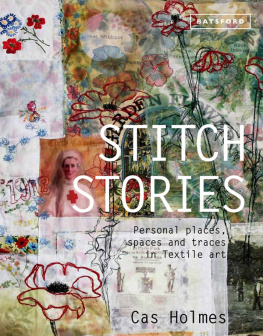

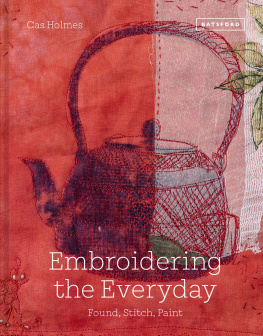

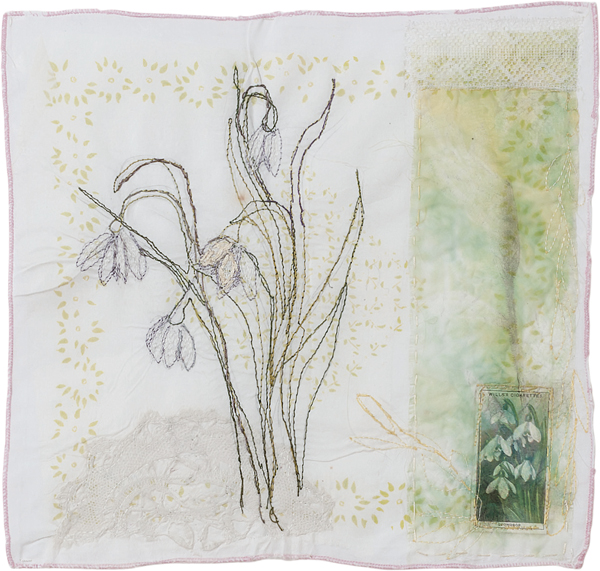

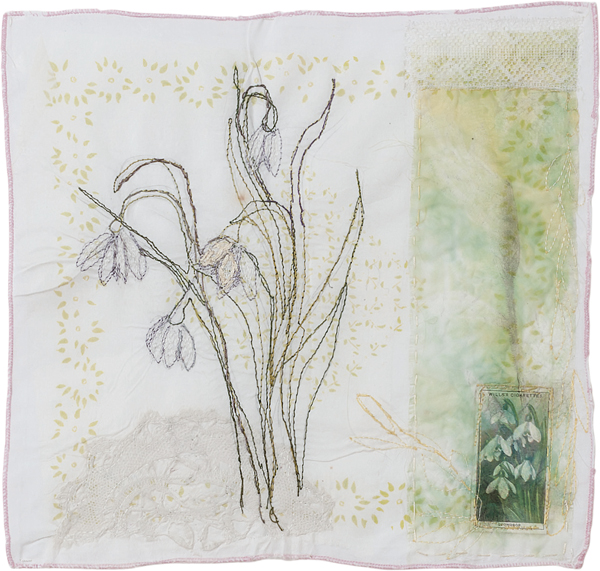

Cas Holmes, Snowdrop 2014, 27 x 27cm (10 x 10in). The image of the snowdrops on the vintage cigarette card is echoed in the free-machine stitch drawing.

