IMAGES

of Rail

OREGON &

NORTHWESTERN

RAILROAD

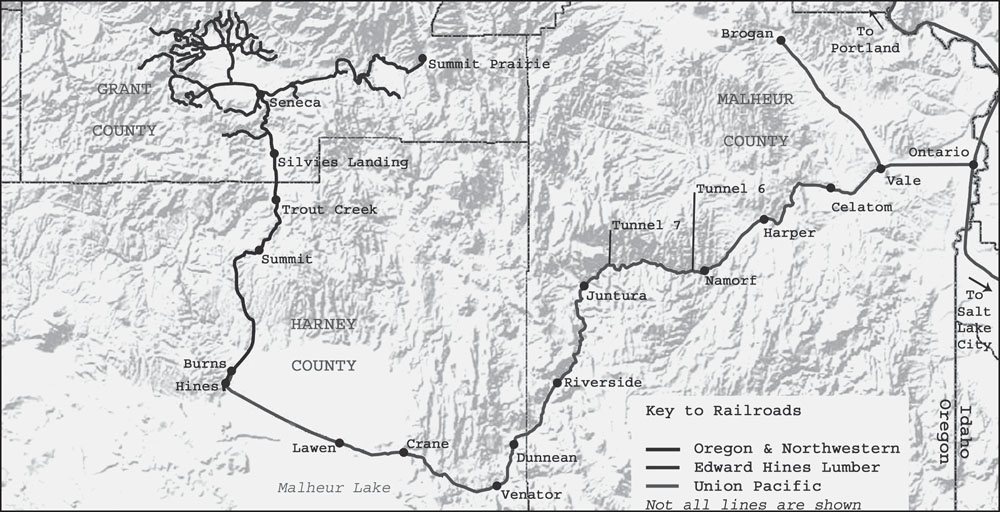

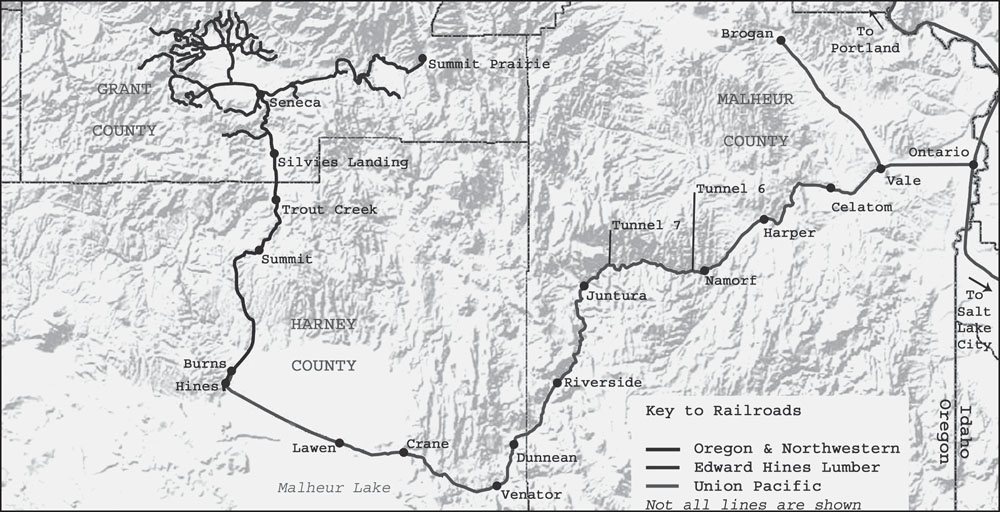

This map shows routes of the Oregon & Northwestern (O&NW) and associated railroads. (Jeff Moore map.)

