Red Kestrel Books 2019, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

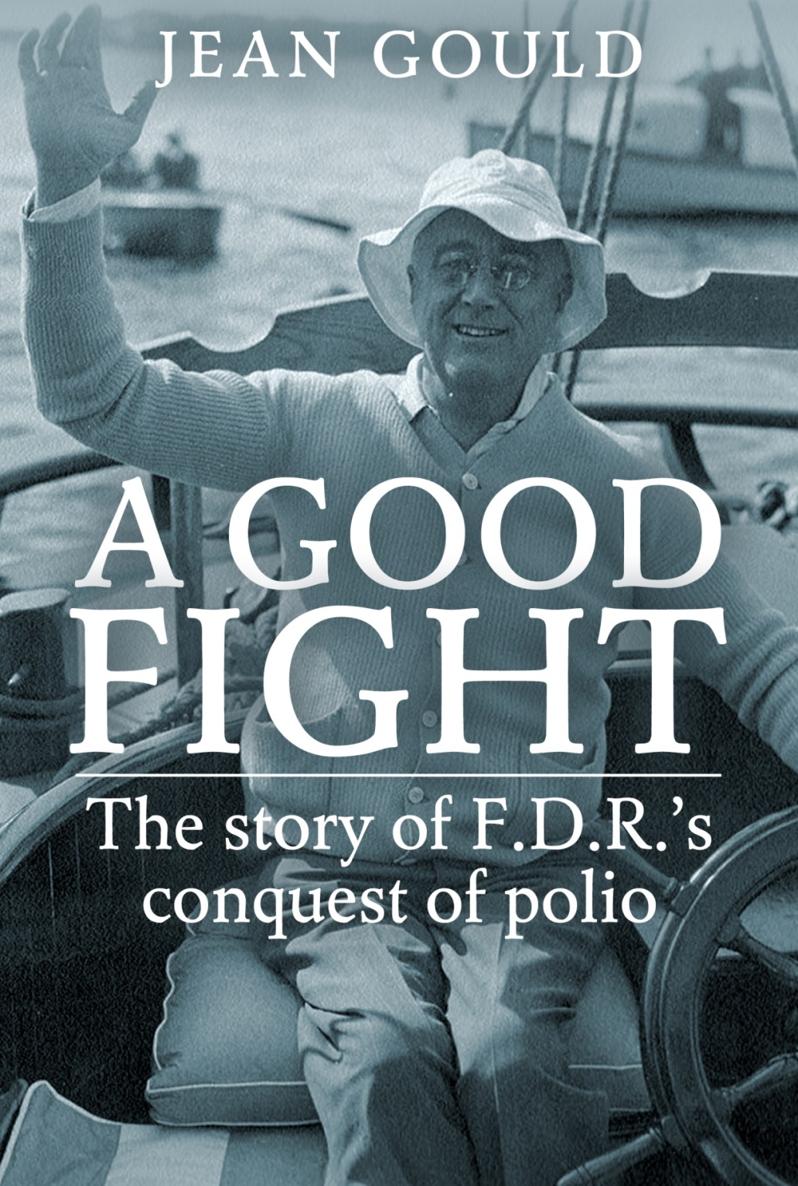

A GOOD FIGHT

The Story of F.D.R.s Conquest of Polio

By

JEAN GOULD

A Good Fight was originally published in 1960 by Dodd, Mead & Company, New York.

To

E.H.D., Jr.

who gave me this book to write

I have fought a good fight,

I have finished my course,

I have kept the faith.II Timothy, iv, 7

Im an old campaigner, and I love a good fight!F.D.R.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The narrative of F.D.R.s victory over polio could not have been written without valuable aid from a number of sources. Particular thanks go to a friend of long standing, Dr. A. L. VanHorn, Medical Director, Kate Macy Ladd Convalescent Home, who checked the medical data in the manuscript; to Dr. Robert L. Bennett, Medical Director of the Georgia Warm Springs Foundation; and to Dr. Salo Rosenbaum, M.D., who helped me to overcome the hardest handicap of allthe one that didnt exist.

I wish also to express my appreciation to Mrs. Eleanor Roosevelt, who was so gracious and helpful in granting interviews; to James Roosevelt; and to Miss Margaret Suckley, cousin of F.D.R., who recalled details of his convalescence at Hyde Park. To her, and to the rest of the staff at the Roosevelt Library, I am most grateful; Dr. Herman Kahn, Director of the library, and Robert Jacoby, research librarian, gave extensive co-operation in furnishing files of material in my field and related subjects.

