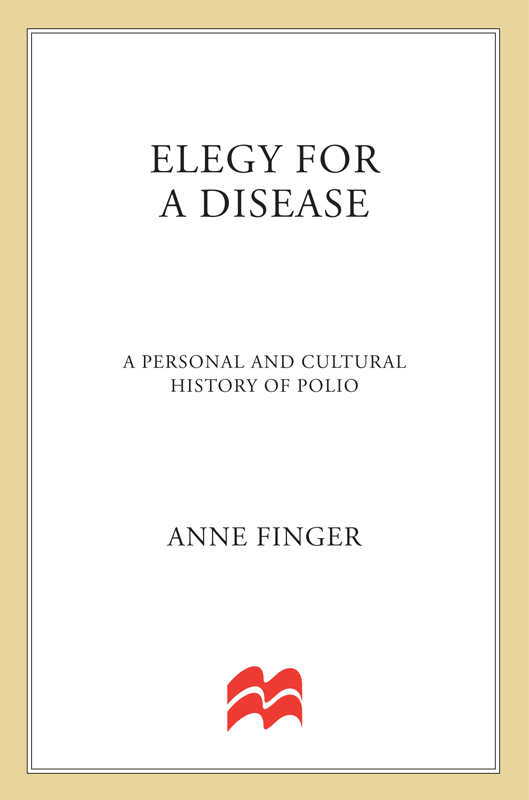

Anne Finger - Elegy for a Disease: A Personal and Cultural History of Polio

Here you can read online Anne Finger - Elegy for a Disease: A Personal and Cultural History of Polio full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2013, publisher: St. Martins Publishing Group, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Elegy for a Disease: A Personal and Cultural History of Polio

- Author:

- Publisher:St. Martins Publishing Group

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

Elegy for a Disease: A Personal and Cultural History of Polio: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Elegy for a Disease: A Personal and Cultural History of Polio" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

During the first half of the twentieth century, epidemics of polio caused fear and panic, killing some who contracted the disease, leaving others with varying degrees of paralysis. The defeat of polio became a symbol of modern technologys ability to reduce human suffering. But while the story of polio may have seemed to end on April 12, 1956, when the Salk vaccine was declared a success, millions of people worldwide are polio survivors.

In this dazzling memoir, Anne Finger interweaves her personal experience with polio with a social and cultural history of the disease. Anne contracted polio as a very young child, just a few months before the Salk vaccine became widely available. After six months of hospitalization, she returned to her familys home in upstate New York, using braces and crutches. In her memoir, she writes about the physical expansiveness of her childhood, about medical attempts to fix her body, about family violence, job discrimination, and a life rich with political activism, writing, and motherhood.

She also writes an autobiography of the disease, describing how it came to widespread public attention during a 1916 epidemic in New York in which immigrants, especially Italian immigrants, were scapegoated as being the vectors of the disease. She relates the key roles that Franklin Roosevelt played in constructing polio as a disease that could be overcome with hard work, as well as his ties to the nascent March of Dimes, the prototype of the modern charity. Along the way, we meet the formidable Sister Kenny, the Australian nurse who claimed to have found a revolutionary treatment for polio and who was one of the most admired women in America at mid-century; a group of polio survivors who formed the League of the Physically Handicapped to agitate for an end to disability discrimination in Depression-era relief projects; and the founders of the early disability-rights movement, many of them polio survivors who, having been raised to overcome obstacles and triumph over their disabilities, confronted a world filled with barriers and impediments that no amount of hard work could overcome.

Anne Finger writes with the candor and the skill of a novelist, and shows not only how polio shaped her life, but how it shaped American cultural experience as well.

Anne Finger: author's other books

Who wrote Elegy for a Disease: A Personal and Cultural History of Polio? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.