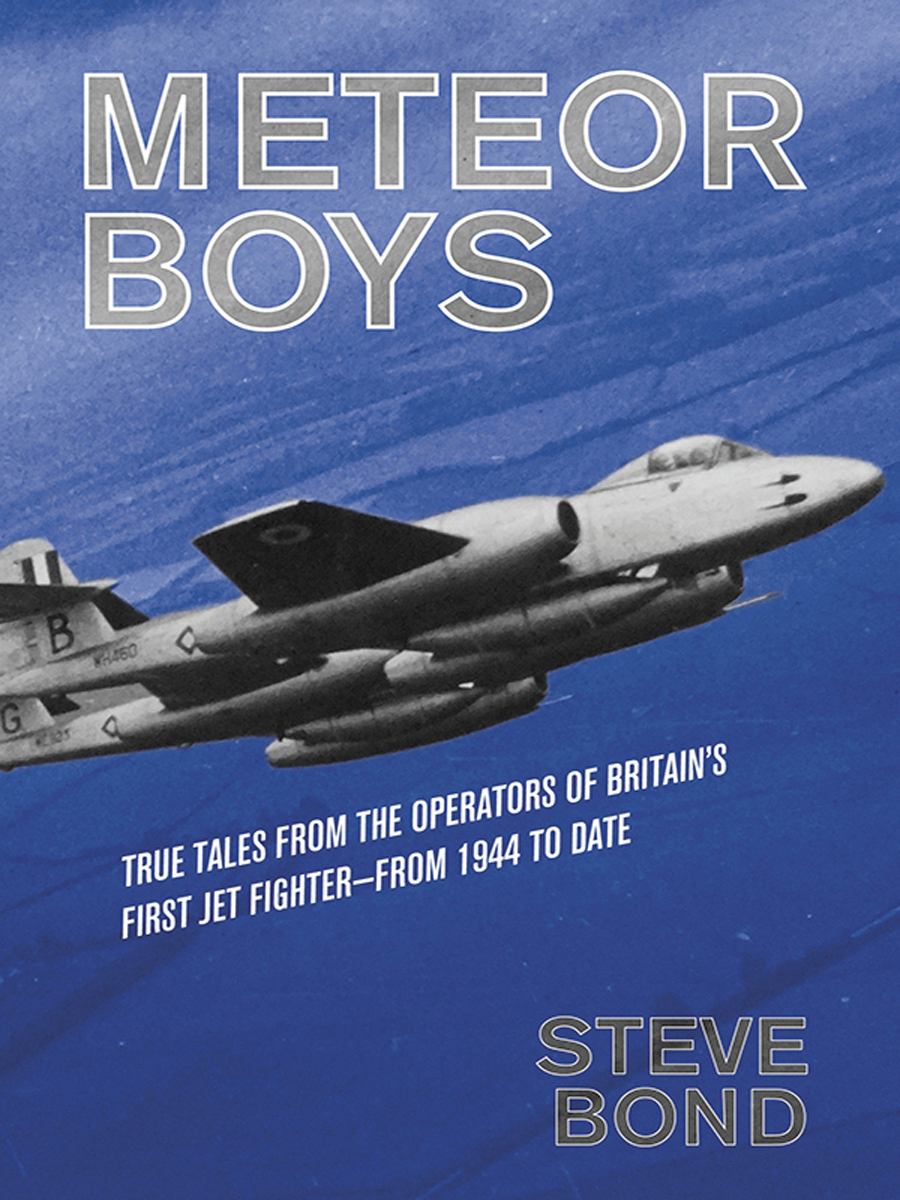

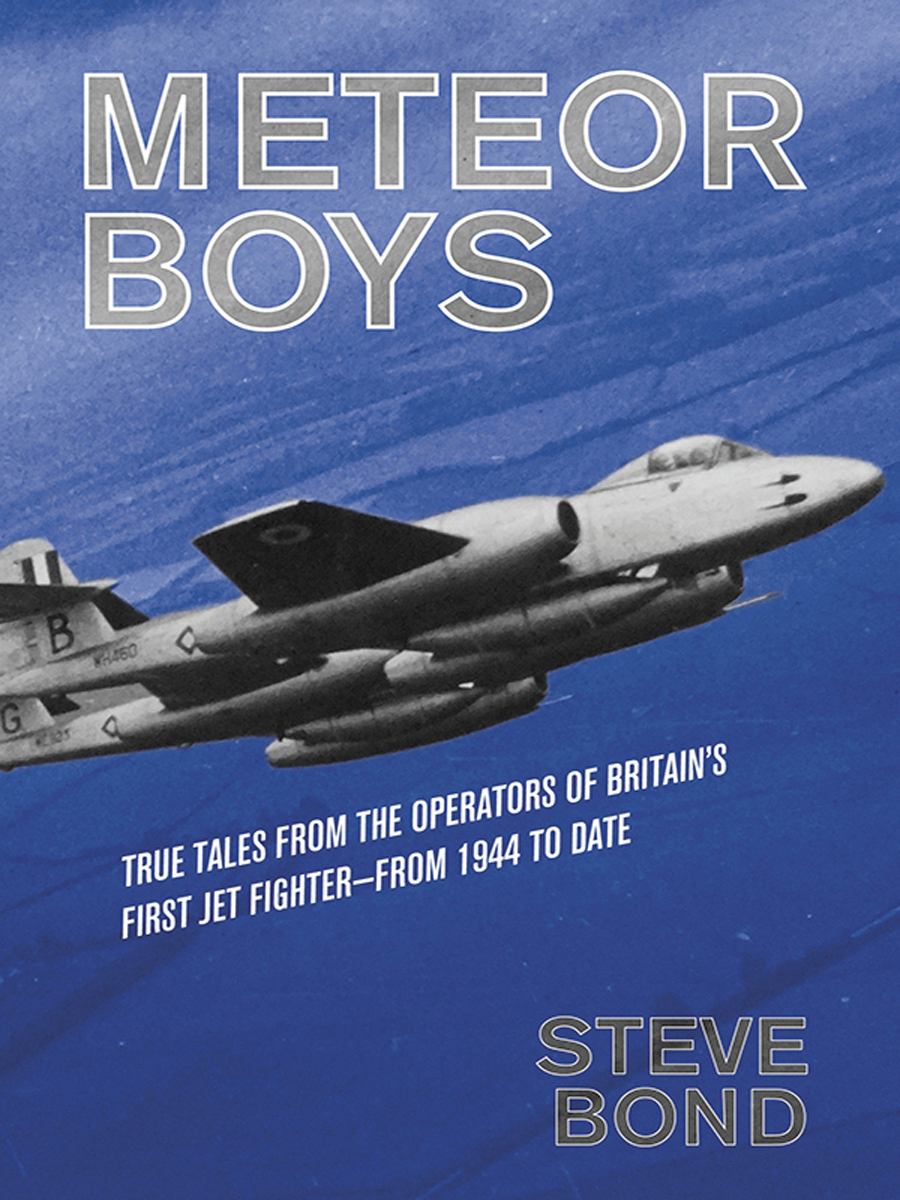

METEOR BOYS

METEOR BOYS

TRUE TALES FROM THE OPERATORS OF BRITAINS FIRST JET FIGHTER FROM 1944 TO DATE

STEVE BOND

GRUB STREET LONDON

Published by

Grub Street

4 Rainham Close

London

SW11 6SS

Copyright Grub Street 2016

Copyright text Steve Bond 2016

A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library

ISBN-13: 978-1-910690-26-0

eISBN-13: 978-1-910690-65-9

Mobi ISBN-13: 978-1-910690-65-9

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner.

DEDICATION

To my darling wife Christine

July 1947 October 2015

Who always encouraged me in my writing but sadly did not live to see this book completed

PREFACE

THE RIGHT HONOURABLE LORD TEBBIT C.H.

More than one book has been written about the Gloster Meteor and rightly so, since it was the first jet-engined aircraft to enter RAF service and the only one to see action on the Allied side during the Second World War. However, in Meteor Boys Steve Bond looks at the men (and it seems that there were no women) who flew the Meteor. In doing so Bond reminds us of a century in which the value put on human life in war or the preparation for war was very different from that of today, in Western circles at least.

The First World War had cost the lives of nine million combatants and seven million civilians, a rate of about four million a year. At Verdun and on The Somme over 600,000 men died in a matter of weeks. Thirty years later the nuclear weapons used against Hiroshima and Nagasaki cost around a quarter of a million mainly civilian lives, bringing to a close a conflict which had taken the lives of something between 50 and 85 million people worldwide again the majority of whom were civilians. Those two Great Wars of the first half of the twentieth century had between them claimed between 65 and 100 million lives, mostly civilians. In London we had experienced the Blitz in 1940 which killed 40,000 during a time when many of my generation did our homework in air raid shelters and became accustomed to walking to school past the un-cleared debris of the previous nights bombing. Within two or three years the tide of war had turned and the skies of London and the East of England were darkened as the overwhelming might of Bomber Command and the US 8th Army Air Force headed out to all but obliterate several great German cities initially taking terrible casualties themselves as they did so. It is all but impossible to estimate the number of casualties during the Cold War, which closed the twentieth century, but they were simply accepted as part of the price of peace. However, perhaps under the remorseless growth in the capacity of the media to bring the horrors of war into our living rooms, it has now become de rigueur for the prime minister to extend his condolences in the House of Commons to the families of any British serviceman lost in action. Indeed we have begun to mark the deaths of those murdered by the Isil terrorists with a minutes silence in the Palace of Westminster, a tribute not given to those murdered earlier by their IRA/Sinn Fein terrorist predecessors.

