Contents

Guide

Publisher: Amy Barrett-Daffin

Creative Director: Gailen Runge

Acquisitions Editor: Roxane Cerda

Managing Editor: Liz Aneloski

Editor: Karla Menaugh

Technical Editor: Debbie Rodgers

Cover/Book Designer: April Mostek

Production Coordinator: Tim Manibusan

Production Editor: Jennifer Warren

Illustrator: Valyrie Gillum

Photo Assistants: Kaeley Hammond and Lauren Herberg

Instructional photography by Jason Mullett-Bowlsby; lifestyle and subjects photography by Estefany Gonzalez of C&T Publishing, Inc., unless otherwise noted

Published by Stash Books, an imprint of C&T Publishing, Inc., P.O. Box 456, Lafayette, CA 94549

Dedication

TO ANOREE KAY BRUNER-BOWLSBY, ALSO KNOWN AS MOM

As a lifelong maker, you always cheered us on and celebrated our accomplishments in the fiber arts. When we found out we were going to be writing a sewing book, you were the first one we wanted to call.

We hope we did you proud.

J & S

Acknowledgments

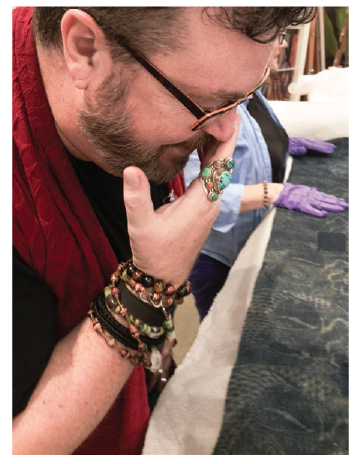

SEATTLE ART MUSEUMWe are eternally grateful to the folx at the Seattle Art Museum, particularly Elisabeth Smith (Collection and Provenance Associate) and Marta Pinto-Llorca (Senior Collections Care Manager). Thank you for having faith in our vision and for giving us supervised access to study the pristine pieces that allowed us to confirm our theories and learn amazing new things about boro and sashiko.

ROLAND CRAWFORDANCIENT GROUNDSSpecial thanks to our new friend for sharing part of his epic boro collection. His generosity gave us a deeper understanding of the imperfect beauty and genius of centuries-old boro. A visit to his coffee shop in Seattle, Ancient Grounds, is a rabbit hole into history and he makes a mean latte (just sayin!).

CHRISTINE C.You were our eyes and ears in Japan. We cant thank you enough for sourcing thread, thimbles, needles, and thread snips for us to compare to our United States tools. And the books you brought back were true treasures.

RESOURCESThank you to the following companies, which generously provided products for use in the creation of this book: Aurifil, BERNINA of America, Clover Needlecraft, Reliable Corporation, Cherrywood Fabrics, Marcus Fabrics, Michael Miller Fabrics, RJR Fabrics, and Robert Kaufman Fabrics.

THOSE WHO CAME BEFORE USWe thank those whose hands created the work that inspired us. Their work, created from necessity, now inspires scores of crafters to emulate and reawaken this art form. We hope our efforts to carry on and translate their work honor their existence and their lives.

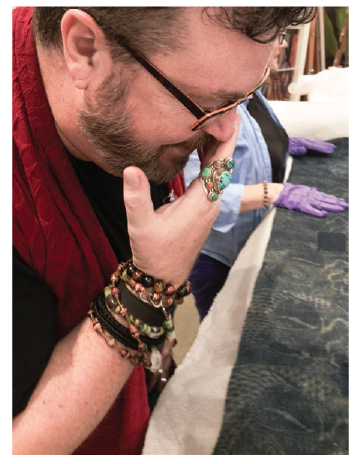

Shannon examining a garment at the Seattle Art Museum

INTRODUCTION

Time Travel Through Fabric, Craft, and ArtWelcome to the Rabbit Hole

We are rabbit-hole people. We love research and finding out the story behind things. We get a thought in our heads or come across an idea, and the next thing you know there are 120 browser windows open on several devices and weve checked out every book and downloaded every documentary on the subject. No subject is too great or too small that we wont dive right down that rabbit hole until our curiosity is satisfied. Sometimes that takes minutes; sometimes it takes days or years.

Our journey in boro and sashiko started innocently enough while researching patchwork and handwork techniques that didnt require much equipment and, ideally, would be completely portable. In the hopes that we could develop future classes that would inspire others to do more handwork, we began to build on our own skills of hand sewing, hand-pieced quilting, and English paper piecing.

As one does when one is going down a rabbit hole, we took a random turn. This new path led us to the history of crazy quiltssomething we were familiar with from family members who had made at least one of these glorious quilts. But where that turn lead to was completely unexpected. And wonderful.

Always focused on the context of the content (the heart that beats within the chest of every rabbit-hole person), we researched the origins of crazy quilts, which lead us to stumble onto an article with a vague reference to the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition of 1876 and a display from the newly opened Japan that included repaired pottery and textiles. Another browser window and search-engine inquiry resulted in historical documents that referenced these patched and repaired textiles and pottery as the impetus for the crazy quilts movement of the late nineteenth century. Patched Japanese textilesthat sounded interesting! We wanted to see where that went.

Several more browser tabs and there it was on our computer screen: the front page of the Amuse Museum in Japan with its permanent exhibit of boro pieces collected by Chuzaburo Tanaka. We had never seen boro or sashiko textiles before, but here they were in all their unassuming glory. Each piece was tattered and patched and adorned with elaborate stitching, all done by hand for the purpose of strengthening and repairing the fabrics. They were glorious!

Even more deep dives and hundreds of books and web pages later, we found ourselves utterly consumed with how the boro and sashiko techniques were closely tied to hand stitching and repairing techniques from all over the world, including those from our own backgrounds. This was all new and exciting but strangely familiar and comfortable. We found ourselves remembering patched blankets and clothes from our childhoods. And even as recently as 25 years ago, as a younger married couple, we remembered patching up work clothes to make them last longer because we couldnt afford to buy new ones.

As we studied the textiles in person in private collections and in the archives of the Seattle Art Museum, and our hands practiced the stitching techniques (this was literally not our grandmothers running stitch), we delved deeper into the world of the Japanese people who created these pieces. What were their lives like that they, over the course of lifetimes, were required to patch garments and blankets and hand them down, each generation making subsequent patches and repairs? Why were these textiles created in the first place? The answers spurred a deeper obsession for boro and sashikoa love that has led us to learn more and seek out instructors and collectors from whom we can continue to learn.

A large textile panel with boro patches being examined by staff at the Seattle Art Museum

These techniqueswhich started from a utilitarian practice, dire necessity, and destitutionhave, through the passage of time, become art. Like looking at our grandmas and great-grandmas quilts and handwork pieces, looking at these boro pieces transports us back to a time and place that seems surreal in the context of our relatively comfortable lives. We have a difficult time fathoming the daily life of these people who first laid hands on this fabric. Who were they? What were they thinking about when making these stitches? Did they quietly sing songs to themselves like we do when we work in our studios? This connection with the original makers and their lives, their worlds, this is the transportive nature of studying these textiles from another place and time.