Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Angela Lindsay Kingue, and her mom

Suffering produces endurance, and endurance produces character, and character produces hope, and hope does not disappoint us.

Romans 5: 34

One of Franklin Roosevelts favorite poems was Kiplings If, which presents life as a continuous test. Roosevelt too had passed through endless tests of endurance, of waiting, of repeated disappointment, of triumph and disaster, certainly since summer 1921 when he was stricken by polio. He came to feel truly at ease only among the worlds castoffs, as his wife, Eleanor, observed.

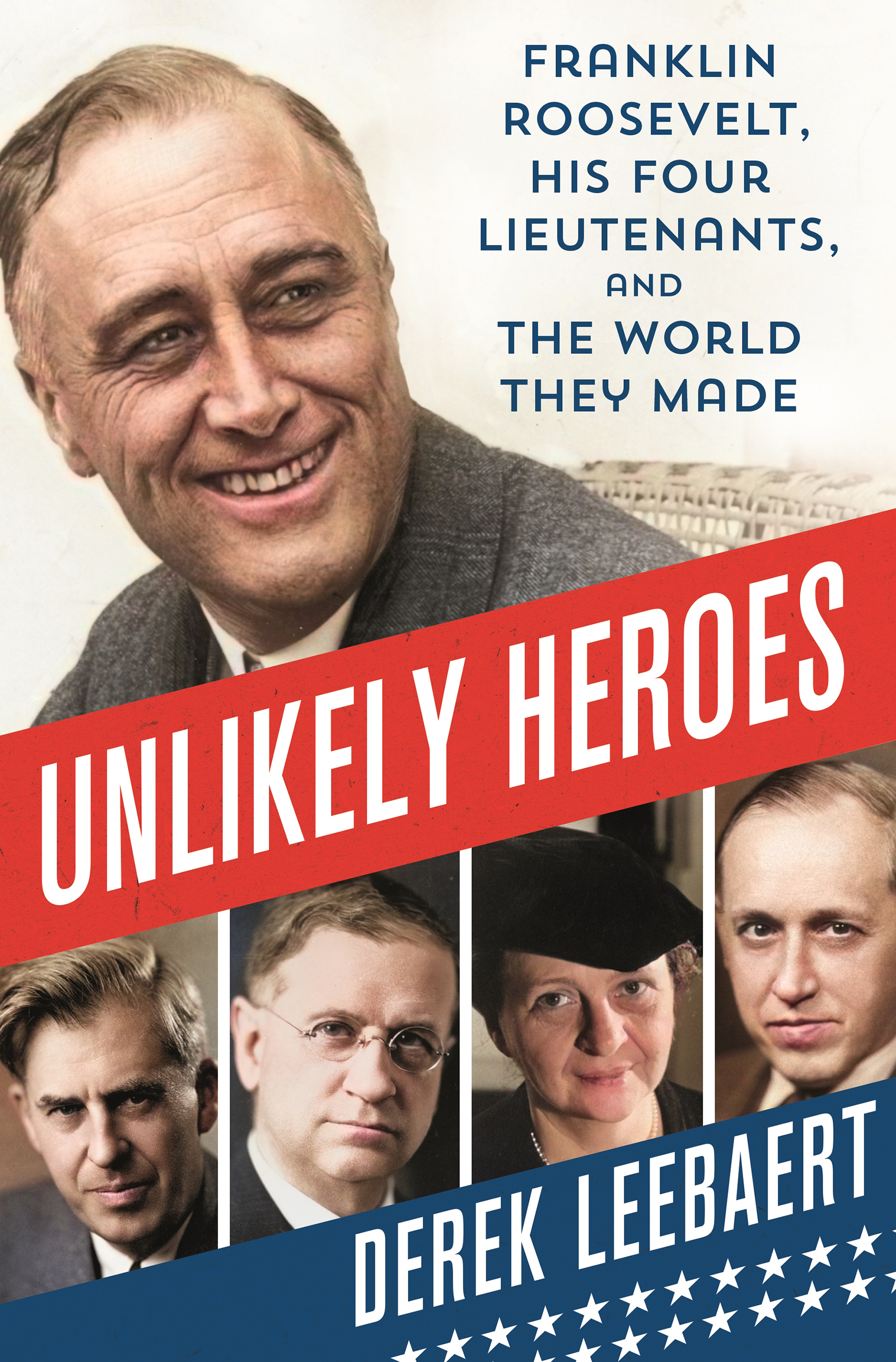

Only four people served at the top echelon of Roosevelts presidency from the frightening early months of spring 1933 until he died in April 1945 and, in their different ways, they were as wounded as he. This was no coincidence.

Himself crippled, Roosevelt had overridden the prejudices of that era toward those who were thought to be damaged. These three menand, unprecedentedly, one womanwere peculiar outsiders rather than actual castoffs. He could sense their despairs even as they built the great institutions being raised against the Depression, implemented most of the projects and reforms known as the New Deal that remade their country, and proved themselves vital to victory in World War II.