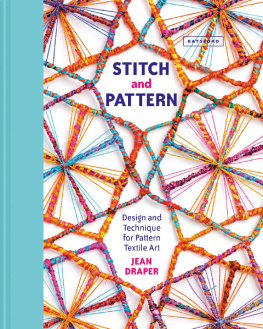

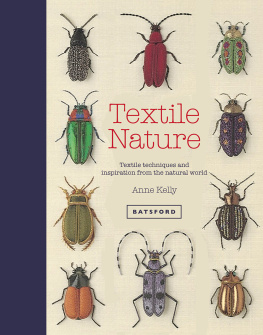

Contents

Introduction: finding inspiration for textile art

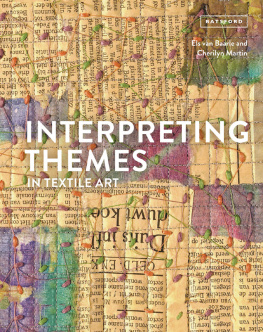

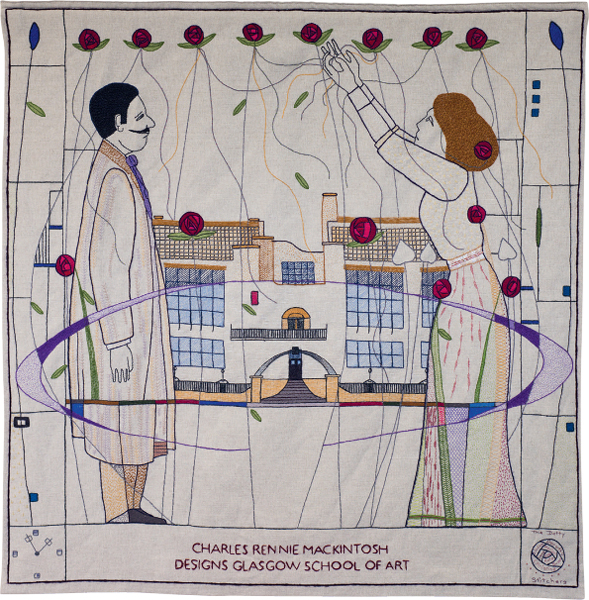

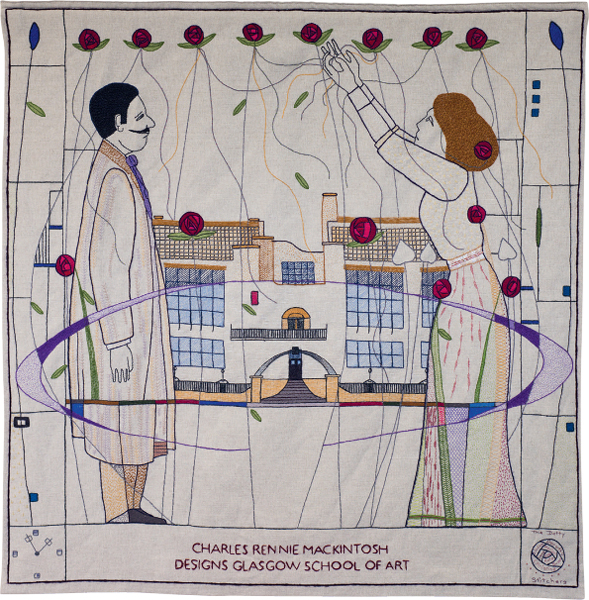

Great Tapestry of Scotland, Designed by Andrew Crummy. Stitch co-ordinator Dorie Wilkie. One of 164 panels totalling 1 x 124m (1 x 155yd). Image based on Charles Rennie Mackintoshs design for the Glasgow School of Art. Wool embroidered on to linen, 100 x 10cm (39 x 39in).

It is not often that you come across an artist that plays between the worlds of man and nature. Most find inspiration either in one or the other; we are all familiar with textile work that holds urbanity or nature as its core inspiration. However, Cas Holmes has found a third way, the point where both touch, not collide, but touch. This haunted land full of the shadows of marks made by man in the earth, of reflections in water and flooded fields, of gardens and seasons changing, is one that is often missed by the passer-by and artist alike, but it is a rich and rewarding place. It is an inspirational well of harmony and balance, as well as of conflict and division. Something shared and something complementary, as she says herself:

We have an intimate relationship with the land, but equally share common connection.

Cas helps others to search and explore the world of the found and the displaced, the cast aside, or perhaps just the mislaid. It is a rich vein of potential and a revelation of connections between our human world [and] the world we refer to as natural.

(JOHN HOPPER 2014)

I use textiles and found materials with a connection to the things I find interesting when encountered during my daily activities and places visited as part of my working and social life. My Romany grandmother fostered this interest in the reclaimed the often overlooked things found along the sides of a path, road or field. In Romany culture, these things had practical uses: for example willow was made into pegs, and reeds and rushes into baskets. My love of storytelling was inherited from her, and I remember her entertaining me with stories of her childhood travelling.

