Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress.

The Frozen Logger, words and music by James Stevens. TRO - (c) Copyright

1951 (Renewed) Folkways Music Publishers, Inc., New York, NY.

International copyright secured Made in USA

All Rights Reserved Including Public Performance for Profit

Used by permission

PART ONE

Outer Bark

The outer bark is the trees protection from the outside world. Continually renewed from within, it helps keep out moisture in the rain and prevents the tree from losing moisture when the air is dry. It insulates against cold and heat and wards off insect enemies.

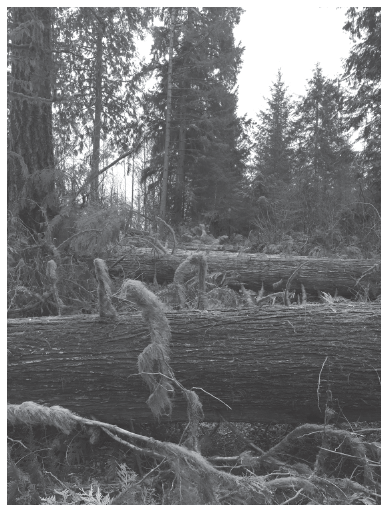

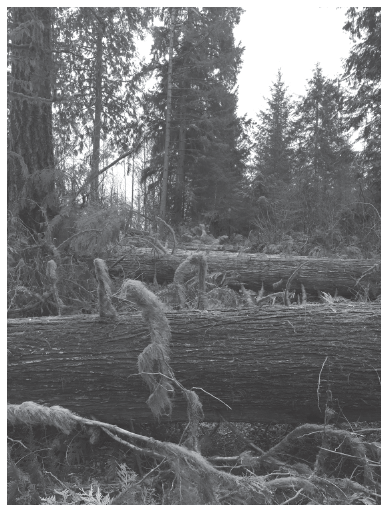

I sit on a recently felled Douglas fir and look around. It is early evening and our loggers are gone for the day. Floaty gnats inhabit the slanting light.

A sword fern frond reaches out and touches my notebook. Its other fronds merge with Oregon grape, salal, fir branches, cedar boughs, and chunks of bark. The soil is dark and soft and airy. I touch it. I make three dark stripes on each of my cheeks. The soil is drier than I expect; my stripes are smudges.

I want to roll around in the newly exposed dirt and hear what it has to say. It smells rich and full of secrets. Everything has been opened up. Stories await my hearing. This soil knows about the storms and floods and eruptions. It knows about the Cowlitz peoples, the Hudsons Bay Company trappers, the first White settlers. And does it hear my brothers voice in the ravens call? Does the land remember hislove? This forest was my growing ground from nine to eighteen, then a place to visit from Japan and the East Coast, and now home again. How can I better hear what it has to say to me?

From my seat on the log, I observe a large old snag in the middle of the cut. Weve left it as a perch for hawks and crows. The broken branches stand black against slow-moving clouds backlit by the setting sun. In this gloaming, I listen to the trees.

At the edge of the cut lies Gemini Grove, six acres of majestic hundred-year-old trees my sister-in-law Lou Jean and I have set aside. We go there for walks and contemplation, and the grove shelters critters that like deep shade. It is also home to my brother Steves Tree, where we go to remember him.

As the harvest enters the third week, Lou Jean and I walk the wetland trail in the grove. In the low spots, water stands at six inches. Last years alder leaves line the bottom, and new lovage nudges through the surface. A long strand of green-gray moss floats over my blue rubber work boots. Later I look up the moss. Common name: witchs hair lichen; Latin: Alectoria sarmentosa. Lou Jean likes to gather it and place it around the ceramic woodswoman that holds some of Steves ashes. She likes him to be warm.

We have hired a father and son team, Peter Sr. and Peter Jr., to do the logging on this land above the Cowlitz River in southwest Washington. From the trail we can hear the grind and thump of their machines and then can see them beyond our fifty-foot boundary. This logging has daylighted our trail, bringing sun into pockets of fern and old-growth stumps sunken in deep shade for decades. Peter Sr.s saw whines from across the clear-cut as we enter a darker section of the grove. A tree falls and shakes the ground.

Peter is hand-falling. Our trees are too big for the modern-day processors most of the industry uses. Im glad. This method is more personal, a more gracious relationship between faller and tree.

As Peter falls them, his son Peter Jr. walks down each tree with a chainsaw, cutting the branches close to the trunk. Next he climbs into a processor, a huge bright orange Doosan that cuts the tree into logs.With another Doosan machine, a loader, hell pick up the logs and place them on their truck.

Im curious about Doosan, a Korean company, and find its website:

We trace our history to 1896. Our first product was Bakgabun, a womens cosmetic.

Doosan is made up of two Korean words.

Doo means a unit of grain, while San means a mountain.

Together, they mean little grains that can build a mighty mountain,

suggesting that great things can be achieved

when even the tiniest forces join together in a unified effort.

Some of our Douglas fir goes to Korea to be used in temples. These logs must be longer than thirty-six feet and larger than thirty-two inches top diameter. I wish all our trees went to such treasured purposes.

Our cedar is milled at Reichert Shake and Fencing, a family-owned mill just a mile and a half from our forest. Other local mills process fir into two-by-fours, plywood, telephone poles, and other utilitarian products. Douglas fir logs with the fewest defects are exported to Japan for home building, while rougher logs we export to China, where some are used to construct concrete forms. At least the imprint of the knotty wood grain stays embedded in the concrete, an echo of forest life from across the Pacific. I begin to imagine traveling to Asia to see and touch our wood in its new home.

A sampling of defects used to grade exported Douglas fir:

AS: Age Stain

BT: Beaver Tail

CF: Cat Face

EK: Excessive Knots

F: Fluted or Flared Butt

FC: Freeze Crack

HC: Heart Check

OH: Off-Center Heart

PR: Pitch Ring

SB: Snow Break

SK: Spike Knot

SP: Spangle

WS: Wind Shake

Another defect, known as a school marm, is the fork in a treetop log. The current spec sheet for a Longview sawmill reads: Buck out school marms back to a single heart; no forked tops. As a former schoolteacher, I take offense at this even as I laugh.

We can sell the bucked-out school marms and other rough wood for pulp to make paper. We will keep leftover parts of the trees for firewood. Woodworking friends come to look at the burls, yew, and other hobby wood.

Logs that are too big are a problem. Any log over thirty-three inches diameter on the large end is deemed oversized, and mills pay about 30 percent less. This is painful! We like to grow big old trees and enjoy the forest as it changes through time. But in the last ten to fifteen years, most industrial timber companies have shortened the rotation of their tree harvests. Instead of harvesting at sixty or ninety years, most companies log at thirty-five to forty years of age. As a result, most sawmills have retooled and can handle only smaller logs. Shorter rotations meet quarterly profit goals but force small landowners like us to harvest earlier or face deductions on the scale sheet.

I discover that some oversized wood from Pacific Northwest forests is used for coffins in rural China. The invitation to the monthly meeting of the Lewis County Farm Forestry Association announces an upcoming talk by the owner of Millwood, a company in Olympia that ships logs for this purpose. I tell Dad we have to go. He gathers his thirty-year-old Society of American Foresters clipboard and puts on his city clothes. I check to make sure the T-shirt he wears under his button-down isnt frayed.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).