THE HEALTH OF NATIONS

THE HEALTH OF NATIONS

The Campaign to End Polio and Eradicate Epidemic Diseases

KAREN BARTLETT

For my mother

CONTENTS

The grumpy country doctor, Edward Jenner, changed the course of medicine by vaccinating local villagers in his Temple of Vaccinia, situated in his idyllic English country garden.

INTRODUCTION

A Gloucestershire garden

T ucked away in the farthest corner of a country garden in Gloucestershire sits an unprepossessing summerhouse, shaded and quiet, calmly anchored to the cool English earth. There is scarcely a whisper that, in this spot, scientific innovation shook the world and changed the course of human history. This is the Temple of Vaccinia, a tiny mushroom-shaped building, with bark-covered walls and a thatched roof. Although its silence now speaks of quiet neglect, this was once a hive of activity, with a line of people snaking around the garden, waiting to be vaccinated against smallpox by their local doctor, Edward Jenner.

Edward Jenner was not the first person to understand that exposure to cowpox led to immunity against the far more serious disease of smallpox but he was the first truly to understand the consequences of vaccination and to seek to prove them and publicize it in the medical community. Much to his chagrin, he believed he received insufficient thanks or appreciation for his work in his lifetime. Astonishingly, his reputation derived more from his work in understanding how cuckoo chicks pushed other birds from the nest than from being the founding father of vaccination. Nonetheless, his discovery would prove to be a profound turning point; the beginning of a centuries-long endeavour to save millions of people from smallpox and other diseases. The success of vaccination gave rise to the idea that certain diseases could not only be controlled but wiped out entirely, as the eradication of smallpox, in 1979, would eventually prove.

The success of the smallpox campaign inspired legions of doctors, scientists and health workers to believe that disease eradication was possible. However, thirty-seven years later, smallpox remains the only disease to be successfully eradicated. It has taken decades to bring the world tantalizingly close to the eradication of another fearsome disease: polio, which once killed, crippled and ruined the lives of millions and struck terror into the hearts of families around the world. If polio is finally wiped out, the eradication of other well-known diseases, such as measles, could be within reach. Even the eradication of malaria is on the table.

The words polio eradication sound clinical and medical, perhaps even underwhelming and technical. The truth, however, is costly, messy and sometimes heartbreaking. Success would be a staggering victory; polio eradication could inspire and embolden scientists to make other, even more momentous, breakthroughs, making medicine as inspiring for the twenty-first century as the moon landings were for the twentieth.

A world without just one or two of its terrifying epidemic diseases would be radically different to the one we live in. First world countries could save billions of dollars in health spending and foreign aid, while developing nations could see a boom in their productivity and economic output. Our already-bulging planet could have many more human beings to feed, house and employ. The balance of global power would alter in ways we cannot yet envisage.

These arguments are not new and nor is the human effort to eradicate disease. This book explores the complicated history of vaccination and our efforts to tackle some of the diseases we have most feared. It tells the story through one disease, polio, and describes first-hand the final stages of one of the biggest health campaigns in history, as well as the stories of those who risk their lives to achieve what can seem an impossible aim.

Giving all children the polio vaccine has required creative solutions and massive collaboration. To reach remote communities, the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) has delivered vaccine to some of the most inaccessible parts of the world, using helicopters, motorbikes, boats and camels. The scale of the task is mind-blowing: when polio still naturally occurred throughout India, each round of national immunizations involved 640,000 vaccination booths, 2.3 million vaccinators, 200 million doses of vaccine, 6.3 million ice packs, visits to 191 million homes, and the immunization of 172 million children. Innovations developed in India included house-to-house vaccine delivery plans and finger-marking. Messages were painted on the chimneys of brick kilns to encourage migrant workers to vaccinate their children; mobile health teams vaccinated nomadic populations; vaccination posts were established at borders and transit points, and in bus and railway stations; strategies that were used again on the Afghan-Pakistan border and in the Horn of Africa.

The polio eradication programme has worked in times of peace and war, developing strategies to vaccinate children during conflicts and humanitarian emergencies and establishing Days of Tranquillity to interrupt conflicts in the Americas and later in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Afghanistan. In 2013, vaccine manufacturers delivered an astonishing 1.7 billion doses of the oral polio vaccine (OPV). Experts estimate the cost of the final push towards eradication between now and 2019 will be $7 billion.

Yet although polio has now been beaten back and is endemic in only three countries in the world, eradication is far from certain. Immense logistical difficulties, political intrigue, war and cultural and religious beliefs form immense obstacles to disease eradication; in the case of polio, this final goal has been set back decades.

The history of disease eradication campaigns demonstrates that the final stages are by far the hardest. An almost Herculean effort of will is required to maintain the immense momentum and funding needed to be channelled towards a tiny number of cases. The history of disease eradication in the twentieth century is largely the story of falling at the final hurdle. After billions of dollars, decades of work and the deaths of hundreds of health workers deliberately targeted for their work in saving children from disability and death the future of a world without epidemic diseases might come down to a team of polio workers determined to deliver the final few drops.

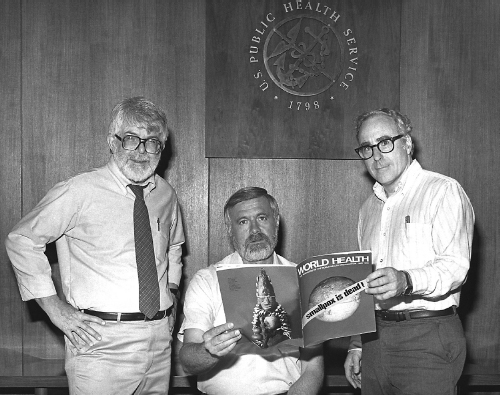

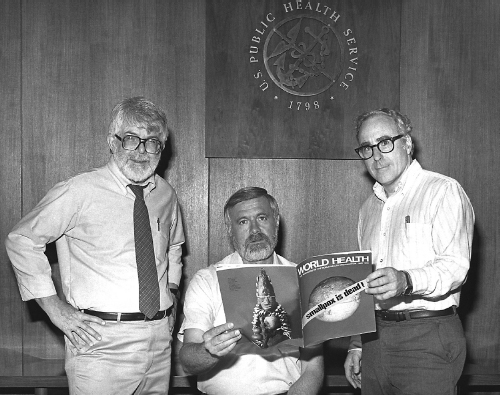

The medical missionary Bill Foege (centre) was crucial in developing the surveillance and containment strategy that played a key part in ending smallpox. Here, he celebrated the eradication of the disease in 1980, with two other former directors of the programme at CDC in Atlanta, Dr J. Donald Millar (left) and Dr J. Michael Lane (right).

1

THE HIPPIES WHO BEAT SMALLPOX

Smallpox eradication really is one of the greatest accomplishments in health in the twentieth century and those of us who have come after live with the most important legacy of smallpox eradication, which is infinite benefits from there being no more smallpox. All the people that would have got smallpox and would have suffered and all of the resources that would have been spent on managing smallpox, are now saved. So the great benefit of eradication is absolute prevention. It guarantees that youve got that stream of benefits, in perpetuity, into the future.

Next page