They were his key lieutenantsthe tough, constructive, enduring core of his government. In an era when unmatched concentrations of power gathered in Washington, they rammed their priorities throughFDR willing, of course.

Up to 1933, none of these four would ever have been considered for high office. Yet each riveted the nation during the celebrity-crazed 1930s and towered as world figures when, a long twelve years later, the adventure ran down. They called one another friends, if often through gritted teeth, and were bracketed together by the press and by their swarms of enemies. Their suffering intensified the relationships among themselves, and with their president. Like Roosevelt, each had much to hide, and all lived on the edge of calamity, as did their country.

The best way to come to terms with Franklin Roosevelt, I believe, as well as to penetrate the maze of his presidency, is to take the synoptic view that arises from examining their lives. To this end, my book sheds new light on Roosevelt and on his dangerous times, and now is the moment to do so. The 2020s raise uncomfortable parallels with those most world-changing of years during the last century: social upheavals, climate extremes (the Dust Bowl), an urge to rebuild, and furious politics (the cry of America First in both epochs), while world disorder threateningly increases.

Harry Lloyd Hopkins, son of an itinerant harness maker from Iowa, was forty-one when Roosevelt took office. He lends himself to fiction, as do all the others, but only Hopkins has figured in a novelthe Pulitzer-winning dramatist Jerome Weidmans Before You Go (1960)as the thinly fictionalized Benjamin Franklin Ivey, the sickly, self-promoting assistant director of a settlement house who ascends ruthlessly from the Lower East Side to the peaks of decision-making in Washington. Such had been Hopkinss path in real life as he leapt from running boys baseball games to being called the nations largest employer as the New Deal fought overwhelming joblessnessand, even more surprisingly, to then becoming the presidents Number 1 adviser.

Yet Hopkinss self-destructive habits tore through his life; he also suffered from ulcers and the complications of a major cancer operation. Much of his death-defying agony could have been avoided. Nevertheless, his illness cast him as a grievously wounded hero who refused to leave the field. This became a source of power, and it drew him closer to FDR.

Harold Ickes, fifty-nine at the start, was the abused son of an alcoholic father. He had worked his way through law school to become a peoples counsel in Chicago for causes such as the newly founded American Civil Liberties Union and the citys Indian Rights Association, which he organized. He had sought to be a kingmaker in progressive Republican politics, and failed humiliatingly. A long, wretched marriage to a rich divorce only turned worse after he seduced his stepdaughter. By 1932 he was describing himself as a loser, continuously self-medicating a torturous insomnia and constant headaches with Nembutal and whiskey, his moods swinging between rage and unrestrained joy. Some days he literally could not speak. A white-shoe Wall Street lawyer he had never been. Roosevelt appointed him from nowhere to be secretary of the interior. This position merely became his base as he accumulated so many responsibilitiesnot least, as the countrys unrivaled builder of public works, its Secretary of Negro Affairs, its energy czar, and czar as well of all U.S. territories, such as Alaskathat he functioned basically as the chancellor of an ever-watchful monarch. He was the first U.S. official to be denounced by Hitler, in 1939, and he itched for war. Once it erupted, he proved a formidable war administrator, and central to Allied victory.

Frances Perkins, fifty-two, had known Franklin Roosevelt in the days when, she remembered, he could vault casually over a chair, like a beautiful, strong, vigorous, Greek god king of an athlete. She reinvented herself as a Boston Brahmin, dedicating herself to God, to workers rights, and to putting an end to the horrors of child labor. She brought Hopkins into Roosevelts orbit and, in Washington, served as FDRs far-ranging secretary of labor. She was an essential force behind Social Security, minimum wage laws, unemployment insurance, and the rights of workers to organize. Less known are the terrible mistakes from which she saved the Administration and, because she also headed the Immigration Service, how hard she fought on behalf of refugees. As hostilities loomed, it was she who provided FDR with the sharpest assessments of the crumbling European balance. Then, often working closely with Ickes, she became pivotal to the war effort.

Her husband, Paul Caldwell Wilson, was a cameo version of Franklin Roosevelt: handsome, upper-class Episcopalian, Dartmouth, delightful in manner, and a rising star in New York progressive politics. They had a daughter, and Perkins yearned for more children. However, Paul was gripped by manic depression, as bipolar disorder was known in his lifetime, and he squandered his inheritance. Finally she had to institutionalize him, at enormous expense to herself, at the Haven, in Westchester County. The time would come when her daughter also had to be hospitalized, and the money drained away.

Perkins was ever moved by a deep sadness. Several times she tried to escape Washington for a proper place in life, as she told FDR, who would not hear of it, and she suffered pain even from seeing her picture in the news. Ultimately, her sacrifice left its enduring marks, including commemoration by the feast day of Frances Perkins, Public Servant and Prophetic Witness, in the calendar of the Episcopal Church.

Henry Wallace, a crisp forty-five, was driven by an intellect