History with its flickering lamp stumbles along the trail of the past, trying to reconstruct its scenes, to revive its echoes, and kindle with pale gleams the passion of former days.

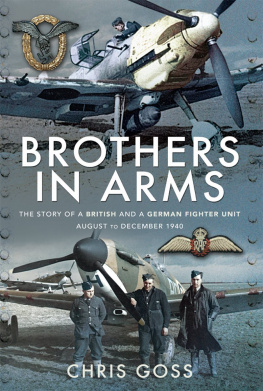

The history of air warfare is well documented because every take-off, every landing and every engagement of the enemy was logged and recorded. That record of action is generally accurate and comprehensive but statistics alone do not tell the full story. To complete the picture, eye-witness accounts are invaluable as they bring the story to life by illustrating the tension, the emotions and the atmosphere surrounding the events.

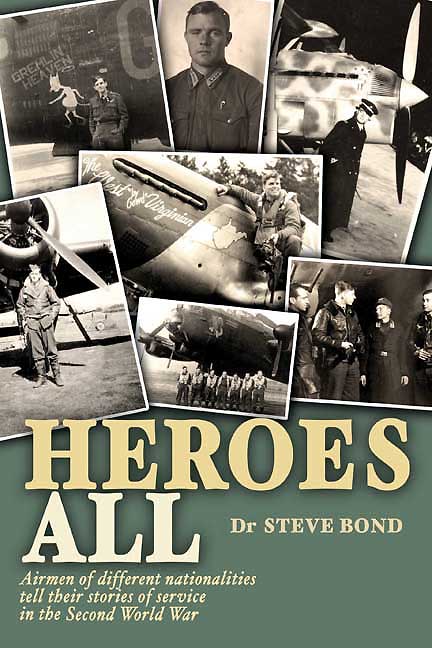

Steve Bond has done a remarkable job in gathering the tales of over 100 people from the armies, navies and air forces of six nations, both aircrew and ground crew, plus civilians such as Alex Henshaw. He has sensibly avoided the temptation to edit their contributions, thus preserving the very personal nature of their accounts which reveal their characters and the differing approaches of the various nations.

The result is a compelling and fascinating compilation of stories from every area of air warfare which add so much to the bare statistics. This is a first class book which will be a most useful reference for anyone with an interest in the history of air warfare.

INTRODUCTION & ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

HEROES

Hero: A man distinguished by extraordinary valour and martial achievements; one who does brave or noble deeds; an illustrious warrior.

Oxford English Dictionary

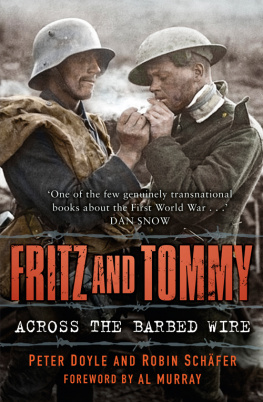

In the world of the 21st century it has become commonplace to refer to high achievers in almost every walk of modern life as heroes. One only has to turn to the sports pages of our daily newspapers to find the term applied to, for example, footballers who have saved their national team from disgracing itself against the opposition. Worthy though such endeavours may well be, turn back the clock sixty years or more, and the common meaning of the term was very different and indeed little used.

Then, young men and women of a similar tender age to todays sporting stars were fighting a very different kind of campaign, with far more serious, almost unimaginable, potential consequences for both themselves and their losing side. A 2007 study of the United Kingdom premier football league revealed that the average age of the team players at that time was a little over twenty-six years . The average age of crewmen in Royal Air Force (RAF) Bomber Command during the Second World War was just twenty-two. An airman in his mid to late twenties was often referred to by his comrades as the old man, while at the other extreme, the youngest airman to lose his life during the Battle of Britain, air gunner AC2 Norman Jacobson, was just eighteen when he died during the late evening of his very first day of operations on Blenheim-equipped 29 Squadron. His body was recovered a day later and buried at sea, and he is commemorated on the Runnymede Memorial. Today such fresh-faced youngsters, hardly out of school, are again making the supreme sacrifice in conflicts in far-flung places like Afghanistan.

The toll in human lives throughout the Second World War was enormous. In Bomber Command alone, 55,573 airmen lost their lives in action, out of a total of 70,253 casualties for the entire RAF. Similarly, Luftwaffe losses, which will probably never be known for certain, amounted to 96,917 up to the end of 1944, after which no reliable records remain, even if they were completed. United States Air Force (USAF) records indicate 79,265 killed in action in just the European theatre of operations (ETO).

Looking back, the first wartime heroes I came across were during my school days in the 1960s. At that time, only a decade and a half after the end of the war, there was not the intense interest in that conflict that is so prevalent today, so those who had been there perhaps tended not to be paid much attention. At my school, the master who was the officer in charge of the RAF section of our combined cadet force, one N H Blanco (inevitably) White had been, so I later found out, a pilot during the war, while my English master, John Perfect, a very quiet and unassuming man, had been one of those incredibly brave souls in the Glider Pilot Regiment who had flown Horsas into Arnhem. Again, this fact was not widely known, I recall being told about it by another boy one day, and was only able to confirm it recently. Sadly, in the intervening years, John Perfect had died; how I would have loved to have talked to him about his role in that momentous event.

In recent years there have been many books published that have included the thoughts and memories of those who were there. Hearing the airmen bring to life such well-known events as the Battle of Britain, the bomber war, the air war on the Eastern Front, as well as lesser-known aspects, is a privilege not granted to many today. This is not just because the veterans are reluctant to talk about their experiences; often I have found that they need to be persuaded that the listener is genuinely interested they worry about boring us! Today, the survivors of the armed forces that took part in that great conflict are all elderly and they are rapidly fading away. Yet still they retain almost to a man, a remarkable degree of self-effacement, and during my many visits to interview them, the conversation frequently starts with something along the lines of: Oh, I didnt do very much. As former Warrant Officer Jack Bromfield of 158 Squadron put it:

The memories are still there; theyre there all the time. You can go maybe two weeks and think nothing; theres a little snippet in the paper or on the television and suddenly it all starts to wind up again. Or somebody mentions a name, youve forgotten about him for years, and suddenly you remember about him.

Occasionally too, a subliminal feeling of guilt can be detected; not, by any means, guilt at what they were called upon to do, but guilt that they had survived when their comrades did not. There is rarely any political aside to their stories and for me, this attitude is best summed up by something written by the renowned Luftwaffe night-fighter ace Major Heinrich Prinz zu Sayn-Wittgenstein, who scored eighty-three victories against allied bombers, but failed to survive the war. The following passage appears in his biography Laurels for Prinz Wittgenstein written by fellow officer Werner Roell :