Anniversary Edition

Small Steps:

THE YEAR I GOT POLIO

Peg Kehret

Albert Whitman & Company

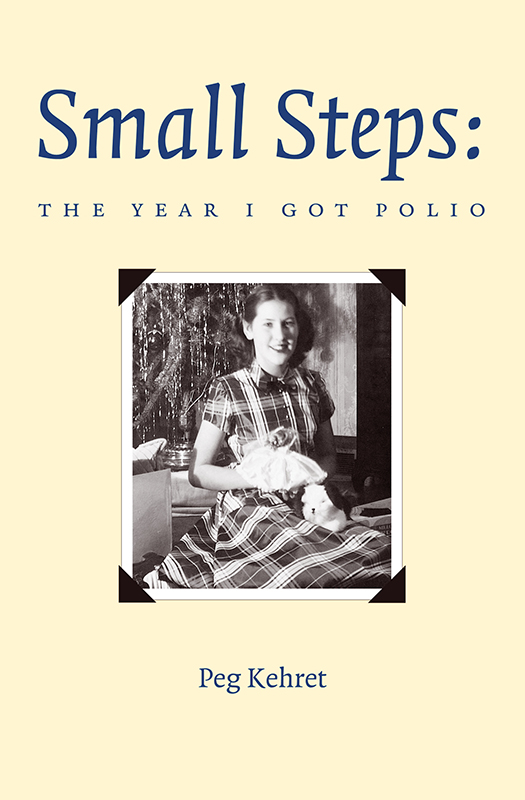

Me at twelve, just before I got polio.

For my parents: Beth and Bob Schulze.

W hen I began to write about my polio days, long-forgotten memories bubbled to the surface. I was astonished by the intense emotions these memories brought with them. Those months, more than any other time of my life, molded my

personality.

Since I have no transcript of these events, the dialogue is not strictly accurate, but the people mentioned are all real

people. The incidents all happened, and the voices are as close to reality as I can make them.

Peg Kehret

1: The Diagnosis

I never thought it would happen to me. Before a polio vaccine was developed, I knew that polio killed or crippled thousands of people, mainly children, each year, but I never expected it to invade my body, to paralyze my muscles.

Polio is a highly contagious disease. In 1949, there were 42,033 cases reported in the United States. One of those was a twelve-year-old girl in Austin, Minnesota:

Peg Schulze. Me.

My ordeal began on a Friday early in September. In school that morning, I glanced at the clock often, eager for the Homecoming parade at four oclock. As a seventh-grader, it was my first chance to take part in the Homecoming fun. For a week, my friends and I had spent every spare moment working on the seventh-grade oat, and we were sure it would win first prize.

My last class before lunch was chorus. I loved to sing, and we were practicing a song whose lyrics are the inscription on the Statue of Liberty. Usually the words Give me your tired, your poor brought goosebumps to my arms, but on Homecoming day, I was distracted by a twitching muscle in my left thigh. As I sang, a section of my blue skirt popped up and down as if jumping beans lived in my leg.

I pressed my hand against my thigh, trying to make the muscle be still, but it leaped and jerked beneath my ngers. I stretched my leg forward and rotated the ankle. Twitch, twitch . Next I tightened my leg muscles for a few seconds and then relaxed them. Nothing helped.

The bell rang. When I started toward my locker, my legs buckled as if I had nothing but cotton inside my skin. I collapsed, scattering my books on the oor.

Someone yelled, Peg fainted, but I knew I had not fainted because my eyes stayed open and I was conscious. I sat on the oor for a moment.

Are you all right? my friend Karen asked as she helped me stand up.

Yes. I dont know what happened.

You look pale.

Im fine, I insisted. Really.

I put my books in my locker and went home for lunch, as I did every day.

Two days earlier, Id gotten a sore throat and head-ache. Now I also felt weak, and my back hurt. What rotten timing, I thought, to get sick on Homecoming day.