My father has influenced me too. When I was a schoolgirl, I regularly accompanied him on his walk home from work. He encouraged me to look around and to ask questions about the things we observed on these walks: the plaster decorations above eye level on the medieval buildings in the city streets, the shape of a tree against a winter landscape, or the simple breaking through of the first snowdrops or bluebells in our local wood.

I like to do different, as we say in Norfolk, and find different ways of exploring my ideas. I am still interested in the commonplace, things observed on the edges of our vision, and my connection to cloth as an artist and teacher has enriched my investigations. I spent four years at art college, training in painting and drawing, but soon became involved with the world of stitch. Paradoxically, my own works have since been described as painting with cloth. I work without defined boundaries, cutting, tearing, painting and sewing cloth as I trace a personal response to the historical, environmental and social heritage of a place and create new meanings within my work.

A social fabric

The Butler-Bowden Cope c.1330, Victoria and Albert Museum.

Textiles are the social fabric of our cultural history. Everyday stitched textiles for domestic use, where they have survived, remind us of our family connections. Some of us still use items that have been handed down. Historical pieces housed in museums and National Trust collections, from the richly embroidered gowns of the wealthy to the textile hangings for walls and beds, reflect our shared history and remind us of the significance and value of textiles as a symbol of status, comfort and wealth.

The idea that cloth and stitch can be used to communicate a story is not new. Surviving examples of Opus Anglicanum (English work) embroidery, which were mostly designed for liturgical use in the form of copes and vestments, described narratives from the Bible in visual form. These exquisite and expensive pieces of medieval embroidery, of which few survive, contained complex decorative motifs such as flowers, animals, birds, beasts and angels, as well as figures of the saints and biblical characters, all heavily embroidered in gold and silver thread and rich silks. Such was the importance of this art form in medieval England that BBC4 dedicated an hour of prime-time television to a discussion on Opus Anglicanum. In his introduction the programme, presenter Dan Jones (2013) described the quality of stitch in the Butler-Bowden Cope housed in the collection at the Victoria and Albert Museum: It is almost as if this whole piece has been signed with a needle This is from England , and further comments: The English elevated the craft of embroidery into an art of stunning realism and emotion.

The use of stitch remains at the centre of our lives today. At the same time as the referendum was being held over the question of Scottish independence in 2014, the Great Tapestry of Scotland was being exhibited in the Scottish Parliament buildings. The brainchild of the author Alexander McCall Smith and historian Alistair Moffat, the tapestry was designed by Andrew Crummy and work on its illustrated panels was carried out by over 1,000 volunteer embroiderers in one of Scotlands largest community projects. It follows in a grand tradition of stitching narratives: the Bayeux Tapestry, depicting the conquest of England by William Duke of Normandy in 1066 at the Battle of Hastings, is the most well known of the genre.

Artists continue to use cloth for reasons beyond its practical qualities. It ties us to the past and reflects upon the present. Sue Prichard, curator of textiles at the Victoria and Albert Museum, talks about this intimacy and the intriguing relationship she has had with cloth since childhood, when her grandmother taught her to knit and sew:

Domestic textiles are very important to me. My first sewing box was made of cheap, brightly coloured cardboard but I loved that box with a passion and it was the first thing I turned to when I arrived home from school. I made table mats, chair-back covers, needle cases, pincushions all from scraps and mostly from my grandmothers fabric stash. I would gift these items to various members of my family, but nobody appreciated them as much as my grandmother. She worked as a domestic cleaner in a large house in Chelsea as well as running her own home, but always took pleasure in sitting down at the end of the day with her needle. My life differs from my grandmothers on so many levels; however, I always find time to connect to my past. Now I have many sewing boxes in the sitting room, bedroom and kitchen all filled with my grandmothers needles, pincushions, scissors and hundreds of buttons, all recycled and kept for a rainy day.