Published by

Grub Street

4 Rainham Close

London

SW11 6SS

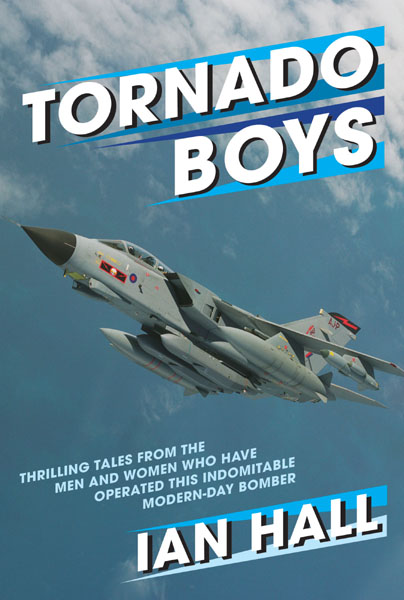

Copyright Grub Street 2016

Copyright text Ian Hall 2016

A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library

ISBN-13: 9-781-910690-13-0

eISBN: 9-781-910690-76-5

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner.

Printed and bound by Finidr, Czech Republic

CONTENTS

Ian Hall |

Dick Bogg |

Vic Bussereau |

Mike Crook |

Pat King |

Jerry Witts |

Wally Grout |

Steve Randles |

Alan Threadgould |

Les Hendry and Peter Gipson |

John Peters |

Simon Dobb |

Gordon Niven |

Ian Hall |

Paddy Teakle |

Gordon Robertson |

Iain McNicoll |

David Robertson |

Rob McCarthy |

Sasha Sheard |

Ian Hall |

INTRODUCTION

Ian Hall

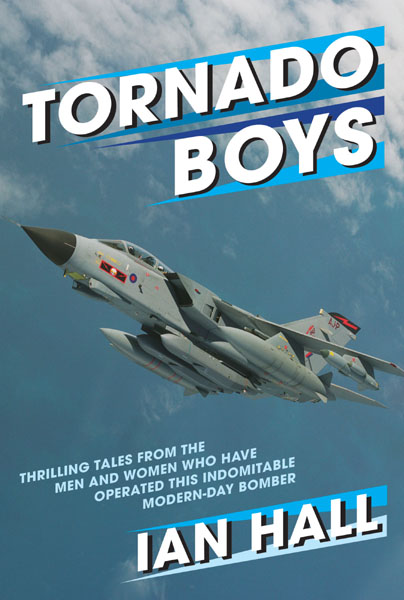

The Tornado GR1 was conceived as a tactical nuclear bomber, a low-level interdictor for the Cold War era. Its crews knew their job, which was to demonstrate the expertise, equipment and readiness required to deter the Warsaw Pact from attacking NATO nations. But when it had been in service for little over a quarter of its life a series of extraordinary transformations began. The Tornado force participated in live combat far from the anticipated theatre of operations. The Warsaw Pact collapsed. The aircraft was upgraded to GR4 standard, outwardly almost indistinguishable but with combat capability undreamt of in the early days. Tornados would continue, for many years, on operations as different as chalk from cheese from those for which the aircraft had been designed.

This volume, a compendium of tales by those who have flown, serviced, supported and commanded Tornado operations, gives a flavour of the many and varied aspects of the Tornado GR1/GR4 world over the years. Most of the contributors are people I met during my own, single Tornado tour, and many of them went on to experience the extraordinarily diverse nature of the aircrafts eventual tasking.

CHAPTER 1

TO BE, OR NOT TO BE

Mother Rileys Cardboard Aeroplane and Must Refurbish Canberra Again were phrases commonly coined to represent MRCA. There seemed to be more than a degree of scepticism around the RAF as the Tornado was prepared for service entry. This was to some extent understandable. Vulcan people would not have regarded it a worthy successor to their mighty jet; not least, it possessed only a fraction of the range and payload. Buccaneer crews were very much attached to their steeds, and fiercely loyal to the ethos of the fleet. And yet the Tornado was to replace both types.

