Published by the Wisconsin Historical Society Press

Publishers since 1855

2013 by Jerold W. Apps

E-book edition 2013

For permission to reuse material from Limping through Life (ISBN 978-0-87020-580-4, e-book ISBN 978-0-87020-587-3), please access www.copyright.com or contact the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. (CCC), 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400. CCC is a not-for-profit organization that provides licenses and registration for a variety of users.

www.wisconsinhistory.org

All photos are from the authors collection unless otherwise credited.

Photographs identified with WHi or WHS are from the Societys collections; address requests to reproduce these photos to the Visual Materials Archivist at the Wisconsin Historical Society, 816 State Street, Madison, WI 53706.

Cover design by Percolator Graphic Design

Interior design, typesetting, and e-book design by Ryan Scheife, Mayfly Design

17 16 15 14 13 1 2 3 4 5

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Apps, Jerold W., 1934

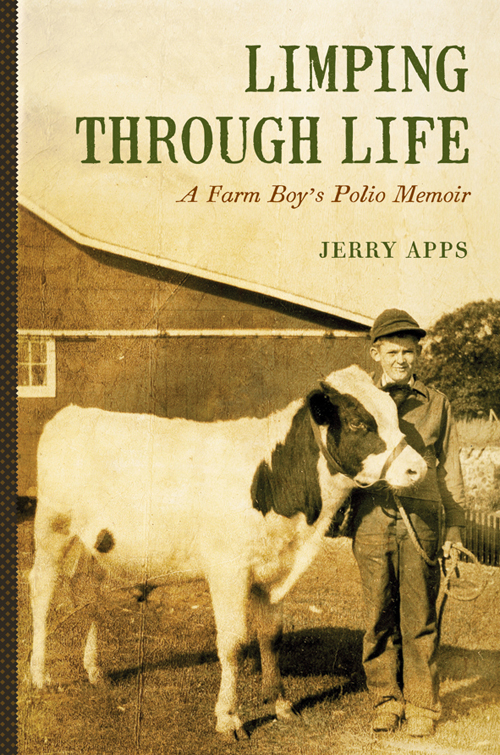

Limping through life : a farm boys polio memoir / Jerry Apps.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-87020-580-4 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Apps, Jerold W., 1934Health. 2. PoliomyelitisPatientsWisconsinBiography. I. Title.

RC180.2.A67 2013

616.8350092dc23

[B]

2012032704

To Herman and Eleanor Apps, my parents, and Faith Jenks,

my eighth grade teacher, who through their encouragement

and caring got me through my worst days with polio.

Contents

Preface

Polio is rarely talked about today, especially in the United States. Yet those of us who had the disease remember it all too well. In the 1940s and 1950s, before a vaccine was developed, polio dashed hopes, generated near terror in communities throughout the country, caused untold anguish for victims and their families, and dramatically changed the lives of those who contracted it.

The years just after World War II, roughly 1946 to 1955, were the peak years for polio outbreaks in this country. Wisconsin had one of its worst epidemics in 1955, when the state reported 921 cases and 134 deaths due to polio by August. The worst year for polio in the United States was 1952, when 60,000 cases were reported nationwide.

Also known as poliomyelitis or infantile paralysis, polio is an infectious viral disease that most commonly attacks children, more boys than girls. Before the cause and spread of the disease were understood, many people incorrectly thought it was spread by sneezing and coughing, like many influenza viruses. Researchers ultimately determined that polio is caused by a virus that enters the body through the mouth and moves into the intestinal tract. The main breeding ground for the virus is the small intestine. The disease spreads from person to person by unwashed hands after using the bathroom or through contaminated food and water.

Testing began on Jonas Salks polio vaccine in 1952. But the vaccine would not be widely available until 1955, and even after that time people lived in fear of contracting the disease. Not knowing how the disease was transmitted resulted in a near panic in some communities. Swimming pools were closed, county fairs cancelled, family picnics postponed. People feared going anywhere there was a crowd.

Today people often ask me how I got polio. I have no idea. I was the only one at my school to come down with the disease. Neither of my brothers got itperhaps because my folks kept them away from me almost immediately after my symptoms appeared. One boy from a nearby school district had died from polio a few months before I became ill, but I had not been in contact with him. Several other children in and around my hometown of Wild Rose had polio, but I had no contact with them either.

Little did I know at the time that I contracted polio what a profound effect it would have on me for the rest of my life, both physically and emotionally. I also had no way of knowing how it would affect my brothers and my parents. Families throughout the United States lived in fear of polio throughout the late 1940s and early 1950s, and now the disease had come to our farm. I can still remember that short winter day and the chilly night when I first showed symptoms. My life would never be the same.

Amanda Boeker and Valerie Brandt, Living in Fear: Northeast Wisconsins Polio Epidemics, Voyageur, Winter/Spring 2007, 10.

1 First Symptoms

It came in the night, unannounced and unexpected. Just as the first November snowfall can transform the landscape in only an hour or two, the events of that evening in January 1947 would change my life profoundly.

I was twelve years old and the only student in eighth grade at the Chain O Lake School, a mile south of our Waushara County farm. My twin brothers, Donald and Darrel, were nine years old and in fourth grade at the same school. The three of us walked home that afternoon with Marvin Miller, whose farm was just south of ours, and Lyle York, who lived three-quarters of a mile beyond our place.

Snow blanketed the countryside, three feet or deeper everywhere. The snowplows that rumbled by our farm after each storm that winter had piled the snowbanks high, and walking along the snow-packed, narrow country road was like walking in a tunnel without a top. We pulled our sleds behind us. After several days of below-zero weather, the temperature had climbed into the twenties that day, and it had been a good day for sledding on the long hill west of our schoolyard, on Lizzie Hatliffs land, during recess and our noon break. There had been lots of laughter, many spills, and several racesthe kids with Flexible Flyer sleds usually won. My cheap hardware store sled served me well, but it lost most races.

Wicked snowstorms often buried our farm, making travel impossible and chores a challenge.

At home we changed our clothes and began doing our afternoon chores. Being the oldest, I did barn chores with Pa: throwing down hay from the haymow, tossing corn silage from the silo, feeding the cows, and carrying in straw from the straw stack for bedding the animals. My brothers fed the chickens, gathered eggs, and hauled in wood for our two always-hungry woodstoves, one in the kitchen and one in the dining room. More chores waited for after supper.

We sat at our regular places around the kitchen table, Ma on one end, closest to the wood-burning cookstove, Pa at the other end, and me across from my two brothers. Just as the cows in our barn always stood in the same stall, our positions at the table never changed. The kerosene lamp had a prominent place in the middle of the big wooden table covered with a red-checked oilcloth. Its soft yellow light cast long shadows on the plain white walls of our farm kitchen. Electricity would not come to our farm until later that spring.

Our supper meal was plain but filling: fried potatoes, ham prepared in a milk-flour mixture (a smoked ham always hung on the wall of the cellar steps), steaming sauerkraut (a crock of the pungent cabbage concoction stood in the corner of the pantry), home-canned peas or corn, and applesauce or canned peaches for dessert.