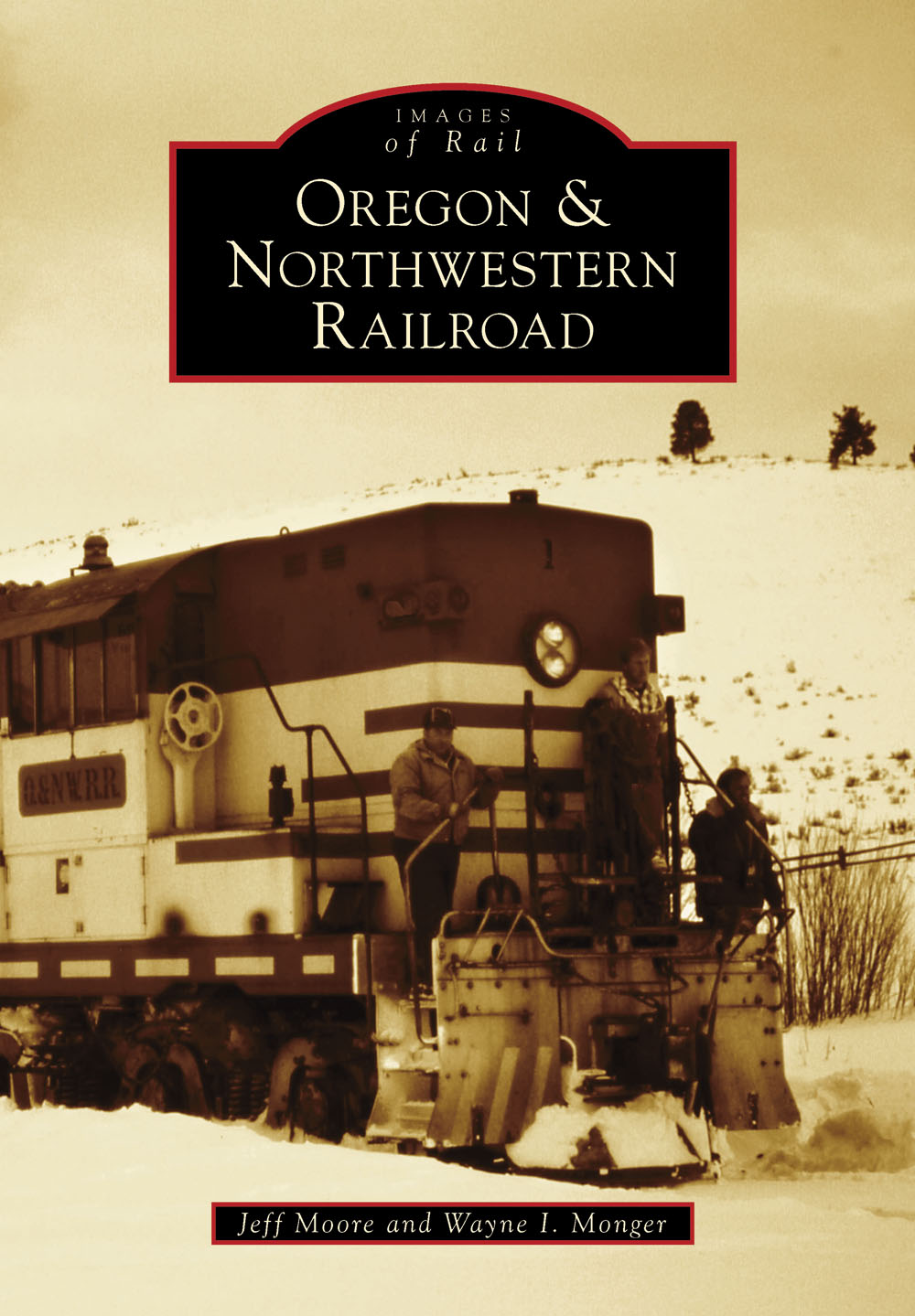

ON THE COVER: An Oregon & Northwestern train crew has gathered on the front walkway of the No. 1 during switching moves at Seneca. The date is February 23, 1984, and the O&NW will be history in less than three weeks. (Wayne I. Monger photograph.)

IMAGES

of Rail

OREGON &

NORTHWESTERN

RAILROAD

Jeff Moore and Wayne I. Monger

Copyright 2013 by Jeff Moore and Wayne I. Monger

ISBN 978-1-4671-3047-9

Ebook ISBN 9781439644249

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013933773

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

Dedicated to the memory of railroading in Harney and Grant Counties.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Oregon & Northwestern and associated railroads operated in one of the most remote locations in the continental United States. The authors are indebted to many who helped us along the way in compiling this story, and without whose help this book would not have been possible.

First off, a special thank-you needs to go to the Harney County Historical Museum, with special recognition to Janice Cupernall. Janice has been invaluable in helping us access the files and photographic collection the society preserves.

Second, recognition must also go to those who have opened their own photography work and/or image collections to us, or who have otherwise helped us along with stories and/or other information. These include Ivor J. Monger, Vic Neves, Charles Heimerdinger Jr., Jerry Lamper, John Cummings, Jimmy Bryant, Lee Hower, Martin Gabrielle Morisette, the late Ken Meeker, the late John Henderson, John Taubeneck, Tom Moungovan, Brian Winchester, and Dick Dorn. A big thank you must also go to Glen Comstock and Philip Schnell for their ongoing efforts to scan and make available historical logging images, and to those organizations and individuals who have contributed their work to this project. Finally, a thank-you goes as well to Paul Taylor and Loren Canaday, both Harney County railroaders.

