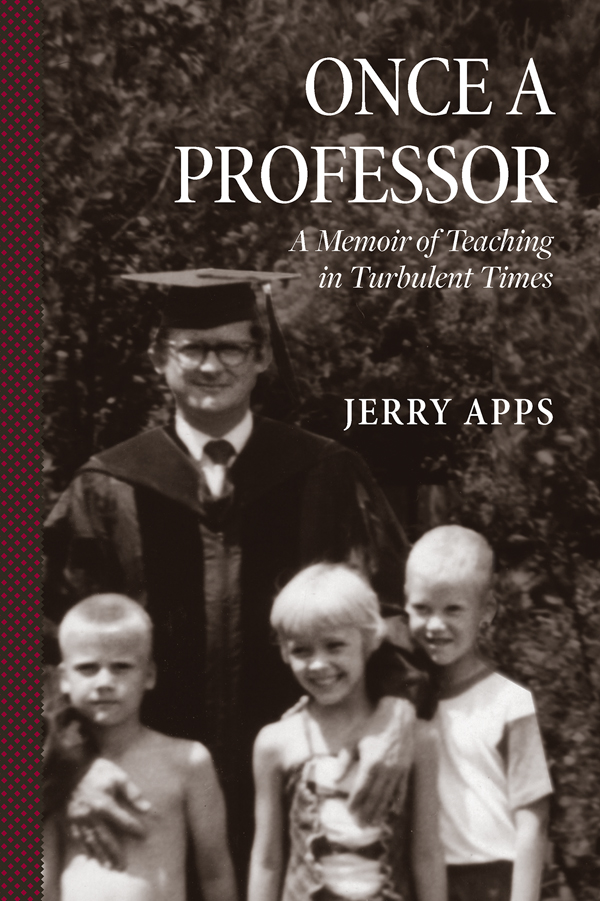

ONCE A PROFESSOR

Once a Professor

A Memoir of Teaching in Turbulent Times

JERRY APPS

Wisconsin Historical Society Press

Published by the Wisconsin Historical Society Press

Publishers since 1855

The Wisconsin Historical Society helps people connect to the past by collecting, preserving, and sharing stories. Founded in 1846, the Society is one of the nations finest historical institutions.

Join the Wisconsin Historical Society: wisconsinhistory.org/membership

2018 by Jerold W. Apps

E-book edition 2018

For permission to reuse material from Once a Professor (ISBN 978-0-87020-857-7; e-book ISBN 978-0-87020-858-4), please access www.copyright.com or contact the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. (CCC), 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400. CCC is a not-for-profit organization that provides licenses and registration for a variety of users.

All photos are from the authors collection unless otherwise credited.

Photographs identified with WHI or WHS are from the Societys collections; address requests to reproduce these photos to the Visual Materials Archivist at the Wisconsin Historical Society, 816 State Street, Madison, WI 53706.

Designed by Diana Boger

22 21 20 19 18 1 2 3 4 5

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Apps, Jerold W., 1934 author.

Title: Once a professor : a memoir of teaching in turbulent times / Jerry Apps.

Description: Madison, Wisconsin : Wisconsin Historical Society Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2017037407 (print) | LCCN 2017044974 (e-book) | ISBN 9780870208584 (E-book) | ISBN 9780870208577 (Hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Apps, Jerold W., 1934 | College teachersUnited StatesBiography. | University of WisconsinMadisonHistory.

Classification: LCC LA2317.A63 (e-book) | LCC LA2317.A63 A3 2018 (print) | DDC 378.12092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017037407

