Merrie

England

A Journey through the Shire

Joseph Pearce

TAN Books

Charlotte, North Carolina

Merrie England copyright 2016 by Joseph Pearce.

All rights reserved. With the exception of short excerpts used in articles and critical reviews, no part of this work may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in any form whatsoever, printed or electronic, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Cover and interior design by David Ferris.

ISBN: 978-1-5051-0719-7

Cataloging-in-Publication data on file with the Library of Congress.

Published in the United States by

TAN Books

P.O. Box 410487

Charlotte, NC 28241

www.TANBooks.com

Printed and bound in the United States of America.

For

the ghosts of Englands past

who accompanied me on the journey

THEY called Thee MERRY ENGLAND, in old time;

A happy people won for thee that name

With envy heard in many a distant clime;

And, spite of change, for me thou keepst the same

Endearing title, a responsive chime

To the hearts fond belief; though some there are

Whose sterner judgments deem that word a snare

For inattentive Fancy, like the lime

Which foolish birds are caught with. Can, I ask,

This face of rural beauty be a mask

For discontent, and poverty, and crime;

These spreading towns a cloak for lawless will?

Forbid it, Heaven!and MERRY ENGLAND still

Shall be thy rightful name, in prose and rhyme!

William Wordsworth

Contents

T he journey on which you are about to accompany me is a voyage into the mysterious presence of an England that is more real than the one that you are probably accustomed to seeing. It is not the England that presents itself to the unenchanted eye, the England that seems to be in terminal decline, its death throes made manifest in the all too obvious signs of decay and ultimate disintegration. It is, in stark contrast to this mutable England, an enchanted and unchanging place, full of ghosts who are as alive as the saints. It is an England that is rural, sacramental, liturgical, local, beautiful an England that is charged with the grandeur of God.

This England, partaking of the divine essence from which it receives its being, shines forth the mysterious paradox that a thing both is and was at the same time. We can take almost any example to illustrate this paradoxical mystery, but lets take the case of Shakespeare. Like the England that gave him birth, Shakespeare both is and was. He was a great playwright and poet, but it is also true to say that he is a great playwright and poet. Shakespeare is a fact. He lived and did things. In this sense, he not only was but is. You cannot look at the history of England or of great literature without looking at Shakespeare. He is staring you in the face because his presence is realand his presence is present. He is as well as was.

In order to understand this more fully, we need to understand the relationship of time to eternity. With our finite perception, we can perceive only the past. Even the present, by the time that we perceive it, has become the immediate past. The future, on the other hand, can only be a figment of our imagination. It is what might happen. The nearer the future is to us, the more predictable it might be. I might intend to go to a caf for a coffee this morning, and in all probability I shall do so. The further the future is from us, the less predictable it becomes. I cant even be sure of the place in which Ill be living five years from now. Indeed I cant even be sure that Ill be living.

For God, however, there is no past and there is no future. For God, everything is present. This is the deeper meaning of divine omnipresencenot that God is present everywhere, though He is, but that everything is present to God. For God, therefore, we cannot say that Shakespeare was, but only that he is.

Where is all this leading? Well, in the case of England, we must insist that England is eternally greater than those who happen to be wandering around today on the geographical stage on which the drama of England is being performed. Most people walking around on the stage today have no idea what England is or who they themselves are. Thankfully, however, England is not dependent on them. Like the souls in C. S. Lewiss The Great Divorce, they are pathetic shadows of who they are meant to be. They are relatively insubstantial. They are certainly less real as Englishmen than Alfred the Great, Bede the Venerable, St. Edward the Confessor, Chaucer, St. Thomas More, the hundreds of English martyrs, Shakespeare, Austen, Newman, or Tolkien. All of these people are England. Please note: They are England.

Seeing the true England through the perspective of the Triune splendour of the Good, the True, and the Beautiful, we know that such an England can never dienot because it lingers like a fading coal in the memory of mortal men, but because it exists as a beautiful flower in the gardens of eternity. This is the England to which, under God, I owe my allegiance. Deo gratias! And this is the England through which I wander in the following pages, and to which you are invited to join me.

A Note

On Lost Time

W hat follows was written at the turn of the present millennium. Any apparent anomalies with regard to dates are explained by the time lost between its being written and its being read.

_____________

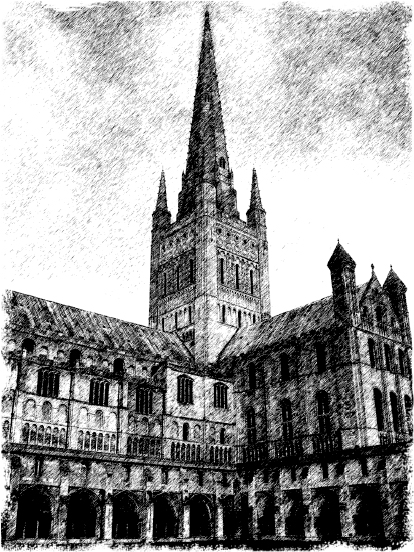

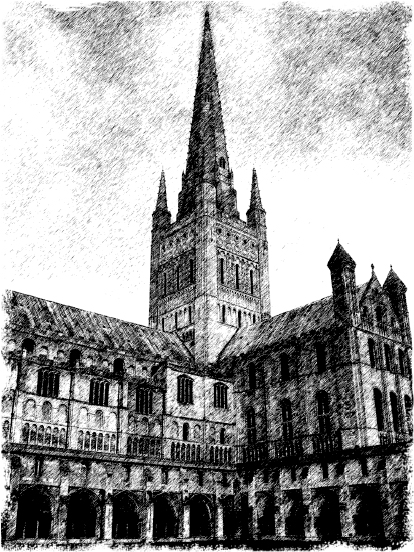

Norwich Cathedral

Norwich

Cathedral

T he romance of Gothic architecture was brought to life for me by G. K. Chesterton. Quite literally brought to life. In prose prophetic and profound, he had written of an optical illusion caused by a stationary furniture van parked in front of a cathedral spire; when the van moved off, it appeared for a moment that the spire, and not the van, was moving. This was the inspiration for an essay in which Chesterton imagined the great Gothic cathedrals and churches of Christendom marching across Europe, spreading the Faith they symbolised. Never again could I look upon church architecture without this poignant imagery imposing itself. Every morning, walking to work, the spire of Norwich Cathedral moving behind the rooftops conjured images of the Church Militant on the march, the spire pointing heavenwards a permanent reminder of the Church Triumphant. Yet, in spite of this, I had resisted the temptation to investigate the cathedral more closely. I was afraid if I looked upon her magnificence, the magic would pass and she would once more turn to stone. I was scared she would be petrified.

And if I was expecting to be disappointed, I was not to be disappointed. A feeling of anticlimax overcame me as I crossed her threshold. Along the walls were no statues of her saints, stone symbols of centuries of sanctity and service to her spouse. Instead, her walls had been sold as advertising space to wealthy parishioners. Similarly, the holy relics of those who had given their lives for the Faith had long since been purged in some puritanical pogrom. The area originally set aside for them had become a repository for antique silver, unholy relics one was asked to deposit fifty pieces of silver for the privilege of seeing. Neither was this the only snub against Gods saints. Directly beneath the bishops throne, the repository for the holy relics lay bare. Above it, a note of derision had been nailed: Directly above this spot is the bishops throne. People once believed that the essences of the holy relics passed up the flue into the bishop above.