introduction

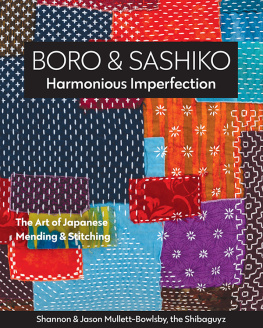

My interest in boro began in 1991 when I was an English teacher in northern Japan. The owner of the local antique shop gave me a bag of unsellable old clothing, saying that it might do for patchwork. This included a work jacket about ninety years old, with a small boro repair on the front. I was touched by the care someone had taken to repair the fabric before making something new. I didnt cut it up! I began looking for other pieces, finding out more about boro and its many enthusiasts today.

The Japanese wordboro,meaning rag, has become a popular term among international textile artists over the last twenty years or so. It is most often associated with clothing and household textiles that were pieced from recycled scraps and repeatedly patched as they were used, worn out and became ragged. The original boro items were made from necessity, by people in poor and remote regions where raw materials for new textiles were scarce and expensive. While some antique pieces include simple sashiko, boro is not a style of sashiko stitching. It is the embodiment of another currently popular Japanese term,mottainai(dont waste!).

Nowadays, vintage boro is admired for its subtle colours and ragged textures, the abstract art effect of the patches and the enduring warmth of a unique handmade textile. Antique boro is becoming expensive and good examples are scarce, partly due to the interest of collectors but also because a lot of boro was simply used up, worn out or thrown away. It is a finite resource.

Inspired by these original boro pieces, many people want to make their own. The good news is that this is not difficult: it needs relatively few resources other than fabric scraps, needle and threads; no special skills are required; and there are almost no rules, other than an appreciation of original boro. With the passage of time, from everyday wear and tear, new creations will start to acquire a similar patina to old boro, too.

