All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner.

DEDICATION

To my dear father Cyril Norman Bond who introduced me to the wonderful world of aviation.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

GROUP CAPTAIN J K PALMER OBE FIMGT RAF (RETD)

Sixty years on, when apart and asunder, parted are those who are singing today. When you look back and forgetfully wonder, what you were like in your words and your play.

I was recently invited to talk to a mixed Rotary audience in that lovely hazy after-dinner hour, about life as a professional aviator in the post-World War 2 era. Aware that Id be facing some pretty switched-on, potentially critical folk, many with their own stories of life at university as budding surgeons, High Court judges and business barons, plus one ex-Tiller Girl, I planned my speech observing the Chatham House Rule and spent weeks titivating the English and trying to ensure that the form in which I would deliver my recollections would capture the splendour and elegance of the occasion.

On that memorable night I gulped down a precautionary brandy and courage as the president rose to introduce me, and looked out on the candlelit sophistication of dinner jackets and glamorous dresses to deliver my practiced blurb on The way we were. But even as I framed the words to grab their attention and get them on my frequency, an inner voice told me to tell it as it was, and not as perhaps they wanted or expected to hear. Flamboyantly, I discarded my script, beamed a smile to all corners of the room and started with, I actually joined the RAF by mistake.

As all octogenarians will know, the passing years play tricks on ones memory some of our greatest stories are about things that never happened at all! But I was keen not to perpetuate the post-war film-makers image of RAF types as handsome moustached carefree chaps with one eye on a pretty girl and the other on Rita Hayworth, or the kick the tyres, light the fires, gung-ho arrogance of the little creep played by Tom Cruise in Top Gun. The boys and men in uniform that I worked or flew with post 1945 were a microcosm of British manhood, ranging from lads who just scraped through the 11-plus exam to university graduates, coming from poor as a church mouse families, to the rich and titled.

Whatever the secret was in the Aircrew Selection and Training corridors, the mix of pilots and navigators/system operators arriving in fighter squadron crewrooms in the 1950s and 1960s were seamlessly glued by tradition, and as George Black wrote in Steve Bonds book Meteor Boys, There was great camaraderie, but if you didnt show a bit of spark and let yourself go occasionally, you werent part of the fighter force. I hasten to add that the bomber/strike, maritime Kipper fleet, and transport fraternities all had similar bonds and allegiances, but as a fighter boy you walked tall and carried your head high.