For Professor Walter Bjoraker, my undergraduate advisor

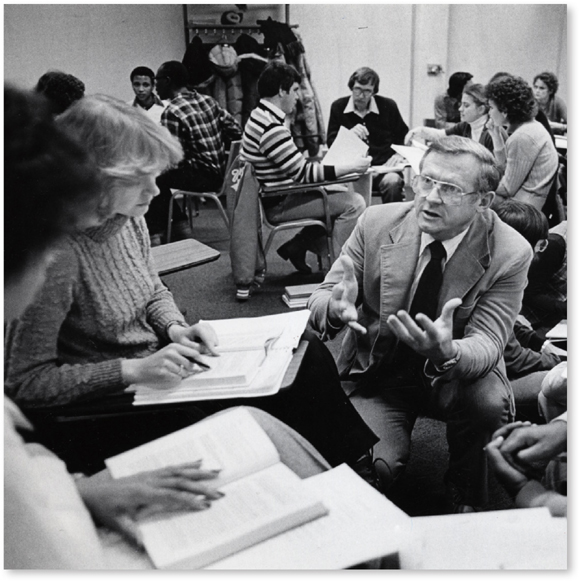

Courtesy of the UWMadison Archives, #S10345

Contents

I never wanted to be a college professor. As a kid growing up on a farm, I had met only one professor, a slow-talking old man who taught at a small Ohio college and spent his summers on the family farm near Wild Rose. He didnt say much, and when he did speak I usually couldnt understand what he said. The people around Wild Rose found him odd. To me he seemed a little strangeand a lot boring.

When I was in grade school, I thought it might be fun to teach in a one-room country school like the one I attended. Then, after I was struck with polio during the winter I was in eighth grade, I began reading everything I could get my hands onnovels, history, biographies, poetry. I would never play high school sports or participate in vigorous physical activities like the other kids in my class, so instead I studied a lot, edited the high school newspaper, and entered speaking contests. I even learned to enjoy public speaking (thanks to my time announcing basketball games at Wild Rose High School), and I thought I might want to teach high school agriculture one day. Still, the idea of being a professor never crossed my mind.

