The

Lumberjacks

The Lumberjacks

Donald MacKay

Third Edition

NATURAL HERITAGE BOOKS

A MEMBER OF THE DUNDURN GROUP

TORONTO

Copyright 1978, 1986, 1998, 2007 by Donald MacKay

First edition (McGraw-Hill Ryerson): 1978

Paperback edition (McGraw-Hill Ryerson): 1986

Second edition (Natural Heritage Books): 1998 (Second printing: 2002)

Third edition: 2007

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanic, photocopying or otherwise (except for brief passages for purposes of review) without the prior permission of Dundurn Press. Permission to photocopy should be requested from Access Copyright.

Published by Natural Heritage Books

A Member of The Dundurn Group

3 Church Street, Suite 500

Toronto, Ontario, M5E 1M2, Canada

www.dundurn.com

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

MacKay, Donald, 1925

The lumberjacks / Donald MacKay. 3rd ed.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-55002-773-0

1. LoggingCanadaHistory. 2. LoggersCanadaBiography. I. Title.

SD538.3.C2M32 2007 634.980971 C2007-902130-1

1 2 3 4 5 11 10 09 08 07

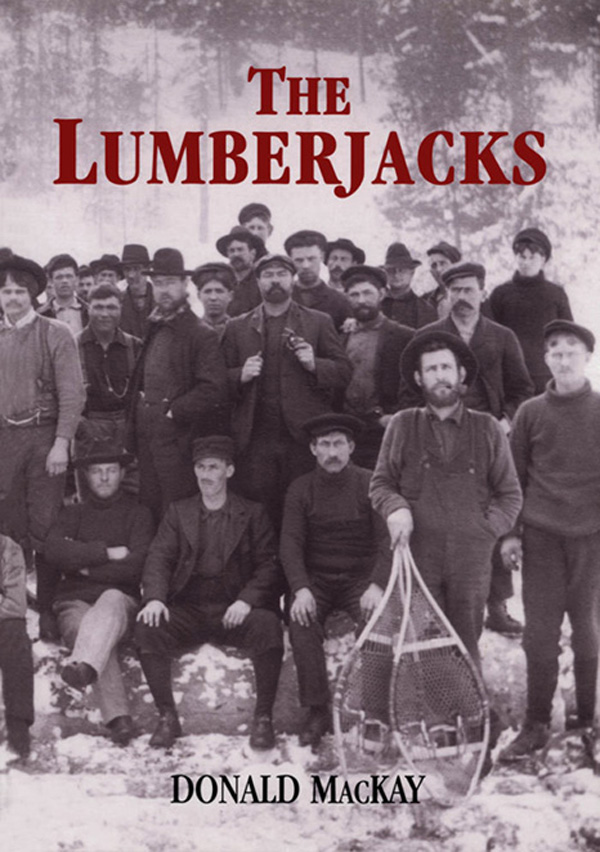

Cover photo courtesy Library and Archives Canada, PA 12605

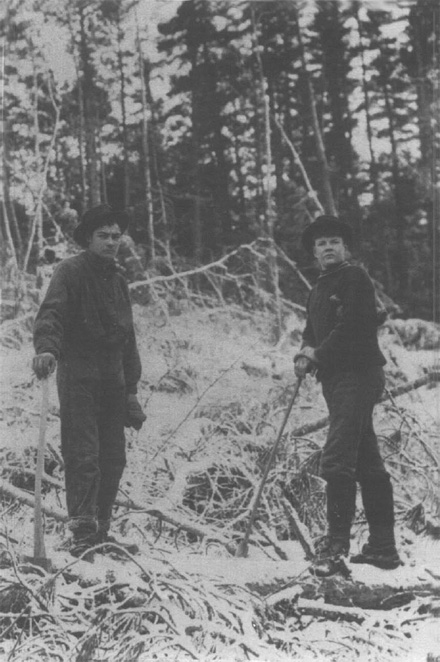

Frontispiece photo courtesy the publishers personal collection.

Cover design by Blanche Hamill, Norton Hamill Design

Printed and bound in Canada by Hignell Book Printing of Winnipeg

Care has been taken to trace the ownership of copyright material used in this book. The author and the publisher welcome any information enabling them to rectify any references or credits in subsequent editions.

J. Kirk Howard, President

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council for our publishing program. We also acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program and The Association for the Export of Canadian Books and the Government of Canada through the Ontario Book Publishers Tax Credit Program and the Ontario Media Development Corporation.

To my family: Barbara, Dorothy, Marina, Karen, with love

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

An interest on the part of several organizations and many individuals in preserving the oral history of the lumberjacks has made this book possible.

