Published by

Grub Street

4 Rainham Close

London

SW11 6SS

Copyright Grub Street 2013

Copyright text Richard Pike 2013

A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library

ISBN-13: 9781909166134

EPUB ISBN: 9781909808669

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a

retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission

of the copyright owner.

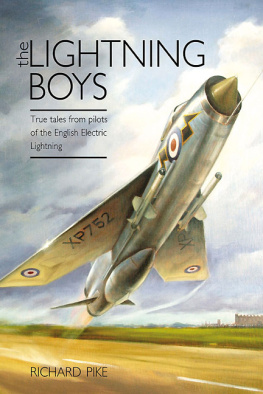

Cover design by Sarah Driver based on a painting by Chris Stone

Formatted by Sarah Driver

Printed and bound by MPG Printgroup Ltd.

Grub Street Publishing only uses

FSC (Forest Stewardship Council) paper for its books.

PUBLISHERS THANKS

To all contributors and, as always, the indefatigable

and ever helpful Ed Durham.

For Marcus, Chloe, Leo, Katie, Charlotte, James, Athena and Emily.

Also in memory of Lily.

CONTENTS

A tribute to Robbie

Squadron Leader J C Robbie Cameron

INTRODUCTION

Submissions for this book have been sent to me in a variety of formats including diary entries, interviews, notes, log book extracts and audio tapes. As in the first Lightning Boys, therefore, every chapter has been written by me although I have used the first person singular throughout and obtained each persons approval before finalising a script. Id like to thank warmly all of those who showed such illuminating co-operation as the book progressed.

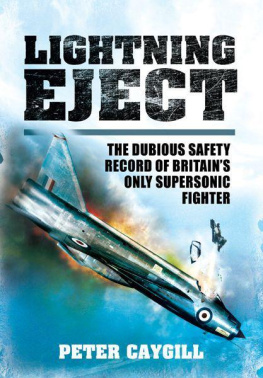

With particular thanks to aviation artist and former Lightning commanding officer Chris Stone who painted the picture on the front jacket cover specially for Lightning Boys 2.

Richard Pike

Aberdeenshire, Scotland 2013

CHAPTER 1

RED ALERT

HOW STEVE GYLES SAVED THE WORLD

It is a truth universally acknowledged that fighter pilots are bold, dedicated individuals of the highest calibre and probity. Despite this general recognition of polymaths with legendary qualities of sophistication, prepossession and perspicacity, some folk may not realise that up there, up at thirty-something thousand odd (sometimes very odd) feet, even a fighter pilot can be left feeling alone and fragile. While, normally, the exhilaration of flying an aircraft such as the Lightning would cause worldly issues to be transcended, situations could arise which might mean that even the finest and fieriest of fighter pilot will be brought down to earth in a most unexpected manner.

Steve Gyles by 11(F) Squadron Lightning Mk 6 fitted with over-wing fuel tanks, March 1970.

Take, for example, the mass arrival in ones vicinity of enemy aircraft in their seemingly endless hordes. When the sky suddenly becomes thick with hostile machinery, when you are outrageously outnumbered and inadequately equipped to do what you are supposed to do, the result is not a happy feeling. I know this because, as happened to the Spitfire and Hurricane pilots in the Battle of Britain, I experienced a similar effect myself some thirty years on from those dark days of 1940. The hollow sensation that strikes the pit of the stomach, the realisation in one awesome, spine-chilling second that you are about to be wholly and dreadfully overwhelmed, is something that has to be gone through to be understood.

As a first tourist at the time, my experience was probably all the more difficult to manage. Recent circumstances had not helped either. Just the previous month, in early March 1970, I had been in the officers mess at RAF Leuchars in Scotland, the base for my squadron (No 11[F]), when the abrupt, eerie shriek of the station crash alarm had caused all to fall silent and to listen out for further details. After a pause, a terse voice on the Tannoy system announced the news of an off-base crash. At once, I dressed quickly (Id been in the bath) and hastened to my squadron operations set-up. There, I learnt that one of our pilots, the squadron weapons instructor, had ejected from his Lightning after a double reheat fire by the Isle of May in the Firth of Forth, north of Edinburgh. There was little we could do at that point except pace the room while we awaited information from the search and rescue services. This was slow in coming and everyone became increasingly concerned as the night wore on.

Our worries were reinforced by thoughts of just a few days before when squadron pilots had been required to attend a briefing on safety drills. While attentive to the drills, nevertheless it was hard sometimes to avoid a sense that such drills were, to a degree, hypothetical a necessary part of training though in reality we might have thought: This isnt going to happen to me no way!

I could recall clearly how, as he had sat on a window ledge that day and as he had stared impatiently outside, our squadron weapons instructor had seemed to reflect that attitude more keenly than most.

This made the situation even more poignant when, finally, we heard that, having survived his ejection, our colleague had died of exposure in the Firth of Forth. He had failed to board his one-man dinghy and a lanyard connecting pilot to dinghy had been found floating in the water some distance away.

Later, we learned some painful facts. Our squadron weapons instructor, we were told, had modified his immersion flying suit by cutting off the watertight, if uncomfortable, rubber boots to replace them with flexible rubber wrist seals. He then had worn ordinary boots and socks socks which hed tucked inside the rubber seals; socks, therefore, which had acted like wicks when immersed in the sea. Under his flying suit he had donned a flimsy T-shirt (hed played a game of squash shortly before flying and consequently had felt hot) thus he had little in the way of thermal insulation. His emergency procedures had been incorrect: instead of activating the SARBE location device he had removed the battery by mistake. Furthermore, his emergency light had been improperly operated as a result of which he had very little illumination and then for a short period only.

Numerous equipment and procedural changes were instituted after this accident. However, of the lessons learned, perhaps the most tragic was the realisation that, if complacency had compounded the various factors which had led to the needless loss of a young, talented life, then not one of us, surely, could claim to be guilt free.

All of this, naturally, was at the forefront of my mind when, the day after the tragedy, I led the first pair of our squadrons Lightnings to fly following the accident. Meanwhile, fire integrity checks were conducted on our aircraft, including those recalled from a detachment to North Wales for missile firing practice. When these checks were completed, another squadron pilot and myself were sent back to North Wales in order to fire off all five of the Red Top air-to-air missiles allocated to the squadron for practice firings. We managed to achieve one firing each before another urgent call ordered us back to Leuchars immediately. Trouble, it seemed, was brewing left, right and centre. The Soviets had decided, evidently, to show off their air power in order to mark the centenary of the birth on 22 April 1870 of their hero Comrade Vladimir Lenin, the gremlin in the Kremlin who, in his time, had managed to out-communist other communists to an amazing extent and who had led the October Revolution of 1917.

From our squadrons perspective, this meant intense periods of duty in the QRA (Quick Reaction Alert) hangar. I was heavily involved, of course, and by mid-April 1970, having completed over half-a-dozen sessions of 24-hour QRA duty during the month, I had begun to feel rather jaded. Aircraft recognition sessions, a regular part of squadron training, featured prominently as we honed our ability to recognise and classify Soviet aircraft. The likes of the four turboprop-engined Tupolev Tu-95, especially the six or seven crew Tu-95 RT version (that veritable icon of the Cold War and code-named Bear D by NATO) and the twin jet-engined Tupolev Tu-16 (code-named Badger) had to be identified from every conceivable angle and under all kinds of lighting conditions.

Next page