And even when, by the late 1970s, the Tornado was approaching service acceptance, RAF people could have been forgiven if they werent rushing to place bets on its entry into service. After all, many of them had grown weary of seeing exciting projects being derailed by changes of the political mind. TSR2 cancelled as its test phase was about to accelerate; F-111 the order cancelled before the first airframe had been delivered; P1154, the supersonic Harrier cancelled before metal had been cut; likewise with the Anglo-French Variable Geometry machine (AFVG). The last had foundered partly due to difficulties in reconciling the plans of two different nations. Even though the international concept had subsequently been proven with the successful delivery of the Jaguar, Puma and Gazelle, there still remained a suspicion that the Anglo-German-Italian Tornado could yet founder.

Amidst the doubt, though, there were those who remained optimistic. Members of the international project staffs and testing teams were already seeing at first hand the immense potential of the new aircraft, and were determined to bring it to fruition. Among them was Dick Bogg, a friend of many years standing who, through a later series of command postings, became a stalwart of the Tornado world.

________________________________

AIR COMMODORE DICK BOGG (RETD)

In the summer of 1971 I was at Boscombe Down working as a trials officer flying the navigation and weapon aiming system trials on the Phantom FGR2. One Wednesday afternoon, as I climbed out of the Phantom, I was asked to report to my wing commander who announced calmly, Tomorrow, you are to attend an interview in London for a job with the MRCA. There was not a deal of choice in the matter, but I had to ask him, Whats MRCA? He explained that I was on the short list for an avionics test appointment in the flight-test department of the international project office in Munich for the new, secret Multi-Role Combat Aircraft, still on the drawing board but having recently entered the development phase. In the space of five minutes I learned that it was being progressed jointly by West Germany, Italy and the United Kingdom (Belgium, Canada and the Netherlands having already pulled out) as a single replacement for ageing F-104 Starfighters, Vulcans, Canberras and Buccaneers. The new aircraft would have all manner of state-of-the-art sophistication and was already being nicknamed the all-electric jet. It was Europes biggest ever military project and was set to topple American dominance in the field; thus the political and industrial stakes were high.

Next afternoon I reported to the MoD in Whitehall for my interview with the head of the programmes systems engineering division. There were two other candidates, one civilian, one military. It was unusual for an RAF flight lieutenant to undergo such a job interview and I found it somewhat daunting. There was a general chat, followed by probing questions on navigation and weapon aiming system testing, statistics and suchlike. It made for an interesting forty-five minutes, following which I was asked to report straight back to work.

I arrived back at Boscombe at 5.30pm, whereupon my boss immediately told me that Id got the job; I was to start work in Munich on Monday! I was to leave the RAF on loan to NATO, essentially becoming a civilian on contract. All very odd. Also, I couldnt believe that a selection had been made, approved by the MoD and agreed by the RAFs personnel department all in the space of two hours. Although I managed to negotiate a short delay, it was still a whirlwind departure from the RAF, and I soon found myself living in a Munich hotel. The day I arrived was the start of Oktoberfest timing impeccable!

I was to work for the NATO MRCA Development and Production Management Agency (NAMMA), and in the city the next morning I began my first ever day of work in civilian clothes. My new boss was a German civil servant flight test engineer. There was also another German in the flight-test section and we would be getting a young Italian air force captain in due course. I renewed acquaintanceship with my earlier interviewer, Mr Wason Turner, and was taken to meet the GM and his deputy. The former was a Luftwaffe two-star general while the latter was an RAF air commodore, both also on loan.

NAMMA shared an office block with Radio Free Europe, the broadcaster to east European countries; there were many stony-faced characters in the vicinity, and it seemed incongruous, at the height of the Cold War, for the government agency supervising the most secret NATO programme of the period to be sharing a building with RFE. Security was important, but one day when the DGM was holding a meeting in his office the door burst open and in rushed a German major. He clicked his heels and shouted that there was a bomb scare the DGM would have to evacuate his office. With true British phlegm, the DGM looked over his half-moon glasses at his colleagues, responding with: I dont think we need to worry about a bomb, do you gentlemen? The meeting continued.

Next page