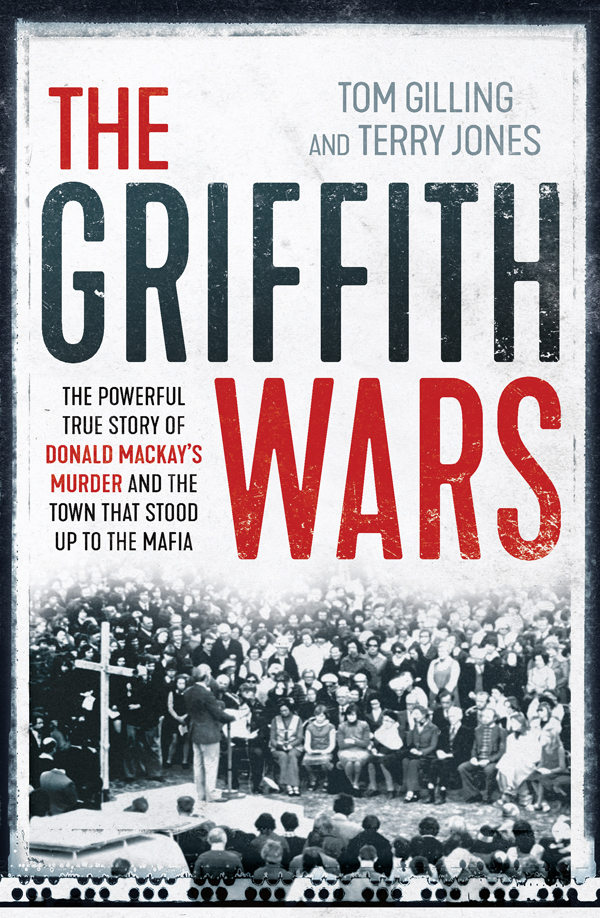

First published in 2017

Copyright Tom Gilling and Terry Jones 2017

All photographs reproduced courtesy of Terry Jones, former editor and photographer/journalist The Area News

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email:

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available from the National Library of Australia

www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 76029 591 2

eISBN 978 1 76063 944 0

Set by Midland Typesetters, Australia

Cover design: Luke Causby / Blue Cork

Front cover image courtesy of Fairfax Media

Contents

Domenico Trimboli was 33 years old when he and his wife, Saveria, bought Farm 869, near Griffith, in the heart of the Murrumbidgee Irrigation Area in far western New South Wales. They were among the thousands of poor Italian migrants who began arriving in Australia in the 1920s.

In the early days, living conditions were primitive, with homes made from hessian bags whitewashed inside and out (they gave the settlement its name, Bagtown) and bare earth floors. Many of the early soldier-settlers walked away broken-hearted, unable to eke an existence from their tiny plots of land, but their places were soon taken by migrants eager to create a new life for themselves in their adopted country. Crops grew in the rust-coloured soil without natural rainfall, watered by the mighty Murrumbidgee River. To those like Domenico and Saveria Trimboli, accustomed to the hardship of life in Calabria, New South Wales appeared a land of hope and opportunity.

The vegetables and fruit trees Domenico planted on his two-acre holding were enough to support Saveria and the three young children they had brought with them from Italy. It didnt take long for Trimbolinow known as Domenic, and a naturalised Australian citizento pick up the language as he travelled around Bagtown selling his prize cauliflowers from the back of a horse-drawn cart.

Like their father, the children soon acquired Australian names: Joe (the first born), Josie and Elizabeth. All three were well-behaved children who adapted well to their new country, which was slower to adapt to them. The olive-skinned Calabrian and Sicilian migrants were commonly referred to by Australians as dagoes or wogs, their family traditions and customs viewed with suspicion by the districts Anglo-Saxon pioneers.

In the cane fields of far north Queensland, Calabrian men bound to the old hierarchical ways had formed clans, intimidating and extorting from their fellow countrymen, burning the crops and poisoning the livestock of those who refused to pay. Further resistance was met with bombings, woundings and murder. Although the Queensland cane fields lay thousands of kilometres from the orchards and gardens of the Murrumbidgee Irrigation Area, news of the violence spread quickly among the migrant families in Griffith. They could leave Italy but they could not escape the mafia.

On 26 January 1932 Rocco Trimarchi, who had moved to New South Wales after several years on the cane fields, was shot dead at his farm in Griffith. Trimarchis son, Samuel, was convicted of the murder, although an autopsy found that two guns of different calibres had been used. Regarded by police as having been the head of a branch of the Camorra Society, the elder Trimarchi was Griffiths first godfather.

Several Italian men witnessed the shooting but a police report noted that nearly all of them gave different evidence to that in their statementswhich showed that they had been instructed in what to say by some person in the meantime. Was Rocco Trimarchis murder the result of a family feud? Was it an honour killing? Those who knew were not saying.

Domenic and Saveria Trimbolis second son, Bruno, was born on 19 March 1931. The first of the Trimboli children to be born in Australia, Bruno was a happy-go-lucky boy, average at school and with no obvious talents to set him apart from the other Italian kids in a country town full of Italian kids. His parents worried for his future. Older brother Joe was destined for the army and sisters Josie and Betty were expected, like the daughters of other Italian families, to find good husbands. But where did that leave Bruno?

It was obvious that the Trimbolis two-acre farm would not be enough to support Bruno as well as his parents. For a young man in a country town, the only financial security seemed to lie in a trade. But Bruno had no desire to spend the rest of his life as a plumber or a painter. Nor did he have much interest in getting a job in a bank or post office.

As a child, Bruno Trimboli had done his share of chipping weeds and picking vegetables, working ten to twelve hours a day from sun-up to sundown. Bruno was not afraid of physical work but hard labour under the hot Australian sun was not his idea of a future. While his schoolmates settled down to work on their family farms, Bruno decided to seek his fortune in the city.

In Sydney wartime memories were still fresh enough for an Italian name to be a handicap, so Bruno Trimboli adopted the name Robert, which became the quintessentially Australian Bob. At the same time he changed his surname, from Trimboli to Trimbole. With the new name came a new job as an apprentice mechanic at Pioneer Tours.

Affable and easy going, Bob Trimbole had no trouble making friends. Aussie Bob, as some were already calling him, also started to make a name for himself as a gambler, but for that he needed a steady supply of cash. While his days were spent working on bus engines, nights found Bob playing two-up and baccarat in Sydneys illegal gambling dens. Many of the illegal games were run by starting price (or SP) bookies. Somebody at the game was always good for a tip, a sure thing crying out for a punt, and it wasnt long before Aussie Bob was a fixture at the track.

Bob was not a big drinker. Until the mid-1920s alcohol had been prohibited in the Murrumbidgee Irrigation Area and many of the migrant families had grown used to going without. Bob would drink a beer socially, or have a few glasses of wine with a meal, but he prided himself on his sobriety.

In those days Sydneys pubs and hotels were still governed by the six-oclock lockout, but some landlords found cunning ways to continue trading out of hours: hoisting blackout blinds on windows after 6pm; serving longneck bottles; setting up kegs of beer in back rooms that could only be entered by patrons who knew a special code-knock. In some places regulars sat around tables with tea cups and saucers in front of them, along with glasses of water and ice and a teapot containing a full bottle of Scotch, just in case the police turned up to check on the curfew.

Their ingenuity was matched by the illegal gambling bosses, who set up games in warehouses, fruit-packing sheds and abattoirs. Their cockatoos would pass the word to taxi drivers about where the game was being played. The organisersthere might be two or three in the bigger townshad an uncanny knack of knowing when a police raid was imminent. The police were happy enough to turn a blind eye in return for a few quid.