I would like to acknowledge the special assistance of the Abitibi Paper Company Ltd., Consolidated-Bathurst Limited, the James Maclaren Company Limited, The Price Company Limited, and the Reed Paper Group. For their interest and support, I am grateful to J. G. MacLeod and Donald Farrell of Montreal, Paul Masterson and K. D. Greaves of Toronto, and J. F. Maclaren of Buckingham, Quebec.

The Explorations Program of the Canada Council, Ottawa, provided a travel grant.

Many who contributed recollections and photographs are, by the nature of their contributions, mentioned in the narrative or in the source notes. There were many others who smoothed the way. I benefited from travelling the Ottawa Valley with Ewan Caldwell, whose roots go back to the square timber days, from exploring northwest Ontario with R. B. Loughlan of Toronto, and from the knowledge of A. D. Perley of Trois-Rivires and the Saguenay historian Monseigneur Victor Tremblay of Chicoutimi, Quebec. For their kindness in reading the manuscript I thank Herbert I. Winer, a Montreal-based director of the Forest History Society of Santa Cruz, California, and Terence Brennan of Montreal, whose contributions to the history of logging have been extensive.

Donald MacKay

INTRODUCTION

Along with red-coated Mounties and pictures of Niagara Falls, one of the abiding images of Canada around the world has been a shaggy, lonely figure swinging an axe amid the snow and evergreens of the north woods.

Fifty years ago the Ontario forestry journal Sylva published a somber memorial to that image: Soon the old-time lumberjack will be forgotten. He has had his day. The rising generation will not know him. Canada owes much to the old time lumberjack who was one of the most fearless pioneers of our land. May his memory never die.

That was written shortly after World War II. Nearly thirty years later, however, when I began travelling the country to research The Lumberjacks, I found scores of white-haired veterans ready and willing to recall, with vivid detail, their labours in the woods with hand and horse. Some had gone into the camps as teen-age boys before the turn of the century.

The 19th century had spawned a breed of hard-working lumbermen with pride in their skills and rough codes of conduct. They called themselves lumberers, shantymen, timber beasts, les bucheronand, more recently, lumberjacks in eastern Canada, loggers in British Columbia.

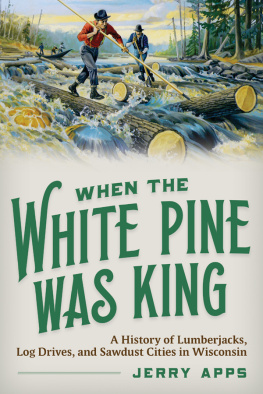

Of the three inter-woven ages of eastern Canadian logging, the first belonged to the bearded square timber men who hewed great baulks of white and red pine and drove them in huge rafts down the rivers to Quebec City, from where they were shipped to England in leaky sailing ships. Halfway through the 19th century the second agethe lumber industrybegan to supply sawn timber to the growing towns of the United States as well as Canada. Then in the early 1900s the pulp and paper industry brought huge amounts of American and British capital into Canada and opened seemingly endless forests of spruce and balsam fir.

In British Columbia, where logging, like settlement, came late, migrant woodsmen, some from as far east as the Maritimes, founded a new phase of the industry in the late 1800s. Within a generation they replaced oxen and horses with steam power to handle the giant Douglas firs and cedars of the rain coast.

Across the country, farm boys had gone to the woods, that being the only winter work. Town boys had gone for adventure or to escape their troubles. ImmigrantsSwedes and Finns more often than notresumed the trades they had learned so well in the forests of northern Europe. They broke the cold, hard monotony of camp life far from home with songs, tall tales and card games. There was surprisingly little drinking in the camps, but when their work was done and their pay in their pocket they went on sprees in town.

Small boys in lumber towns looked up to them, especially the white water men who drove logs down wild rivers to market. In the Ottawa Valley town of Renfrew youngsters used to play lumberjacks in preference to the cowboys and Indians kids played elsewhere.

Like cowboys or sailors they developed their own lingo, some of which carried over into urban usage. To get into a jam derived from log jams in a river drive. Skid row, some say, began as the west coast skid road on which logs were maneuvered into the water for transport to the mill. There are other words in common usage, such as Bull of the Woods, but who these days has heard of such common features of the lumber camps as the Crazy Wheel or the Go-devil or the Walking Boss?

Early lumbering, like farming, was a conservative business. Stoves had been used in town for a generation before they replaced the open fires in the center of lumber shanties. The crosscut saw, which permitted two men to produce twice the timber two axemen could cut, appeared in the camps long after it was introduced elsewhere.