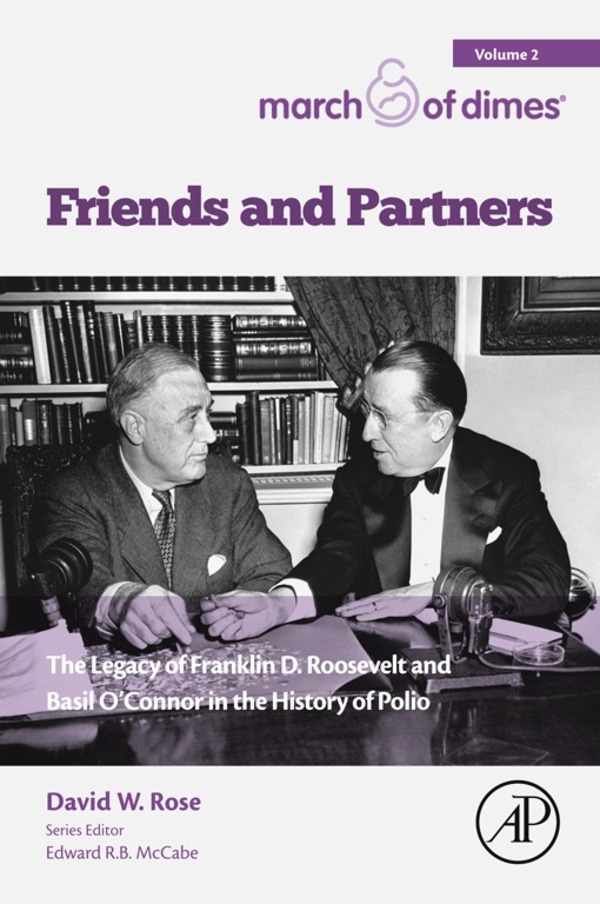

Friends and Partners

The Legacy of Franklin D. Roosevelt and Basil OConnor in the History of Polio

David W. Rose

Series Editor

Edward R. B. M C cabe

March of Dimes Foundation

Table of Contents

Copyright

Academic Press is an imprint of Elsevier

125 London Wall, London EC2Y 5AS, UK

525 B Street, Suite 1800, San Diego, CA 92101-4495, USA

50 Hampshire Street, 5th Floor, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA

The Boulevard, Langford Lane, Kidlington, Oxford OX5 1GB, UK

Copyright 2016 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Details on how to seek permission, further information about the Publishers permissions policies and our arrangements with organizations such as the Copyright Clearance Center and the Copyright Licensing Agency, can be found at our website: www.elsevier.com/permissions.

This book and the individual contributions contained in it are protected under copyright by the Publisher (other than as may be noted herein).

Notices

Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broaden our understanding, changes in research methods, professional practices, or medical treatment may become necessary.

Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluating and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein. In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility.

To the fullest extent of the law, neither the Publisher nor the authors, contributors, or editors, assume any liability for any injury and/or damage to persons or property as a matter of products liability, negligence or otherwise, or from any use or operation of any methods, products, instructions, or ideas contained in the material herein.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN: 978-0-12-803597-9

For information on all Academic Press publications visit our website at https://www.elsevier.com/

Typeset by TNQ Books and Journals

www.tnq.co.in

Dedication

In Memory of Charles L. Massey (19222015)

President of the March of Dimes (19781989)

Foreword

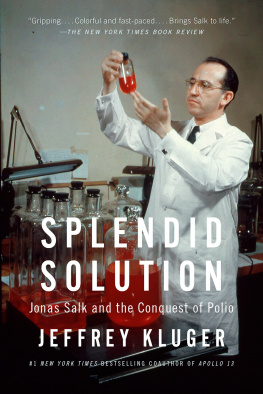

Most Americans today know little about polioand thats surely what Basil OConnor would have wanted. The disease he fought so hard to conquer is now a relic of history, banished to isolated corners of the globe, on the brink of eradication. It was not an easy fight. Those who lived through the polio years well remember the fear it generated and the suffering it caused. The battle had an iconic symbol in Franklin Roosevelt, a battalion of brilliant scientists led by Albert Sabin and Jonas Salk, and an army of dedicated March of Dimes volunteers. Largely ignored, however, is the field general who molded this talent and energy into a stunning national crusade. The full story of Basil OConnors central role in defeating polio, deftly told here by David Rose, is long overdue.

Polio is an intestinal infection that spreads from person to person through oralfecal contact: unwashed hands, contaminated food or water, or shared objects. The agent is a virus that enters the body through the mouth, travels down the digestive tract, and is excreted in the bowels. Usually the infection it produces is slighta headache, slight fever, nauseathough the victim remains a carrier of the disease. In rare instance the virus enters the bloodstream, invading the brain and central nervous system and destroying the nerve cells that stimulate the muscle fibers to contract. Death most often occurs when the breathing muscles controlled by the brain stem (or bulb) are involved, a condition known as bulbar polio.

Once called infantile paralysis, polio did not appear in epidemic form in the United States until 1916, claiming 6,000 lives, many of them in New York City. Why it came when it did, and why the mass outbreaks occurred almost exclusively in the United States and other developed nations, remains a mystery. Polio in epidemic form is both a modern phenomenon and an affliction of the West.

Some see it as a disease of cleanliness. As Western nations industrialized, they became more health conscious. Clean water, better sanitation, and stricter personal hygiene became hallmarks of modern life. What Americans could not foresee, however, was that their antiseptic revolution brought risks as well as rewards. As these reforms advanced, people were less likely to come into contact with poliovirus early in life, when the infection is milder and maternal antibodies offer temporary protection. The end result would be a vastly expanding pool of victimsthe most famous, of course, being Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR).

When Roosevelt was struck down by polio in 1921, the public response bordered on disbelief. The disease was just taking hold in the United States and the victims were mainly children, as the New York City epidemic of 1916 had so cruelly shown. Yet here was FDR39 years old, robust and athleticat the mercy of a childrens disease, paralyzed from the waist down.

When I was writing Polio: An American Story , my editor asked me to explain how FDR contracted polio. I flippantly (if correctly) replied: He was unlucky. That wouldnt do, of course. I had to provide some background to explain Roosevelts ill fortune.

It was well known that FDR had come of age on an isolated estate in the Hudson Valley. He had been sheltered by a small army of nannies and tutors, interacting with adults and avoiding the common childhood illnesses until his arrival at boarding school. From that point forward, I wrote, his medical history resembled an encyclopedia of contagious diseases. The list included typhoid fever, swollen sinuses, infected tonsils, and endless sore throats, some of which forced him to bed for weeks. During the influenza pandemic of 191819, Roosevelt contracted a case of double pneumonia that almost took his life. His early years, it appeared, had left him immunologically unprepared for the world beyond Hyde Park.

There was more. The summer of 1921 had been especially hard on himintense, humiliating, and pressure packed. Already drained from a losing campaign for vice president the previous fall, FDR found himself in the middle of a national scandal regarding his role, as assistant secretary, in allegedly using undercover agents to entrap young sailors. It was a bogus charge, politically motivated, but it forced him to testify before Congress in the brutal Washington heat. Exhausted, he set out for the familys retreat at Campobello, in Canadas Bay of Fundy, stopping along the way to attend a massive Boy Scout jamboree at New Yorks Bear Mountain Park. It was here, in all likelihood, that poliovirus entered his body. A poignant photo, one of the last taken of Roosevelt walking unassisted, shows him marching in the scout parade.