Dedication

DEDICATION

To all of the wounded veterans, as well as active-duty soldiers, for their heroism and sacrifice, and to the canine heroes and their trainers who have helped change, improve, and save our veterans lives.

Chapter 3: Guide Dogs

GUIDE DOGS

According to an article titled The Seeing Eye, written by The Seeing Eye co-founder Dorothy Harrison Eustis and published in the November 5, 1927, Saturday Evening Post, the cost of training a guide dog at that time was about $60, which included the initial cost of the dog. Today, with an average price tag of $50,000 (some experts suggest as high as $70,000) to breed, raise, and train one guide dog, these canines undergo a comprehensive training program that only the best of the best complete.

Guide dogs, once referred to as blind guides, can be traced to the first century AD and the buried ruins of the ancient Roman town Herculaneum, according to the article History of Guide Dogs on the International Guide Dog Federations website (www.igdf.org.uk). An article titled The History of Guide Dogs in Britain from the Guide Dogs (UK) website (www.guidedogs.org.uk) tells of early examples of European art that depict the blind accompanied by dogs. Stories are told of an eighteenth-century Parisian hospital for the blind that attempted to train guide dogs, while a blind sieve-maker in Vienna was said to have trained a dog so effectively for his own use that people thought he was sighted.

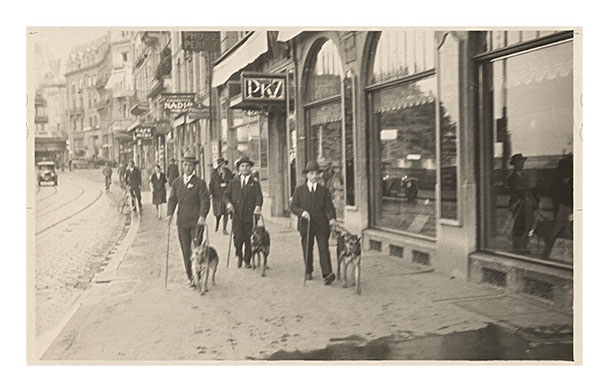

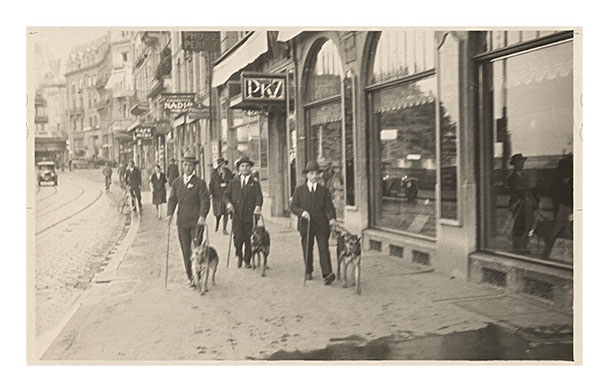

Training on the streets of Lausanne, Switzerland, with German Shepherd guide-dog candidates.

Military dogs deployed by the French Legion during World War I who were unable to fulfill their combat duties for various reasons, including injury, were retrained to be the companions of blind ex-soldiers. Despite the accessibility of dogs, however, it was not a very popular service because, according to Ernest Harold Baynes, author of Animal Heroes of the Great War (1925), of the feeling that a blind man led by a dog must necessarily appear to be an object of charity.

The modern guide dog story really begins during World War I when the Germansalways way ahead of the game when it came to breeding, raising, and training dogsassigned German Shepherd Dogs to soldiers who had been blinded by mustard gas. The aforementioned article History of Guide Dogs tells us that German physician Dr. Gerhard Stalling was walking the grounds of a veterans hospital with a blind patient. Called away suddenly, Dr. Stalling left his German Shepherd Dog with the patient to keep him company. Upon returning, he believed that the dog had been looking after the patient, trying to help him. Thereafter, Stalling began exploring ways of training dogs to become guides, and, in 1916, he opened a guide-dog school in Oldenburg. The facility shut down within a decade, but by then a large guide-dog school in Potsdam, near Berlin, had opened. The school was capable of accommodating around 100 dogs at a time and providing up to twelve fully trained guide dogs per month. In its first eighteen years, the article states, the school trained over 2,500 dogs with a rejection rate of just 6 percent.

The guide-dog school came to the attention of Dorothy Harrison Eustis, a wealthy American dog breeder living in Switzerland who, at the time, was interested in the scientific breeding of German Shepherd Dogs for the desirable characteristics of alertness, responsibility, and stamina. Eustis, a breeder and trainer of German Shepherds for the army, police, and Red Cross, saw firsthand how the Germans were rehabilitating their war blind and was impressed by what she witnessed at the school. It forever changed her way of thinking about the future of blind people. She began to think more broadly, wondering if selective breeding could develop guide-dog qualities more widely. If so, why not selectively breed and train dogs to assist the blind?

Eustiss previously mentioned Saturday Evening Post article changed the lives of the blind everywhere. She wrote:

In darkness and uncertainty he must start again, wholly dependent on outside help for every move. His other senses may rally to his aid, but they cannot replace his sight. To mans never failing friend has accord this special privilege. Gentlemen, I give you the German shepherd dog

No longer dependent on a member of the family, a friend, or a paid attendant, the blind can once more take up their normal lives as nearly possible where they left them off

That crowds and traffic have no longer any terrors for him and that his evenings can be spent among friends without responsibility or burden to them.

The article caught the attention of Mr. Frank of Nashville, Tennessee, who read it to his nineteen-year-old blind son, Morris. The young man had lost his sight in one eye in 1914 during a riding accident when he was six years old. Ten years later, his other eye was damaged beyond repair in a high school boxing match.

Morris Frank with Buddy, who would later become a national heroine.

Morris Frank wrote to Mrs. Eustis, asking her to train a dog to help him. In April 1928, he set sail for Europe, accepting Eustiss invitation to visit her school and see about a guide dog for himself. Before guide dogs, people who were blind were simply marginalized. Few, if any, provisions for them existed. Such was the case with Morris Frank, who, because he could not fend for himself on his travels overseas, was deemed a package rather than a passenger. The crew went so far as to restrict his movement, and he was not permitted to leave his room to move about the ship without someone from the ships staff accompanying him, writes Kate Kelly in The First Seeing Eye Dog Is Used in America in 1928 on her America Comes Alive! website ( www.americacomesalive.com ).

Not far from Eustiss Fortunate Fields kennel in the Swiss Alps, Frank was paired with a German Shepherd Dog named Kiss, although he quickly changed the dogs name to Buddy because, as the story goes, he could not imagine calling out, Come, Kiss!

Within weeks, Frank, with Buddy in harness, was smoothly and confidently navigating the streets of Vevey, Switzerland. Returning home, Frank and Buddy disembarked in New York City, where they were greeted dockside by a crowd of spectators, reporters, and photographers. On a dare from one of the reporters, Frank instructed Buddy to cross West Street, a particularly treacherous waterfront highway filled with cabbies, trucks, and drivers hollering out their windows. Frank worried that he was expecting Buddy to handle more chaos than he had faced in training.

Frank trusted Buddy to lead him across crowded, busy city streets.

As Frank stepped from the curb, he put his life in his dogs training. He surrendered all control to Buddy, and, for three long minutes, Frank was completely directionless. Upon reaching the other side, he wrapped his arms around Buddy and praised her: Good, good girl! She had done her job. As a trained guide dog, she had become Franks eyes, able to safely guide him across a hectic intersection.

Next page