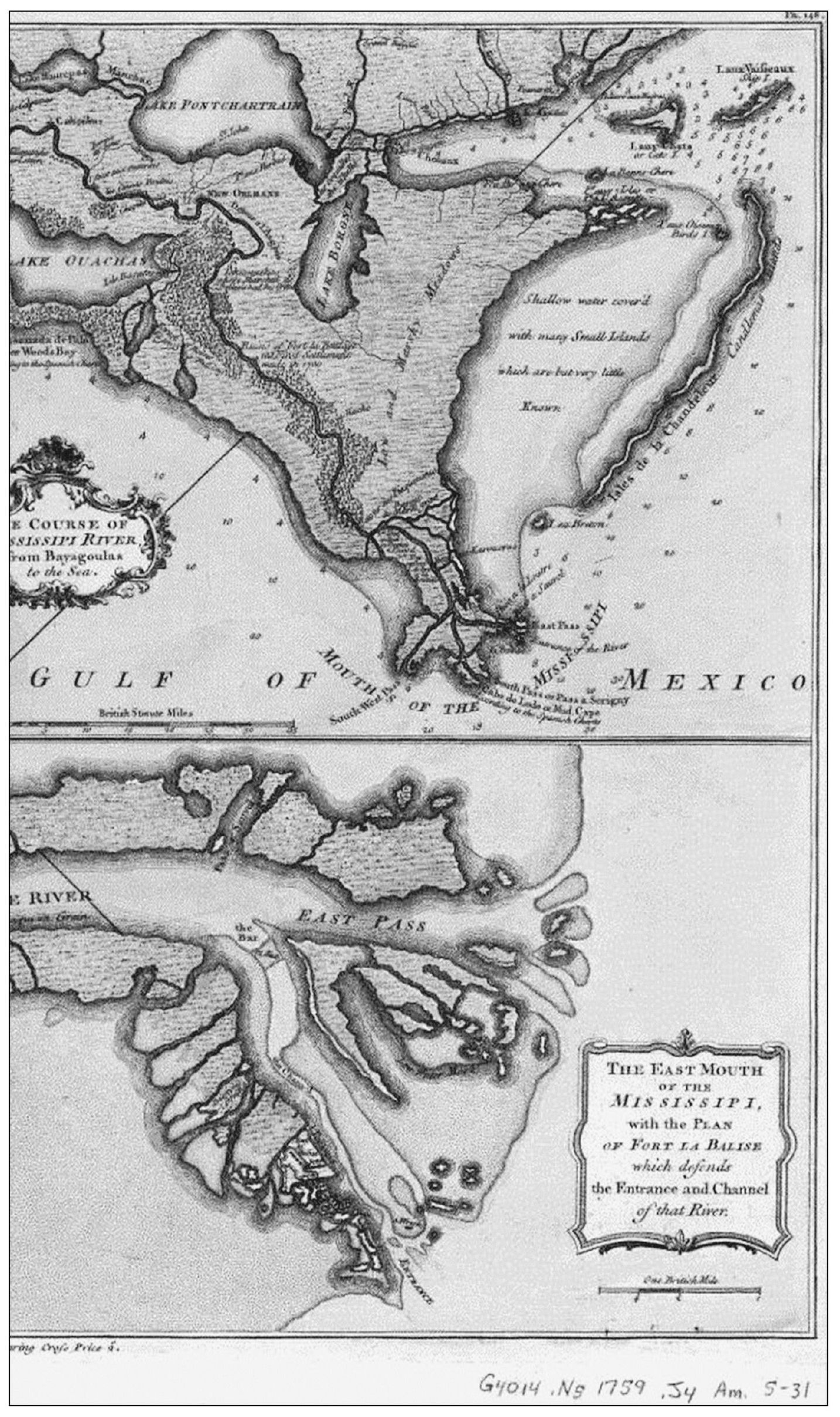

This 1759 map illustrates the short natural trail (left) through surrounding swamp that connects the Mississippi River (and New Orleans) to Bayou St. John and the connecting waterways (top right) leading to the Gulf of Mexico. (Courtesy Library of Congress.)