First published in 2019

Copyright Tom Gilling 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone:(61 2) 8425 0100

Email:

Web:www.allenandunwin.com

ISBN 978 1 76052 843 0

eISBN 978 1 76087 215 1

Set by Midland Typesetters, Australia

In memory of

John Manchester

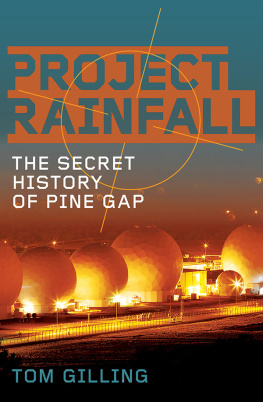

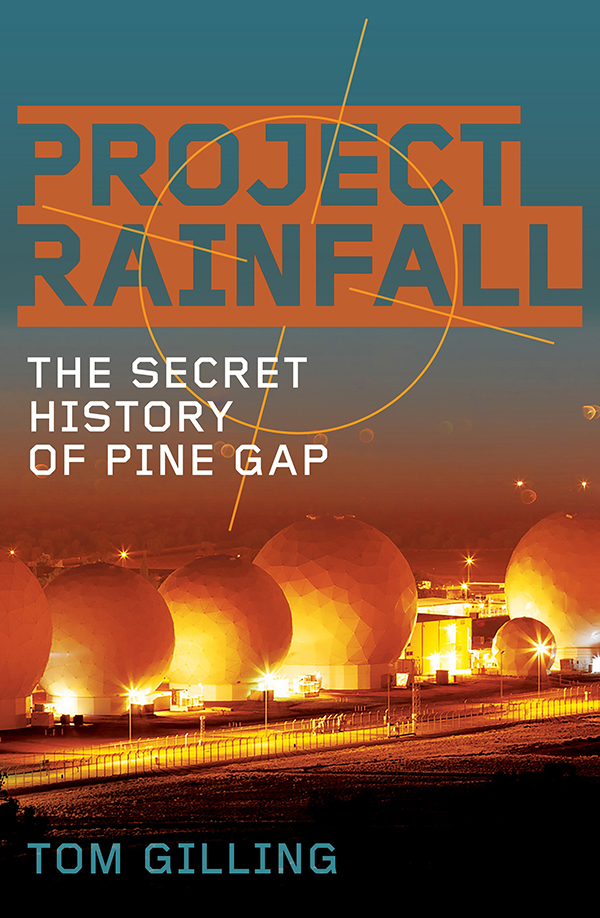

Type the words Pine Gap into Google Earth and it takes you straight there, past the threatening road signs, over the perimeter fence and right up to the door of the top-secret operations building. The site is misnamed Pine Gap Military Facility Australia but there is no mistaking the gleaming white radomes of the place officially known as the Joint Defence Facility Pine Gap.

In the 1960s enterprising journalists and cavalier university lecturers risked arrest and prosecution to get close enough to count the proliferating radomes (Gough Whitlam was allowed to visit in 1969 and miscounted them) but today you can zoom in close enough to do it on your laptop.

During the Cold War, when Pine Gaps main task was keeping an eye on Soviet missiles, peace protesters regularly made the trip to central Australia to demonstrate at the base, with activists leading police and security guards a merry dance behind the wire after breaking in with wirecutters. Since then, Pine Gap has become a vital cog in the American military machine, providing real-time battlefield information to commanders on the ground and locating targets for assassination by US drones.

Once the subject of intense political debate, Pine Gap often goes unmentioned in the Australian parliament for weeks on end. The euphemisms used to obscure its secret purposevague references to its critical contribution to the security of both Australia and the UShave scarcely changed in five decades.

No-one demurred when the defence minister, Christopher Pyne, declared in the House of Representatives on 20 February 2019 that Pine Gap represents one of the finest examples of collaboration, innovation and integration, and has delivered remarkable intelligence dividends to both our nations. No-one pressed Pyne on the new demands and new challenges facing Pine Gap or asked why it was still necessary that relatively few people knew what happened there. On the contrary, the Labor opposition replied that it supports every word the minister has said.