Third, a big thank-you needs to go to Jared Nelson and Arcadia Publishing for their willingness and interest to take on this story.

Lastly, both authors wish to thank their families, Lynda Monger and Alicia and Kinyon Moore, for your love, support, and above all patience during the creative process.

INTRODUCTION

The Cascade mountain range casts a long and harsh rain shadow over the eastern two-thirds of the state of Oregon. The land east of the mountains is a raw one, consisting mostly of plateau basalt flows 25 million years to 10 million years old, thinly vegetated with shrubs and bunchgrasses specially adapted to live in poorly developed soils and dry conditions. Fertile soils capable of supporting agriculture are few and far between, located predominately in the beds of prehistoric lakes and along the few perennial streams and rivers draining the country.

Railroad builders found very little to attract their interest in this vast land. The scattered agricultural settlements individually needed the access to the outside world railroads provided, but none by themselves could produce enough revenue to justify the enormous costs of building railroad lines. The town of Burns, at the western edge of the Harney Basin, is one of the largest and most important of these settlements. By the 1870s, the burgeoning town became the focal point for freight and stage roads connecting the region with the outside world.

Various promoters and companies projected railroads through eastern Oregon, but the residents had their hopes dashed as every railroad projected to pass through or near Burns failed far short of the community. The most serious attempt arrived with the dawn of the 20th century, after railroad financier Edward Henry Harriman gained control of the Southern Pacific (SP) and Union Pacific (UP) railroads. Harriman sought to gain efficiencies by welding the two railroads into one, and as part of these efforts he envisioned a new main line running from the Willamette Valley eastward across the Cascades and the high desert that would provide a direct route to expedite east-west traffic to and from Oregon over the combined system. In late 1905, construction forces of UP subsidiaries Malheur Valley Railway and Vale & Malheur Valley Railway commenced building a new line running west from Ontario, Oregon, reaching the community of Vale by January 1907. UP construction crews returned in 1910 to extend the Malheur Valley from Vale northwest to Brogan and again in 1912 to start pushing a new line built under the joint auspices of the Oregon Eastern Railway and the Oregon-Washington Railroad & Navigation Company from Vale west into the rugged Malheur River canyon. However, Harrimans death in September 1909, followed by successful efforts by the United States Justice Department to undo the UP-SP merger under the Sherman Antitrust Act, effectively killed any chances the railroad might be completed. Despite this, the UP tracklayers continued pushing the line westward and in December 1916 emerged into the eastern fringe of the Harney Basin at the small town of Crane. Union Pacific realized that no increased traffic would be gained by any further construction, and Burns found itself 30 frustrating miles short of the railhead.

While Burns existed primarily on agriculture and ranching, the town did lie just south of one of the largest stands of ponderosa pine found anywhere in the world. The trees grew on the Blue and Ochoco mountain ranges above the 4,000-foot elevation level. Their remote location limited any early exploitation of the forests, and in 1906, President Roosevelt swept almost all of these forests into the forest reserves. The reserve status initially placed the forests off-limits to any commercial harvesting. However, by the early 1920s, the reserves had been reorganized into national forests, and attitudes within the US Forest Service, the federal agency charged with administering the forests, had shifted away from its original Progressive-era conservation goals to commercial timber production.

Into this scene stepped one Edward Barnes. Barnes first visited the Malheur National Forest around Bear Valley, 40 miles north of Burns, in 1919, and immediately became a tireless promoter of the region. Barnes started by securing harvesting rights to all the private timber he could, but quickly realized that any substantial commercial development would require access to the US Forest Service lands. Timber surveys estimated 6.725 billion board feet of government timber lay in the area tributary to Burns, plus an additional 210 million board feet in private ownership. Barnes found receptive ears to his plans within the Forest Service.

Over the next several years, Barnes orchestrated what would become one of the largest single timber sales the Forest Service ever offered. The sale in its final form included 890 million board feet of timber on 67,400 acres of government land centered around Bear Valley. Ponderosa pinetermed western yellow pine in the prospectusaccounted for most of the sale, at 770 million board feet. Other species included Douglas fir (78 million board feet), western larch (30 million board feet), white fir (10 million board feet), and lodgepole pine (2 million board feet). The Forest Service estimated that the Bear Valley sale, coupled with privately owned timber and the agencys intentions to make other government timber available in future sales, would allow for an annual sustained yield cut of 68 million board feet

Next page