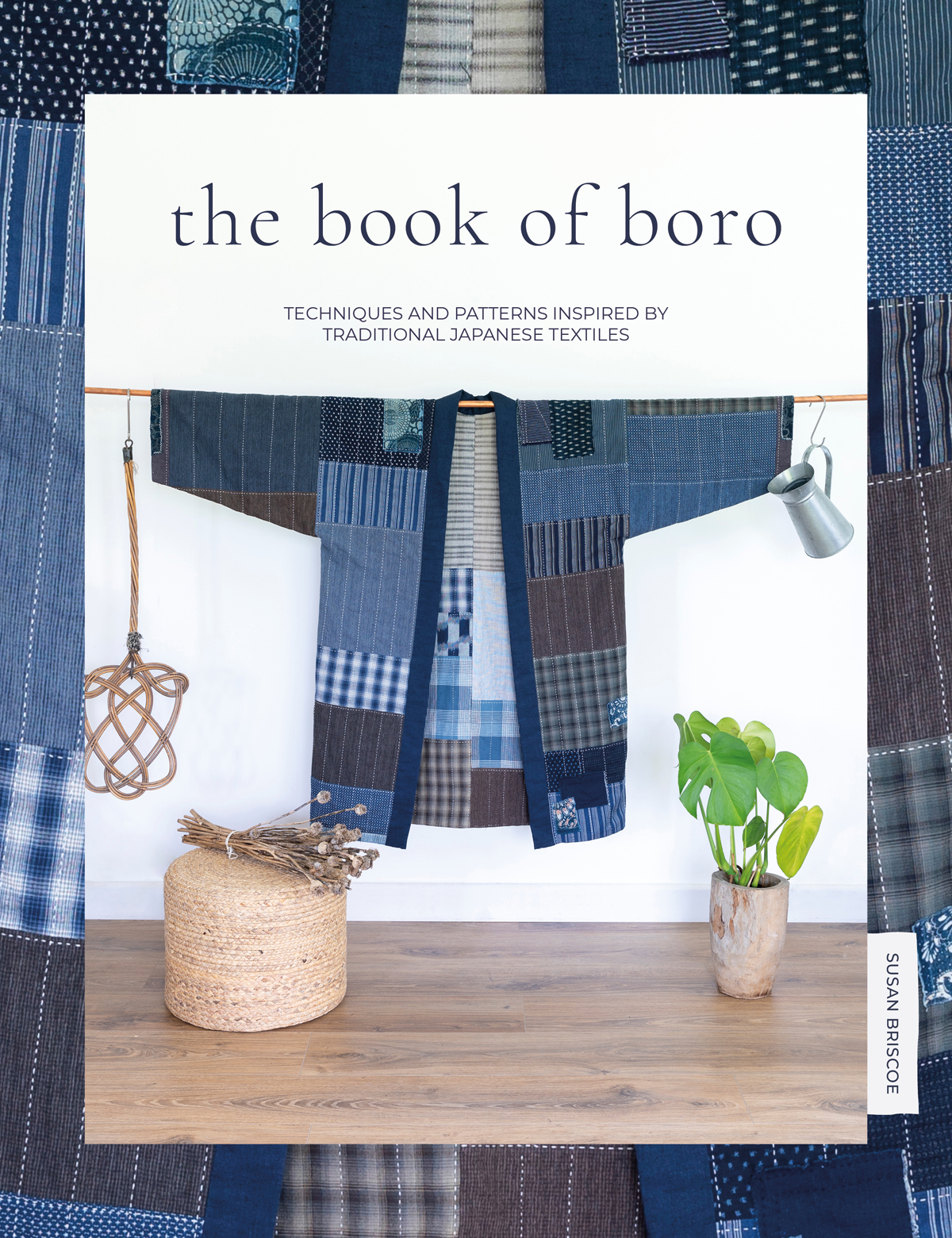

This book includes the basic techniques you need to create your own boro-inspired items, with a selection of projects large and small to get you started, inspired by my collection of antique boro but with a contemporary twist. To make boro patchwork base fabrics more quickly, I have used my sewing machine for piecing, but all visible stitches are made by hand, and, like the originals, these can be quite rough and imperfect at times. Boro techniques can also be used to repair existing items, such as jeans andother clothing.

Contemporary trends such as visible mending and slow stitch have embraced boro, although nowadays we are rarely stitching from necessity. Boro is ideal for showcasing treasured fabric scraps, reflecting ecological and sustainability issues. Its patina of time is harder to achieve instantly and is best gained through everyday use, but simple breakdown techniques can accelerate wear. Perhaps we can never simply make boro on demand it needs time and use to truly become boro. Make it, use it, love it.

boro history

Once something becomes the fabric of our memories, it moves from the material to the non-material in its importance. It becomes hard to part with.

Sheila Cliffe, Japanese textile researcher and kimono stylist

the meaning of boro

The kanji characters forboroalso read asranru, meaning rag, scrap, tattered clothes, a defect, run-down or shabby. While it has connotations of worthlessness and junk, to its original makersboromono(literally rag thing), as it is sometimes called, represented a desire to lovingly clothe their families and keep them warm in very harsh environments, such as the remote farming areas of northern Japan. It was an everyday repair. They couldnt afford or access new fabric, so they used recycled cloth to make what they needed. Piecing, stitching and mending were once widespread throughout Japan, but remained important for longer in areas where new fabrics were not manufactured so were scarce and expensive. Layers of patches, worn and torn, created a random,tactile beauty.

The inside of this ragged, unlined hanten noragi (half wear work jacket) with makisode (wrapped sleeves) has raw-edge, heavily darned patches in shades of indigo. Tohoku, c.1900.

the second-hand cloth trade

Cotton cannot be grown in northern Tohoku, on Japans main island, where winter is cold and long and the hot summer too short. Grown commercially in Japan since the 1600s, first as a luxury fibre, it was cultivated south of the Aizu region by the early nineteenth century and traded second hand around Japan. Before mechanized spinning and weaving, second-hand fabric was valuable. The far north of Tohoku and the western coast were supplied by sea via theKitamaesen(north front route), linking the Kansai region (around Kyoto) with the northwestern coast of Tohoku. Ships travelled the route once a year, leaving Osaka at the beginning of April, and traded all along the coast as far as Hokkaido.

Generally,kimono(which simply means wearing thing) are modular garments, made from a series of rectangles with no shaping, so recycling is easy. Even the V-shaped front opening, where the long collar is attached diagonally, is not cut, and the fabric is folded into the collar to give extra bulk and body. One kimono uses one whole bolt of narrow cloth (), approximately 1315in (3538cm) wide and 3638ft (1111.6m) long, sewn with a centre back seam. Simple shapes can be unpicked and the fabric pieces rearranged to even out wear, the back becoming the front or the sleeves wrist opening being reattached to the body. Unpicked for washing and resewn, kimono fabric must have been frequently turned. Removable, washable collar covers, often made from black sateen, were sewn on to protect the kimono collar from wear and to prevent stains from hair oil (used to fix the elaborate hairstyles of the Edo era [16051868]). The collar cover can still be seen today on all kimono, but now usually matches. One exception to the collar shaping seems to have been paddednoragi(work wear), such asdonzajackets, where the V-shape was cut, perhaps to eke outthe fabric or reduce bulk from the wadding (batting).

In rural Aomori prefecture, while prosperous local landowners could buy a whole second-hand cotton kimono, poorer villagers could only affordtsugi(scraps). Five or six women would club together to buy a 4852lb (2224kg) bale of second-hand cloth from itinerant traders. They washed the dirty, damaged rags in lye, removing the worst of the grime by scrubbing with rough fish skins, and starched the scraps with rice water before grading them. The fabrics bore the marks of previous use, such as worn collar edges. While the worst of the scraps were torn into narrow strips to make