One person who knew what happened at Pine Gap was the late Professor Des Ball, who died in 2016, a few months before I began researching this book. Parliamentary committees frustrated by government stonewalling about Pine Gap and other US bases always knew who to call for accurate and up-to-date information.

Drawing on the technical analysis done by Ball and his colleagues at the ANUs Strategic and Defence Studies Centre, and on interviews and recently declassified documents from both Australian and US archives, Project Rainfall tells the story of Pine Gap from its genesis in the minds of Americas Cold War intelligence chiefs to its modern role as a weapon in the Pentagons war on terror.

Insiders who have written about Pine Gap have had to submit to heavy censorship, while foreign whistleblowers such as Edward Snowden have been threatened with long jail sentences. More than five decades after the signing of the Pine Gap treaty, it remains true that the story of Australias most secret place can only be written from the outside.

The detonation of the first Soviet hydrogen bomb on 12 August 1953 sent shockwaves rippling far beyond the test site on the remote Kazakhstan steppe. The test, known as Joe-4 (it was the fourth Soviet nuclear test announced by the Americans), had an explosive power of roughly 400 kilotons of TNTaround 30 times the yield of the Hiroshima bomb. Although much less powerful than US thermonuclear tests conducted over the Marshall Islands, Joe-4 hadat least according to the Sovietsone big advantage: it was ready for immediate delivery by bomber.

The Americans understood at once the seriousness of the Soviet nuclear threat. The scientific advisory board of the National Security Agency entrusted a special study group to investigate. The top-secret Robertson report, compiled in 1953 and only approved for release in 2013, concluded that a surprise atomic attack on the United States would result in carnage, devastation, psychological shock, and curtailment of our retaliatory ability on a scale difficult to estimate or even to comprehend in terms of any previous experience.

The same year the Continental Defense Committee, chaired by retired General Harold Bull, warned that existing US air defence plans were wholly inadequate and declared the need for strategic warning of a possible Soviet nuclear attack to be so great as to warrant any possible attack on the problem, regardless of its cost, funds and manpower.

Existing radar and ground observer installations could at best give around 30 minutes warning of an attack on coastal targets. Such a warning was only useful for a tactical response, since the attack would already be underway.

What the US government desperately wanted was to stretch the reliable warning period of a Soviet attack from minutes or hours to two or four days. This, it was thought, would give the military time for the complete deployment of our offensive and defensive forces, which would increase the chance of turning the enemys operation before its mission had been accomplished and might even induce the enemy to abandon the attack.

The US air defence system as it existed in the early 1950s could not provide such a warning; in fact, previous studies had been undertaken on the understanding that, in the words of the Robertson report, no earlier warning will be available. In order to obtain the desired early warning of Soviet attack, the US realised it would have to turn to other sources of intelligence. As in the past, these could be divided into overt, covert and signals intelligence. While traditional overt and covert intelligence should be vigorously cultivated, the Robertson report warned that to rely on them would be to court disaster.

Signals intelligenceabove all COMINT [communications intelligence]was judged to be the most promising source of strategic warning of an impending attack on the continental United States. Interception of high-level cryptographic systems and their exploitation on a timely basis therefore became the primary recommendation of the Robertson report.

The strategic importance of signals intelligence had been repeatedly shown during the Second World War, with the interception of high-level Japanese and German messages allowing the Allies to penetrate the enemy lines, enter government ministries and military headquarters, and gain vital early warning of impending operations. According to the CIAs History of SIGINT [signals intelligence] in the Central Intelligence Agency, 194770, Japanese and German military communications and secret diplomatic communications were an open book to the US Government, while the Battle of Britain, the invasion of Europe, the war in Africa, and the Pacific war were all fought to a large extent with prior knowledge of enemy capabilities and intentions attained through US-UK COMINT.