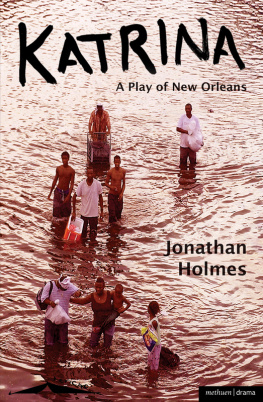

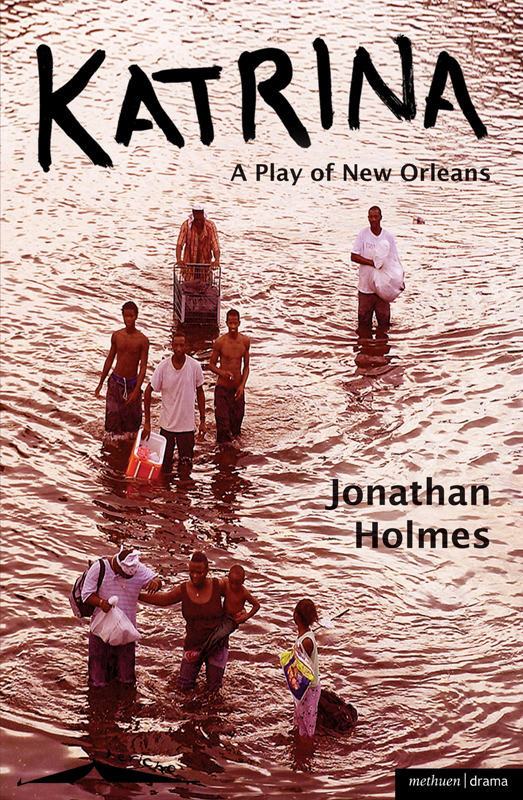

Jonathan Holmes

Katrina

A Play of New Orleans

Methuen Drama

Published by Methuen Drama 2009

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Methuen Drama

A & C Black Publishers Limited

36 Soho Square

London W1D 3QY

www.methuendrama.com

Copyright Jonathan Holmes 2009

Jonathan Holmes has asserted his rights under

the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

to be identified as the author of this work

eISBN: 978-1-40813-340-8

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from

the British Library

Typeset by Country Setting, Kingsdown, Kent CT14 8ES

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

Bookmarque Ltd, Croydon, Surrey

Caution

All rights whatsoever in this play are strictly reserved and application

for performance etc. should be made in the first instance to

Methuen Drama (Rights), A & C Black Publishers Limited,

36 Soho Square, London W1D 3QY. No performance

may be given unless a licence has been obtained.

No rights in incidental music or songs contained in the work are hereby

granted and performance rights for any performance/presentation

whatsoever must be obtained from the respective copyright owners.

No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by

any means graphic, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying,

recording, taping or information storage and retrieval systems without

the written permission of A & C Black Publishers Limited.

This book is produced using paper that is made from wood grown

in managed, sustainable forests. It is natural, renewable and recyclable.

The logging and manufacturing processes conform to the environmental

regulations of the country of origin.

Table of Contents

Theatre and Experience

by Jonathan Holmes

To try to understand the experience of another it is necessary to dismantle the world as seen from ones place within it, and to reassemble it as seen from his... To talk of entering the others subjectivity is misleading. The subjectivity of another does not simply constitute a different interior attitude to the same exterior facts. The constellation of facts, of which he is the centre, is different.

John Berger, A Seventh Man

In theatre, as in life, events are always observed from somewhere. There is always a point of view, changing constantly like life, theatre happens in more than two dimensions. It is the only medium with the capacity wholly to surround its audience with tangible reality, and it is the sole artform with the ability to create, as well as to represent, live experience.

To understand the world we need to comprehend the exterior as well as the interior structures of experience. Theatres great advantage over other media is that it has the potential to do this effortlessly. It can create exterior constellations of facts, in Bergers words, and it can depict the ways in which they transform or influence individual subjectivities. Other artforms cannot achieve this as readily, for the simple reason that they have not the capacity to sculpt four-dimensional space. The potency of theatre lies in this ability both to represent experience and to create it in the bodies and minds of all those present. It not only portrays change, it enacts it.

Theatre is able to dismantle one world and assemble another, both metaphorically and actually, all around us. The role of theatrical space is consequently not just scenic, but essentially political. In reality our experience of the world is primarily a sensory one; not only visual but also aural, tactile, olefactory. So it can be in theatre. In reality we react to space bodily we are moved in a physical as well as in an intellectual or an emotional sense. Why not too in the theatre? Crucially, such a conceptual and spatial reconfiguration in how theatre works is not in service of a new naturalism, where the focus is on representation, but rather attends to the actual experience of those present that of the storytellers, certainly, but most centrally that of the audience.

This kind of theatre does not supplant genuine experience, replacing it with the virtual; it is experience, of the same order and dimension as everyday life. We are all in the room together, manufacturing memories; why not be honest about it? The role of such theatre is not conspiratorially to pretend that an illusion is real (the job rather of politicians and priests), but to acknowledge that we are all sharing an actual, and possibly profound, experience together. There are no illusions, only experiences. This theatre is a kind of cubist artform, presenting simultaneously the many sides of experience, though it goes beyond anything painting can achieve by welcoming within itself the experiences of its audience, too. The audience is the subject of the performance as much as the narrative or the characters, and as central a participant as the actors or the crew. We do not need to be in a specially sanctified building for all this to obtain; it can happen more or less anywhere. After all, theatre is really a kind of refuge, not a market; it is naturally hospitable, not mercantile.

A consequence of all this is a re-imagining of the role of the audience. It ceases to be a band of consumers, paying for the familiar, and becomes instead a collective of witnesses, vital to the events integrity. Such a shift is partly ethical in nature, as auditors and spectators are free to choose how closely they engage with the material and how involved they become in the unfolding events. This is clearest when testimony is at the heart of the experience, as in Katrina, and the audience is witness to a form of public hearing of untold stories. The responses the stories engender are vital to their meaning, and the audience, by its presence, is a kind of collaborator in their authorship.

The function of any narrative is to make experience recognisable. Stories are the necessary means by which the oppressed articulate their oppression, and by which the abused seek to heal their wounds. They are the starting point for understanding, for awareness, and for empathy. They can be a vehicle for the transmission of joy. The shape that an individual storyteller gives to their experience can make us see the familiar afresh, make us see a situation as if for the first time. Stories, famously, make the stone stony the opposite of an anaesthetic is the aesthetic.

A theatrical emphasis on experience, then, points in two directions. As an act itself, attending a performance is experiential, we are a part of that event, part of the story, immersed in its sensual space and sharing responsibility for its occurrence. And as a representation, theatre serves to make the experience of others recognisable according to certain perceptual and cultural codes. The combination of the two means that as audience members our attention is directed many ways inward into ourselves, across to our fellow witnesses, outside the building and into the world, and often into the past, too. It follows that such a theatrical experience shatters boundaries between several parallel incarnations of us and them, of the powerful and the powerless. It is both empathetic and egalitarian, and so profoundly ethical.

It is in the counterpoint of these understandings, the sensory and the perceptual, that the potency of theatrical aesthetics resides. The more the body is engaged on its own terms with the work, the more those attending are involved, implicated and affected by the experience, and so the further any ethical potential is developed. In its emphasis on the sensory and the experiential, this kind of theatre prioritises the perception of individual bodies as ends in themselves and not as a means to some further representation. This is evident in the fact that, unlike much consumer-theatre, this kind of performance cannot exist without an audience present. Our theatre is an art of solidarity, not of division.