Connect with Diversion Books

Connect with us for information on new titles and authors from Diversion Books, free excerpts, special promotions, contests, and more:

@DiversionBooks

www.Facebook.com/DiversionBooks

Diversion Books eNewsletter

Copyright

Diversion Books

A Division of Diversion Publishing Corp.

443 Park Avenue South, Suite 1008

New York, NY 10016

www.DiversionBooks.com

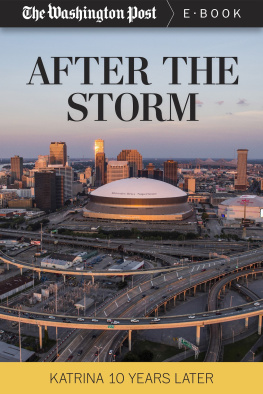

Copyright 2015 by The Washington Post

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever.

For more information, email

First Diversion Books edition September 2015

ISBN: 978-1-68230-134-0

Introduction

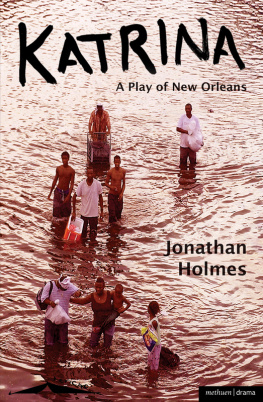

When Hurricane Katrina hit the Gulf Coast on Aug. 29, 2005, it wrenched more than a million people from their homes and nearly washed away one of the countrys most distinctive cultural capitals, New Orleans. The killer storm forever reordered the citys economy and population and soul in ways that are still being felt today. What changed? What was gained? What was lost in the wake of the monster storm that hit 10 years ago?

Dozens of Washington Post writers and photographers descended on New Orleans when Katrina hit, and many of those same journalists went back for the anniversary, trying to take the full measure of the citys long, troubled, inspiring, unfinished comeback.

What they found was a thriving city, reassured by a new $14.5 billion complex of sea walls, levees, pump stations and outfall canals. What they heard was that, w hile some mourn the loss of the New Orleans soul and authenticity, otherswho saw a desperate need for improvement even before the stormwelcome the rebuilding of New Orleans into Americas latest tech hub.

The city has emerged as a symbol of resilience, an inspiration for other places savaged by natures whims and mans mistakes. Its problems have made it a magnet for the worlds tinkerers, thinkers and doers.

As a result, New Orleans has become Americas latest, great laboratory of social engineering. The flood was chased by a second flood of peopleincluding the likes of Brad Pitt and Oprah Winfreywho wanted to come to New Orleans to save the world. And as they remade the city, the city remade them.

But New Orleans is still a fragile place, the recovery a work in progress even after 10 years.

The New Orleans East, the predominately African American residential division of the city, has yet to return to a habitable place as it was not a priority to rebuild after the storm.

In some places in the Eastdown in the Lower 9th Ward, in Desirethe shells of houses wrecked by Katrina still rot in the humidity, caved-in roofs and teetering walls sharing the same blocks with homes that got put back together, lifted onto concrete stilts and re-inhabited.

Any story about Katrina is also the story of the many people who abandoned the coast as well. New Orleans lost some 100,000 residents, most of them black. A family of six living near a levee that broke ended up at a Red Roof inn outside Houston, and then from there, Nebraska. Auburn, Neb., population 3,000. Ten years later, theyre still there, in a little apartment complex, behind on rent.

And after 10 years, theres still a sense that the worst is yet to come, that the city is an Atlantis-in-waiting.

Katrina was not the big one; after all. It dealt the city only a glancing blow. In the long term, New Orleanss safety depends on far more than walls. An ambitious plan to restore the vast wetlands along the coast that protect the city from flood is a ways off from being realized, and may never be.

In an era of climate change, with sea waters rising and storm surges growing even more destructive, many people wonder whether a city that lies half below sea level can even survive.

This e-book, then, is both a backward and forward look at New Orleans comeback, full of the voices of those who were pushed by Katrinas winds in directions they never imagined.

The city, on balance, is far better off than before Katrina, says Jason Berry, a prolific New Orleans author. But its still a break-your-heart kind of town.

Chapter One:

The Resilience Lab

By Manuel Roig-Franzia

Photos by Ricky Carioti, Jabin Botsford

NEW ORLEANS -On the "sliver by the river," that stretch of precious high ground snug against the Mississippi, tech companies sprout in gleaming towers, swelling with 20-somethings from New England or the Plains who saw the floods only in pictures.

A new $1 billion medical center rises downtown, tourism has rebounded, the music and restaurant scenes are sizzling, and the economy has been buoyed by billions of federal dollars.

The city is now swaddled in 133 miles of sturdier levees and floodwalls, and it boasts of the world's biggest drainage pumping station. But on the porch stoops of this place so fascinated by and so comfortable with the cycles of death and decay, they still talk about living in some kind of Atlantis-in-waiting. As if the cradle of jazz might still slip beneath the sea.

The sliver by the river seen across the Mississippi from Algiers, foreground has become a hive of activity since Katrina. Farther out, the picture is more mixed in the citys lower-lying neighborhoods.

Ten years after Hurricane Katrina made landfall in New Orleans on Aug. 29, 2005, newcomers take their juice with chia seeds and buy fixer-uppers, and longtime locals fret that the city is no longer theirs, that it's too expensive and still might lose its soul. A city some feared might be left for dead when 80 percent of its footprint was submerged in floodwaters on that day, is undergoing a social, economic and cultural evolution. Yet it is still a place deeply tied to its ancient traditions and rites, stubbornly and proudly unique, unparalleled in its embrace of the weird, the mysterious, the whimsical.

Most folks know someone who couldn't get back to this city or has been pushed outside its bounds these are the ghosts that don't star in the moonlight tours, the ghosts of not-so-long-ago neighbors. And it doesn't take much to get people weeping or boiling with rage about that other New Orleans, beyond the resurrected city center, where gunshots form the nighttime soundtrack.

The mayor gathers before-and-after photos of murder victims, images of too-short lives and bloodied ends, in a tumbling and ever-spreading row of red binders on the floor of a corner in his office.

The other New Orleans reveals itself once you descend from the dry heights by the river, down into the neighborhoods that were swamp when the French arrived 300 years ago, and that seem fatally determined to return to that state-of-being whenever a storm blows up.

In the Lower Ninth Ward, in Desire and out in eastern New Orleans, the shells of houses wrecked by Katrina still rot in the humidity, caved-in roofs and teetering walls sharing the same blocks with homes that got put back together, lifted onto concrete stilts and reinhabited.

Yet the city's very survival as an inviting and vibrant space has made it into a symbol of resilience, an inspiration for other places savaged by nature's whims and man's mistakes. And the intractability of some its problems in some cases problems that existed before the storm, but have worsened or stagnated since have made it a magnet for the world's tinkerers, thinkers and doers.

@DiversionBooks

@DiversionBooks www.Facebook.com/DiversionBooks

www.Facebook.com/DiversionBooks Diversion Books eNewsletter

Diversion Books eNewsletter