Although my legs felt wobbly, I walked the twelve blocks home. I didnt tell my mother about the fall orabout my headache and other problems because I knew she would make me stay home.

I was glad to sit down to eat lunch. Maybe, I thought, I should not have stayed up so late the night before. Or maybe Im just hungry.

When I reached for my milk, my hand shook so hard I couldnt pick up the glass. I grasped it with both hands; they trembled so badly that milk sloshed over the side.

Mother put her hand on my forehead. You feel hot, she said. Youre going straight to bed.

It was a relief to lie down. I wondered why my back hurt; I hadnt lifted anything heavy. I couldnt imagine why I was so tired, either. I felt as if I had not slept in days.

I fell asleep right away and woke three hours later with a stiff neck. My back hurt even more than before, and now my legs ached as well. Several times I hadpainful muscle spasms in my legs and toes. The muscles tightened until my knees bent and my toes curled, and I couldnt straighten my legs or toes until the spasms passed.

I looked at the clock; the Homecoming parade started in fteen minutes.

I want to go to the parade, I said.

Mother stuck a thermometer in my mouth, said, One hundred and two, and called the doctor. The seventh-grade oat would have to win rst place without me. I went back to sleep.

Dr. Wright came, took my temperature, listened to my breathing, and talked with Mother. Mother sponged my forehead with a cold cloth. I dozed, woke, and slept again.

At midnight, I began to vomit. Mother and Dad helped me to the bathroom; we all assumed I had the u.

Dr. Wright returned before breakfast the next morning and took my temperature again. Still one hundred and two, he said. He helped me sit up, with my feet dangling over the side of the bed. He tapped my knees with his rubber mallet; this was supposed to make my legs jerk. They didnt. They hung limp and unresponsive.

I was too woozy from pain and fever to care.

He ran his ngernail across the bottom of my foot, from the heel to the toes. It felt awful, but I couldnt pull my foot away. He did the same thing on the other foot, with the same effect. I wished he would leave me alone so I could sleep.

I need to do a spinal tap on her, he told my parents. Can you take her to the hospital right away?

Dad helped me out of bed. I was too sick to get dressed.

At the hospital, I lay on my side while Dr. Wright inserted a needle into my spinal column and withdrew some uid. Although it didnt take long, it was painful.

The laboratory analyzed the uid immediately. When Dr. Wright got the results, he asked my parents to go to another room. While I dozed again, he told them the diagnosis, and they returned alone to tell me.

Mother held my hand.

You have polio, Dad said, as he stroked my hair back from my forehead. You will need to go to a special hospital for polio patients, in Minneapolis.

Polio! Panic shot through me, and I began to cry. I had seen Life magazine pictures of polio patients in wheelchairs or wearing heavy iron leg braces. Each year the March of Dimes, which raised money to aid polio patients and fund research, printed a poster featuring a child in a wheelchair or wearing leg braces or using walking sticks. The posters hung in stores, schools, and librariesfrequent reminders of the terrible and lasting effects of polio. Everyone was afraid of polio. Since the epidemics usually happened in warm weather, children were kept away from swimming pools and other crowded public places every summer because their parents didnt want them exposed to the virus.

How could I have polio? I didnt know anyone who had the disease. Where did the virus come from? How did it get in my body?

I didnt want to have polio; I didnt want to leave my family and go to a hospital one hundred miles away.

As we drove home to pack, I sat slumped in the back seat. How long will I have to stay in the hospital? I asked.

Until youre well, Mother said.

I caught the look of dread and uncertainty that passed between my parents. It might be weeks or months or even years before I came home. It might be never; people sometimes died from polio.

That fear, unspoken, settled over us like a blanket, smothering further conversation.

When we got home, I was not allowed to leave the car, not even to say good-bye to Grandpa, who lived with us, or to B.J., my dog. We could not take a chance of spreading the deadly virus. Our orders were strict: I must contaminate no one.

Karen called, Mother said when she returned with

a suitcase. The seventh-grade oat won second prize.

Next page