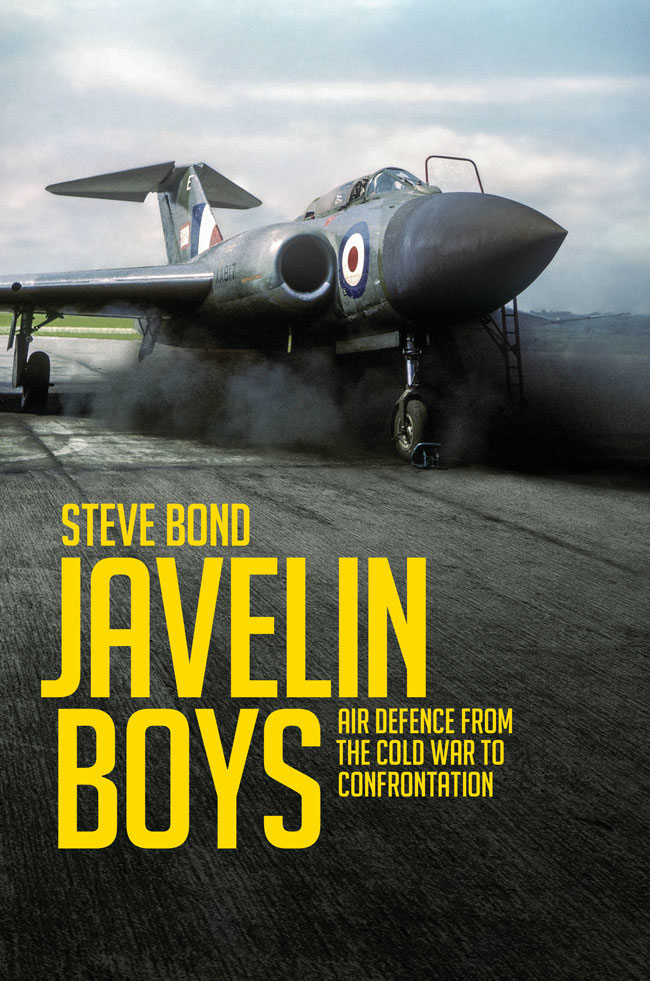

Looking back to when the Javelin entered service some 60 years ago, it is worthwhile reflecting on how life was then for the lucky chaps who flew the new aircraft. The massive 1950s build-up of aircraft and crews to fight a conventional war, had seen the jet largely replace piston-engined aeroplanes. Many pilots serving on 8/12 year commissions had been lured to civil airlines. Many permanent overseas bases became staging posts, or were supplemented in times of tension by fighters of the new Tactical 38 Group, in-flight refuelled from the UK. At a time when missile technology, both air and ground launched, was really taking off, some poor souls even fell for the line that their best career path was to sit in a tent and press pretty buttons!

But no such cynicism blurred my vision back then, or spoilt the thousand hours I spent in the Javelin, wearing the famous colours of 23 Squadron at Coltishall and Leuchars, before the Red Eagles converted to the Shiny silver pursuit ship the Lightning Mk.3 in 1965. To be truthful, my colleagues and I knew little about the worlds politics or cared much! We were part of a proud, vibrant, dynamic force that faced a deadly serious enemy that confronted them from the Arctic Circle down to the Mediterranean.

RAF stations in the UK, and a great many overseas in Germany, the Med, Middle and Far East, were exciting places both in terms of the flying and the family life, with the vast majority of wives living on base, and the various messes the centres for a great social life. In the fighter world you might live anywhere from Lossiemouth in Scotland, down to the south coast of England, or overseas accompanied by families on any one of those many far-away bases, most with guaranteed sunshine, cheap cars and alcohol and a way of life that was so different from that in the UK. In 2017, the world has shrunk, and places like Hong Kong, Singapore, Calcutta, Bahrain, Aden and Cairo, with magic in their names and a unique appeal in lifestyle, culture, customs, dress and food, have lost their mystery and charm by becoming westernised. By 1962, fighter crews having spent most of their flying up and down in an hour, were routinely flying long-range single legs and full squadron detachments using in-flight refuelling.

Any aviator will tell you that being a part of this or that squadron, flying this or that aircraft, from this or that base, was the happiest most fulfilling period in their lives. In my 38 years I think that the 50s and 60s were the best for the thrilling mix of flying, social life and the promise that there was more to come as new aircraft, with undreamt of performance and reliability, entered service. On reflection, I can honestly say that I enjoyed flying whatever was put before me, even though when I returned from a US exchange tour, having flown the F-101 Voodoo and the early US Marines version of the F-4 Phantom, the Javelin was a bit of a let-down in performance and electronics capability. Like almost all British combat aircraft, the Javelin was too long in development and didnt reach anything like its full potential until the Mk.9 entered service. But and as the RAF always did in my era both engineers and aircrew got the very best out of what British industry was able to provide, and I remember 23 Squadron as a very happy outfit, immensely proud of its majestic beast.

Later in my career, when serving in MoD Operational Requirements and the defence industry, I was to realise and even understand why the RAF seldom if ever, got the performance and reliability that it had clearly specified and negotiated for. Planned in-service dates were seldom met, and stipulated minimum acceptable performance levels seldom achieved. Partly, that was because industry (both UK and US) had a knack in their extremely competitive world, of promising what they knew could never be achieved and, partly because the procurement agencies were not professionally acute, with most linked to politicians totally uninterested in the armed services.