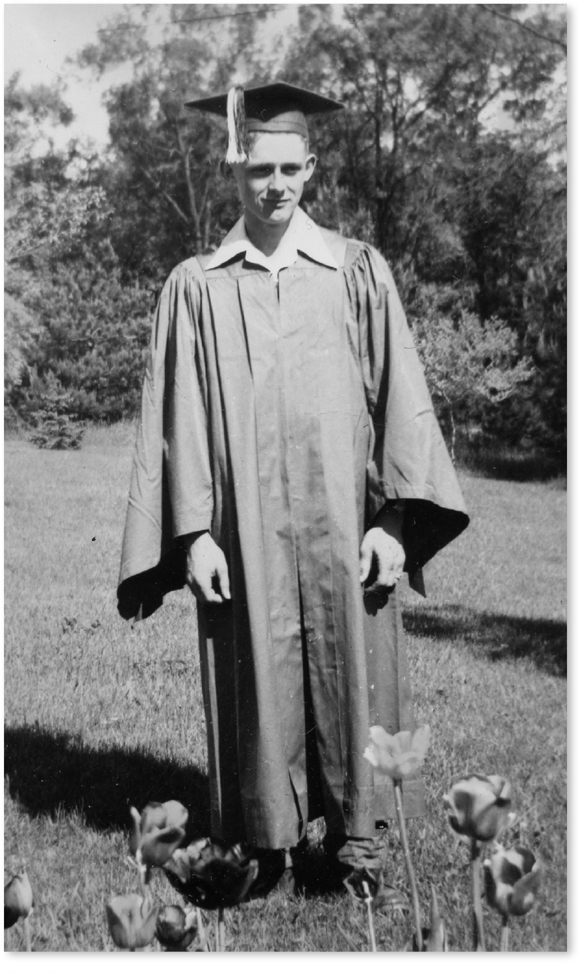

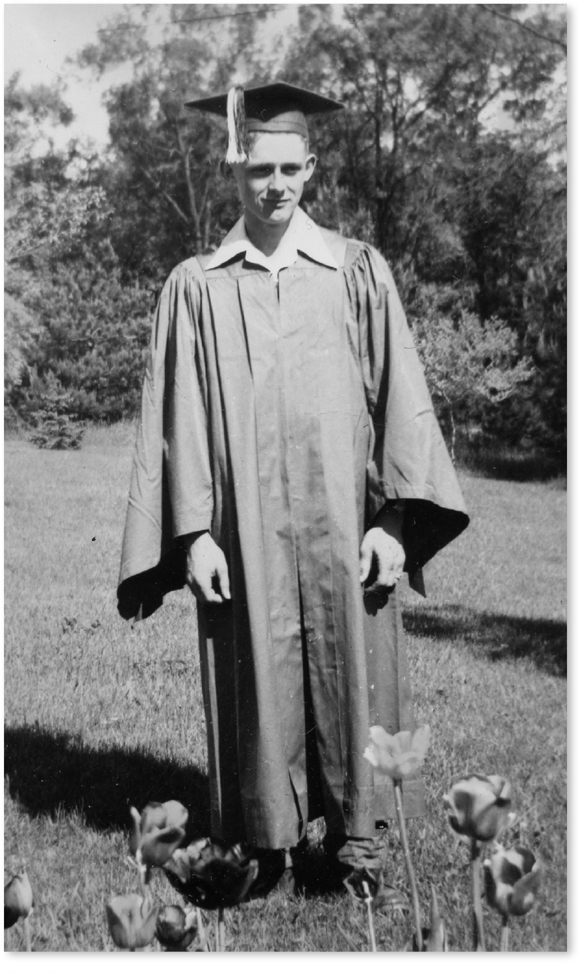

Here I am as a sixteen-year-old high school graduate, about to leave home for Madison.

I enrolled at the University of WisconsinMadison in the College of Agriculture for the fall semester of 1951 as a new freshman. I had just turned seventeen. I was alone in the big city, and I was scared to death. I had never lived in a city, and I knew no one. I liked the quiet of the country, the country smells and sounds, and the feelings that went along with country life.

I had graduated from Wild Rose High School that spring at the age of sixteen. To my great surprise, as valedictorian of my class I had earned a tuition scholarship to attend the states big university (as people referred to it in those days). My scholarship was worth $63.50, which, as my dad said, was a lot of money. Times were tough on the home farm during the early 1950s, and I had given little thought to attending college. Without the scholarship I never would have been able to go.

Along with carrying a full-time class load, I worked forty hours a week so I could earn enough money to cover my expenses. I rented a room for five dollars a week, cooked most of my meals there, and studied. I had little time or money for social activities other than study groups. To those interested in college social life, I must have appeared to be the most boring guy theyd ever met.

But I was enjoying every minute of it. I was awash in new ideas that challenged me to think about things I had never thought about. I liked getting to know my professors, who had vocabularies that far exceeded mine and ideas I had never considered.

The Korean Conflict had begun in 1950, and at the UW I enrolled in the Reserve Officers Training Corps, a requirement for all male freshmen. No army doctor ever asked me if I had had polio, and I didnt volunteer the information. I suspect I could have gotten a medical deferment, but I didnt want one. Neverthless, ROTC duty provided a deferment from the draft. It also provided ample opportunities for marching, which helped strengthen my weak leg.

After four years in ROTC, I received a commission as a second lieutenant in the US Army Reserve and was expected to go on active duty for two years upon graduation in 1955. By then I had earned a teaching certificate, which would allow me to teach vocational agriculture and biology in any Wisconsin high school. But army service came first.

While serving on active duty in the military at Fort Eustis, Virginia, I had little to do, as the hostilities in Korea had ceased in 1953. I was assigned to the 507th Transportation Battalion, moving people from here to there. When I had finished my days assignment, I drank coffee at the PX, chatted with my fellow second lieutenants, and did a lot of thinking about my future plans. I decided that teaching in a high school classroom wasnt really what I wanted to do. I had practice-taught at five high schools while earning my teaching certificate, and to me the work seemed too confining, too caught up in rules and regulations.

I thought about working in a business related to agriculture, maybe for a feed or implement company. They were always looking for college graduates with farm backgrounds. I also considered returning to the home farm, where I knew my parents could use my help. My two-year army obligation was down to six months, with six years of reserve duty to follow, and the army had more second lieutenants than it needed. So what would I do next?

In the summer of 1956, when I was released from active military duty, I stopped in Madison to see my undergraduate advisor, Professor Walter Bjoraker, chair of UWMadisons Department of Agricultural and Extension Education. We chatted for a time, and then, out of the blue, Professor Bjoraker asked me, Would you be interested in working on a masters degree?

Graduate work was something I had never considered. Maybe, I replied. Working on my masters would give me a year to make up my mind about my career options.