Slow Stitch

Slow Stitch

Mindful and contemplative textile art

Claire Wellesley-Smith

Contents

Introduction

The speed at which we do something anything changes our experience of it.

The Tyranny of Email, John Freeman

This book explores a slow approach to stitching on cloth. The pleasures to be had from slowing down processes are multiple, with connections to ideas of sustainability, simplicity, reflection and multicultural textile traditions.

The idea of a Slow Movement has been applied to many things, but all look at slowing the pace of life and making a deliberate decision to do so. It is a philosophy that embraces local distinctions and seasonal rhythms, and one that encourages thinking time. In craft terms, I see a slow approach as a celebration of process; work that has reflection at its heart and skill that takes time to learn. By slowing down my own textile practice, I have developed a deeper emotional commitment to it, to the themes I am exploring, and to the processes I use. In the community-based stitching projects I run I have noticed the benefits that this way of working can give to participants. Simple, contemplative activities can be convivial too, creating non-verbal conversations through making.

The scope of textile art is huge. There are always new things to try, techniques to learn and products to buy. While it can be difficult to step away from diverting new experiences, self-imposed limits can bring a meaningful and thoughtful approach to your textile practice.

This book uses simple stitching techniques and traditional practices. It looks at choosing to use re-purposed materials and minimal equipment, and explores slow processes that allow thinking time and create a real connection with the object you are making. It has project suggestions and resources that will help towards making a more sustainable textile practice, and has examples of inspirational work from textile artists who work in this way.

You may find in using this approach that less is more, and that your slow textile projects become more personal and sustainable.

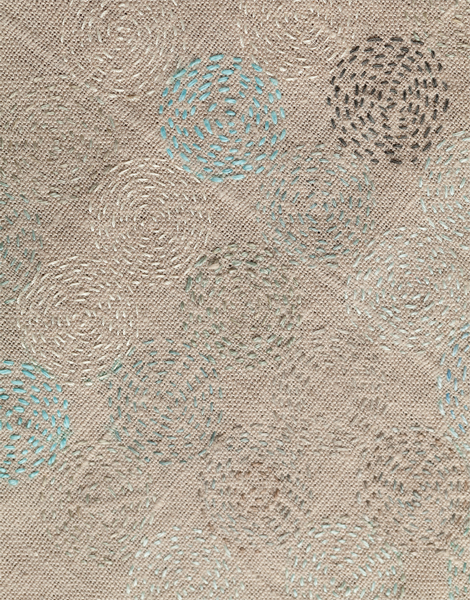

Slow Square (2014). Naturally dyed threads on linen (40 x 40cm / 15 x 15in).

About me

I have come to this slow approach to textiles through a non-conventional route. I studied political science and had a career in community engagement and advice work for many years, often working with people who were experiencing crisis in their lives.

I grew up in a household in which things were made; my mother was a wonderful seamstress and knitter, a textile project always on the go, and she passed her skills to me. My grandmother was a professional machinist and dressmaker, who worked from the age of fourteen to help support her family. In my family, talking was mostly done when accompanied by making. I watched my grandmother knit a jumper for me as a student, fully engaged in all the conversation in the room and simultaneously completing a newspaper crossword. When I went to college to do creative textile courses as a new mother, I started to see connections between my own stitching and making, that of my female relatives, and in the communal support shared by my peers in the classroom. Gradually this developed into my main work, still based in community engagement but nowadays through my textile and teaching practice. My strongest interest is in connections: how do we connect to each other and how does the universality of textiles help us to do this? My approach includes archive-based research looking at the social history of textiles; exploring family stories through textiles and working on projects that aid understanding of personal and community history through textile making. The thread that pulls this together is a strong belief in the process, and I believe that the slower this process is, the more beneficial it can be both for individuals and communities.

The view from my studio.

.

What is the Slow Movement and how does it relate to textiles?

The origins of the Slow Movement can be traced back to the mid-1980s and the beginnings of the Slow Food Movement in Italy, started by Carlo Petrini. This began as a protest against multi-national fast-food companies and became a concerted campaign that encouraged sustainable local production, awareness of heritage, and strong connections to local culture and community. Carl Honors 2004 book In Praise of Slow broadened out these concerns, defining the Slow Movement as a cultural revolution against the notion that faster is always better. In the book he writes, The Slow Movement is not about doing everything at a snails pace. Nor is it a Luddite attempt to drag the whole planet back to some pre-industrial utopia [...] The Slow philosophy can be summed up in a single word: balance [...] Seek to live at what musicians call the tempo giusto the right speed. And on his website Honor goes on to explain, Its about seeking to do everything at the right speed. Savouring the hours and minutes rather than just counting them. Doing everything as well as possible, instead of as fast as possible. Its about quality over quantity in everything from work to food to parenting. The Slow Food Movement has led to other Slow movements, including Slow Cities, aiming to encourage calm living places attentive to residents needs and quality of life, and Slow Fashion, described by Kate Fletcher in her book Sustainable Fashion and Textiles as being about designing, producing, consuming and living better. In the US, the idea of Slow Cloth has been expounded by Elaine Lipson, an artist and writer with a background in the organic-food movement, who linked the principles of the Slow Food Movement into a manifesto for textile making in her Slow Cloth Manifesto article, published in Textiles and Politics: Textile Society of America 13th Biennial Symposium Proceedings in 2012 and also online at digitalcommons.unl.edu.

Field Work (Yellow) (2012). Naturally dyed and pieced using repetitive hand stitching (35 x 15cm / 13 x 6in).

The speed of life in the 21st century can often be overwhelming. Life is relentlessly busy, but this is not a new phenomenon. In 1875, W.R. Greg wrote an article called Life at High Pressure, much quoted at the time, bemoaning a life lived so full [...] that we have no time to reflect where we have been and whither we intend to go. Around the same time, William Morris and makers within the Arts and Crafts Movement were consciously returning to pre-industrial processes, including the use of natural dyes and handloom weaving, despite the wide availability of faster, modern alternatives.