1992 by William Dietrich

Originally published in 1992 by Simon & Schuster; first University of Washington Press paperback edition published in 2010; new Preface and Afterword 2010 by William Dietrich

14 13 12 11 10 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS

P.O. Box 50096, Seattle, WA 98145 U.S.A.

www.washington.edu/uwpress

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Dietrich, William, 1951

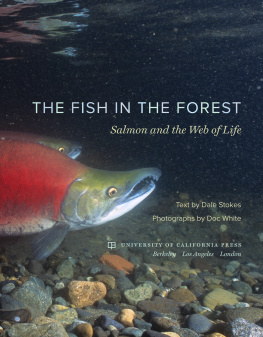

The final forest : big trees, forks, and the Pacific Northwest / William Dietrich. 2010 ed. / with a new preface and afterword.

p. cm.

"Originally published in 1992 by Simon & Schuster."

Includes index.

ISBN 978-0-295-99062-0 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Old growth forestsNorthwest, Pacific. 2. Old growth forest conservationNorthwest, Pacific. 3. LoggingNorthwest, Pacific. 4. LoggingNorthwest, Pacific. I. Title.

SD387.o43d52 1010 333.7509795dc22 2010031802

Printed in the United States of America

Designed by Ashley Saleeba

Composed in Adobe Caslon

The paper used in this publication is acid-free and 90 percent recycled from at least 50 percent post-consumer waste.

It meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

ISBN 978-0-295-80225-1 (electronic)

For my wife, Holly

Believe one who knows. You will find something greater in woods than in books.

Trees and stories will teach you that which you can never learn from masters.

ST. BERNARD OF CLAIRVAUX, 1145

Do you think I was born in the woods to be afraid of an owl?

JONATHAN SWIFT, 1738

PREFACE, 2010

Twilight Town

Life surprises.

Of all the possible outcomes for Forks, Washington, that I might have imagined in tumultuous 199091, when I first worked on The Final Forest, the unlikeliest would have been the Olympic Peninsula town's destiny as an international tourist destination. But in 2009, the Forks Chamber of Commerce recorded 70,000 visitors from all over the globe. The pilgrims were excited readers of Stephenie Meyer's Twilight series of four vampire novels set in the timber community, the first published in 2005. By late 2009 the books had reportedly sold 85 million copies worldwide, Forks was offering a Twilight Tour, and its tiny downtown boasted several stores selling Twilight memorabilia. One of these stores, Dazzled by Twilight (the book's heroine, Bella, is dazzled by vampire beau Edward), turned its interior into a spooky replica of the outdoors, with plastic grass on the floor, trees reaching to the ceiling to entwine, water spilling in an artificial stream, and a mural of the Olympic coast featuring werewolf Jacob. The store offers a mind-boggling array of merchandise, including Twilight dolls, lunch boxes, water bottles, T-shirts, magnets, bookmarks, sweatshirts, hats, jewelry, cosmetics, calendars, coffee, postcards, and cigarette lighters.

The store's owner is Twilight fan Annette Bruno-Root. She was a social worker in Vancouver, Washington, when she visited Forks, saw an opportunity, and created a small empire. I came to Forks and didn't see any evidence of Twilight, she said. It was empty storefronts. It was like going to Disneyland and finding Mickey and Minnie had been stricken from the cast. I wanted a place where someone like me could come. She took over the tour buses, opened three stores, and at this writing was planning a Twilight-themed restaurant and lounge in the former Vagabond, a mainstay eatery in the timber days.

By the time of Twilight's triumph, The Final Forest had sold about 36,000 copies. When Twilight sequel New Moon set first-day sales records, Meyer sold more books in twenty minutes than I'd sold of The Final Forest in almost twenty years. When I returned to Forks in 2009 and 2010, several people I met had never heard of my non-fiction depiction of their town. The Forks library had lost its only copy. The height of the timber war was not a happy time, and if many in Forks respected The Final Forest, they did not embrace it. Real people suffered real loss from environmental decisions that are bitterly remembered, and some found this book as painful to read as I at times found it to write.

Now, almost two decades later, I'm writing a preface for what has moved from journalism to history, but still timely history. We may never be finished arguing about forests, and the evolution of the debate is as fascinating as its origins. The final forest still has things to tell us about ourselves.

Sandwiched between the Twilight shops is the stump and sign proclaiming Forks as The Logging Capital of the World, but the claim is obsolete. A few logging trucks still rumble along Highway 101, but the majority of the city's employment today is tourism and government. Nearby Clallam Bay Prison opened in 1985, had doubled in size in 1992 when The Final Forest was published, and by 2010 employed about 440 people, half of whom live in or near Forks. Criminal justice and vampire romance are the new mainstays of the town.

When I first visited shop owner Jerry Leppell in September of 1990, he was selling 2,200 chainsaws a year. By the end of 2009, he was selling 70. Not only has the timber harvest declined, but harvesting methods have drastically changed to mechanical feller-bunchers operated from, still worked in the community, and his own profit margins are much thinner. The key is to live within your means, he said resignedly.

While Forks's timber identity has faded, the community takes great pride in its new literary fame. The daughter of Forks Chamber of Commerce director Marcia Bingham drew excited whispers from fellow teens when she wore her Forks high school sweatshirt through JFK airport in New York. She walked a little taller, Bingham recounted. Thanks to vampires, Forks had gone from a place few had heard of and fewer had visited to a town that seems familiar, in a literary way, to millions.

Forks High School is not just a place of vampires, of course. While it has not offered a vocational logging class for a generation, it plans to install Washington's first school boiler fueled by wood debris, an experiment in adapting the wood industry by finding new purposes, including renewable energy.

Forks has become a community that bridges two Americas. The Forks of 1990 is as Gone with the Wind as the antebellum South, replaced by a twenty-first-century Forks that is representative of a retail and information workforce in a nation obsessed with entertainment and escape. Just 16 percent of the male workforce was still working in the woods in 2009. The last great trees have been saved by the environmental old-growth campaign, but at the cost of a resource-based culture that was hard, dangerous, and communal. Forks has survived, but it has struggled with the rest of the nation in sustaining economic promise. Housing in Forks still is valued at only half the Washington State average, household median income is 20 percent below the average, and the percentage of residents with bachelor degrees or above10 percentis still less than a third that of Seattle. Like steel, autos, and my own newspaper industry, the shared pride in a trade has eroded, replaced by new technologies, new competitions, and new uncertainties.