Mr. Basil OConnor, President of the National Foundation, gave special assistance in contacting the staff at Warm Springs, to whom I owe a vote of gratitudeto Robert Chaplin, Betty Brown, Duncan Cannon, Woodall Bussey, Horace Maddox, and H. M. McRae. (To the last-named I am indebted for much information concerning Roosevelts braces.) Mr. Charles A. Phelan, of the Little White House Memorial Commission, was also most kind and helpful. To all of these, and many others who contributed to my general knowledge of the subject, I offer my appreciation and admiration.

J.G.

CHAPTER I The Attack

On the evening of July 18, 1921, Franklin D. Roosevelt was working tensely to complete a crucial and dramatic statement to the press. It was a quarter to eighthe had fifteen minutes.

He had been given only ten hours to refute the testimony contained in fifteen volumes6,000 pagesof a Senate subcommittee investigating the administration of naval affairs during World War I. Roosevelt, the particular target of the investigation, had been Assistant Secretary of the Navy. At ten oclock that morning, the two Republican Senators, who had already written their majority report without giving him the hearing he requested, had granted him the opportunity to go through the fifteen volumes of testimony and submit a statement by eight oclock in the evening. If he had not been so outraged, he would have laughed in their faces: it was like being told to empty the sea with a sieve. As it was, however, he accepted the challenge. He got hold of Steve Early (who had been one of the advance publicity men in the vice-presidential campaign Roosevelt had made as the running mate of Cox the year before) and they rolled up their sleeves and went to work.

Washington in mid-July is historically hot as a firecracker, and the summer of 1921 was no exception. It was a sweltering day and, as the two men labored through volume after volume of repetitious statements made by the thirty witnesses who had come before the subcommittee, they grew feverish with the heat and mounting indignation. Rooseveltslim, tall, and taut as a live wirekept jumping up every now and then, pacing back and forth in his old office in the Navy Building, which they were using for the study. Overhead a fan buzzed, but it did little more than create a sirocco-like breeze through the room.

Damn it, Steve, this whole business is nothing but dirty politics; thats the point weve got to emphasize. He had been clenching a short-stemmed pipe between his teeth, but now he took it out to punctuate his remarks with short angry jabs at the air.

Early nodded. I get it.

Roosevelt sat down, taking up a pencil and some legal foolscap. Well make that subcommittee look sick.

All day long they had sweated over the mountainous pile of hearings; at lunchtime they had sent out for sandwiches and cold drinks (which had grown tepid by the time the bottles reached the office). Both men had loosened their ties and opened their shirt collars; it must have been one of the hottest days on record...

At four oclock, as the statement was beginning to take shape, the phone rang. It was the reporters: they thought Mr. Roosevelt should know that the majority report was in the hands of all the papers for release the next night and that Senator Ball (the committee chairman) had declined to hold it back or amend it in any way.

Thanks, boys. He hung up, white with anger. The opposition Senators wouldnt even wait to hear him! They probably never expected him to show up at eight oclock; their move proved the futility of trying to get any fair treatment. Well, he would keep on with his statement; and, after he had given it to the majority Senators, he would give it to the press; and he would request an open hearing before the full Senate Committee on Naval Affairs.

The hours ticked by while the two men wrote, consulted the files, crossed out, and rewrote. The sweat rolled off their faces, and their fingers stuck to the copy pencils. After the phone call came, they wrote more with the press in mind than the subcommittee.

As he and Steve finished whipping each paragraph into shape, his secretary, Marguerite LeHandMissy, as she was familiarly knowntyped it into the official statement. Missy, like Steve, had been part of the 1920 vice-presidential campaign staff, and Roosevelt had been so impressed with her efficiency and personality that he had retained her as his private secretary. The three had worked together often during the campaign and were able to co-ordinate their efforts easily now.

The next completed paragraph read, In September, 1919, I, as Acting Secretary, and Captain Leigh, as Acting Chief of the Bureau of Navigation, were, for the first time, informed by two friends of a local Newport minister, who had been tried in a local court and acquitted, that some of the members of the investigating squad had used highly improper and revolting methods in getting evidence. Immediate orders went out from me and Captain Leigh that day to stop it. There is no charge that any wrong-doing occurred after that. That is all there is to the Senators unwarranted deduction.