Such things were not thought of in the times related by Steve Bond. The Meteor Boys, of whom I am proud to be one, flew from the last months of World War Two, through some of the hot spots of the Cold War, notably Korea and indeed there are still just a few of us left flying the last few surviving Meteors today. We were a very mixed bunch, from Cranwell graduates, short-service commissioned and non-commissioned officers, regulars and auxiliaries, day fighter, night fighter, ground attack and reconnaissance pilots and navigators.

It took a lot of us to fly the total of 3,922 Meteors ever built. Now there are only five still flying and a few more living on in museums or as gate guardians. There were times when the Meteor had a slightly dodgy reputation because of the number which were being written off, often with their pilots, but readers of this book may well reach the conclusion that although the aircraft had weaknesses, such as its very high fuel consumption, many of the losses were down to the aircraft being operated in weather conditions in which its late 1930s-style instrumentation and lack of navigation systems were a frequent cause of losses. Another factor which these tales bring out, was the fall in the standards of training brought about largely by the sudden increase in the annual output of pilots from 300 to 3,000 a year as the Attlee government responded to the threat of soviet Russia and the Warsaw Pact forces from 1950.

Now, like the Meteor itself, we Meteor Boys (many of whom were part of that re-armament programme) are gradually fading away too, but some of us still meet up in the bar, toasting absent friends and sharing our memories of days together, some boring, some exciting, some tragic but many funny too. Steve Bond spent many hours listening to our ramblings and bringing them back to life. They all make great reading but let me confide that although there are some which left me very subdued, far more brought smiles to my lips and not a few which earned the writers greatest accolade, of outright laughter.

I particularly enjoyed reading the piece by Alan Colman () tells of being one of a course of 13 students at Driffield AFS in 1952 of whom five were failed and three killed which, even for those days, was somewhat below par.

Of so many remarkable stories I have no doubt that my favourite is that of Peter Greensmith () who was on a Meteor squadron in Egypt in 1953. During a simulated dogfight with a Venom he performed an unorthodox manoeuvre and lost the tail section of his aircraft. The Venom pilot did not see him bale out and he was posted missing, presumed dead. In fact he landed safely but in the middle of the Sinai Desert. It would be a shame to reveal the end of this adventure, but that alone is worth more than the price of this extraordinary compendium of the lives of the Meteor Boys.

INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

As with any aeroplane it is the aircrew and ground crew who are the people best placed to tell the story of the Gloster Meteors remarkable career and a good many of them have stepped forward here to recount their experiences. Many are exciting, some are sad, quite a few are humorous, but they are all typified by a great underlying affection for the type.

The Meteor has a secure place in history as not only the Royal Air Forces first operational jet-powered aeroplane, but the first such to serve with any of the Allied powers during the Second World War, its rival the de Havilland Vampire not joining a squadron until 1946. The first Meteors reached 616 Squadron (Sqn) in July 1944 and on 4 August the first success against a V1 flying bomb was achieved by Fg Off Dixie Dean. WO Sid Woodacre, a fellow pilot on 616 Sqn, described his own victory thus:

I was among the first to shoot down a V1 flying bomb. This was on 17 August 1944, when I was on an anti-Diver patrol under Biggin Hill control. I saw a V1 coming in south of Dover and caught up with it about three miles south of Canterbury. A Mustang was already sitting behind it but for some reason he didnt open fire. I was flying at about 400 mph and had no difficulty in overtaking both the Mustang and the V1 and then attacked and fired three short bursts at a range of about 200 yards. I saw strikes on its starboard wing and it then rolled over and went straight down. I saw it blow up when it hit the ground south of Faversham and explode harmlessly in fields below me, but the blast was enough to throw my Meteor about, even at 1,500 feet. If you were unlucky enough to hit the bomb itself, it would blow up and you could be in considerable danger.

Next page