Copyright 1998 Lionel Leventhal Limited

First Skyhorse Publishing Edition 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Rain Saukas

Cover image from US National Archives

Print ISBN: 978-1-5107-0358-2

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-0367-4

Printed in the United States of America

Contents

List of Illustrations, Maps and Diagrams

Maps and Diagrams page

Introduction

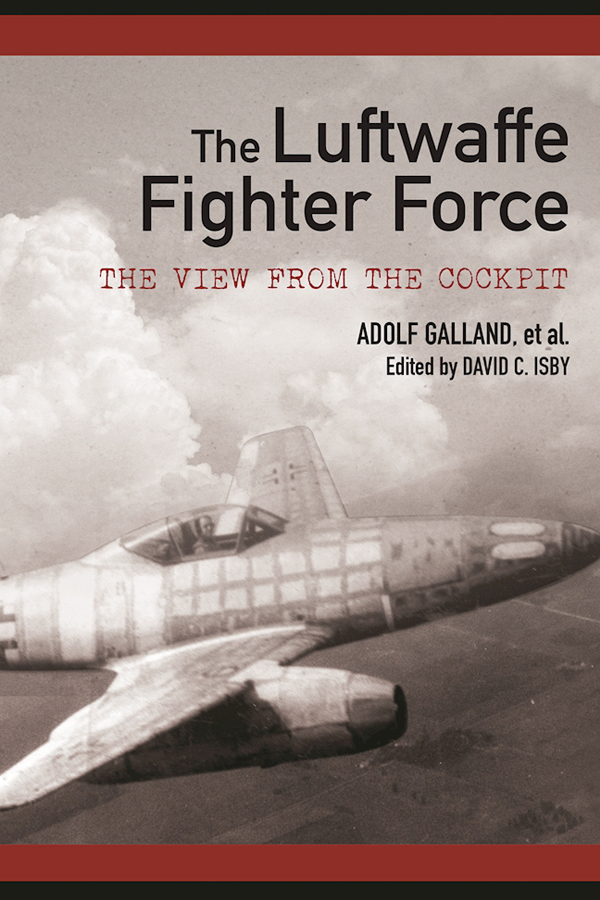

This book is a collection of German fighter leaders views of different elements of their part in the Second World War. The authors all led from the cockpit, often with great success, as is shown by their score of air-to-air victories (indeed, with its multiple authors, this book has the highest victory total of any book on air combat). They were the men who determined usually through improvisation rather than efficient German staff work how the Luftwaffe fighter force was to do battle throughout the Second World War. These accounts are written by professionals, for other professionals.

But the accounts here are not those familiar from memoirs of air combat. The reader will not find accounts of contrails in the central blue, the cries of horrido! and pauke, pauke over the radio, or even the dilemma of whether to fall in a doomed cause or abandon the struggle and ones comrades. Rather, they recount the history of the Luftwaffe fighter forces aircraft, operations, tactics, training, technology, and aircrew.

These documents represent the command debrief of many of the Luftwaffes fighter leaders, being done weeks or months rather than years after the flying and fighting had stopped. It was good that these debriefs were done while memories were fresh, for the prisoners were without official documents except, in some cases, their flight logbooks. This also explains why there is less emphasis on the successes of the opening years of the war now faded in memory and more written about the last years of the Defense of the Reich. It was also the area in which the USAAF was most interested.

The authors compiled most of these documents as prisoners of war, under the authority of the US Army Air Forces, while being held in Germany and England. The Air Prisoner of War Interrogation Unit (APWIU), under Major Max von Rossum-Daum USAAF, started the procedure in occupied Germany, at Heidelberg. The bulk of the work was carried out after the prisoners had been flown to England, at the Combined Services Detailed Interrogation Centre, Camp 7, at Latimer, Buckinghamshire, and another interrogation center at the nearby village of Beaconsfield. The prisoners were, later in 1945, flown back to Germany and the debriefs continued at Kaufberen, Bavaria, for two months before many of the prisoners some had been released returned to Latimer, where the process was completed by the end of 1945. After that, some of the prisoners started to work on historical narratives requested by the USAAF.

Overhanging the interrogation process was the shadow of the war crimes trials. Indeed, one of the minor contributors to this volume, Generalfeldmarshall Erhard Milch, the Luftwaffes Director General of Equipment in 194144, was tried and sentenced to 15 years for his involvement with slave labor. The other authors were also under investigation, though they were all eventually cleared. However, the subject matter of these interrogations, which focused on the air war itself rather than involvement with issues that led to prosecution with the notable exception of some dealing with in-unit discipline is unlikely to have affected interrogations on other issues.

The accounts cover the full range of German fighter operations. They are, quite literally, the first draft of the history of the Luftwaffe fighter force, and make up in immediacy what they may lack in reflection and opportunities for archival research. They include areas often overlooked in history books, such as the air-ground fighter operations and cooperation with the navy. Each of the subjects was interrogated mainly about topics on which they had direct personal knowledge. The intense internal secrecy of the German war effort made claims to knowledge that did not come from such hands-on experience suspect.

These accounts are earlier and less refined than the better known series of historical studies written by former Luftwaffe officers some volumes of which have been reprinted by publishers such as Greenhill Press and Garland collectively referred to as the Karlsruhe studies. The accounts in this volume are similar those incorporated in the Karlsruhe studies. Many of the authors of this volume, including Galland, went on to work on them. However, when they were under interrogation they were unable to make use of Luftwaffe documents and records, the vast majority of them had by design and fortunes of war alike been destroyed. There was, and remains, much less original documentation for the history of the Luftwaffe than for the other German services.

These later studies corrected many of the inevitable errors and omissions that were recorded in the initial interrogations. What the Karlsruhe studies did incorporate and what these debriefs largely omit are the Luftwaffe authors political biases, sharpened over the years as the shock of defeat grew less and the time for discussions among them increased. The fact that the authors were, unlike in these interrogations, no longer in uniform and were working for German intermediaries rather than directly for USAAF interrogators may also have had an impact. For example, the Karlsruhe studies tended to suggest that Germany lost interest in strategic bombing after the death of General Wever in the 1930s. This suited some of the Luftwaffe authors, for it allowed them to pose as morally superior to the victorious USAAF and RAF: they would never have made war on a civilian population the way they did.

This view also suited the USAF sponsors of the studies, for a different reason. They could show that the Luftwaffe failed because it rejected what the USAF then saw as the true light of airpower strategic bombing and was instead left under the control of ground officers and led into the delusions of emphasizing combined arms cooperation with the army, becoming a mere tactical air arm which doomed it to defeat. With the Luftwaffes documents destroyed, no one could then contradict either view.

We now know from the more recent works of historians such as Williamson Murray, R. J. Overy and Richard Muller, among others that the Karlsruhe studies, while remaining valuable sources, present a slanted view of the Luftwaffes actual operations and thinking. In these documents, it appears unlikely that any of the contributors are much concerned with the use to which their information will be put by the Americans, as so long as it was not for prosecuting them for war crimes. None of these fighter leaders lament the absence of a strategic bombing emphasis. Rather, they complain of too much of an emphasis in this area for too long. Complaints about non-flying generals in the chain of command are also conspicuous by their absence Galland is respectful of the efforts of contributor Beppo Schmid as a commander of fighter units, even if not as an intelligence officer though such a thing has been anathema to the USAAF and its successors.