The Stephen Bechtel Fund has established this imprint to promote understanding and conservation of our natural environment.

The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous contribution to this book provided by the Stephen Bechtel Fund.

THE FOREST AND THE FISH

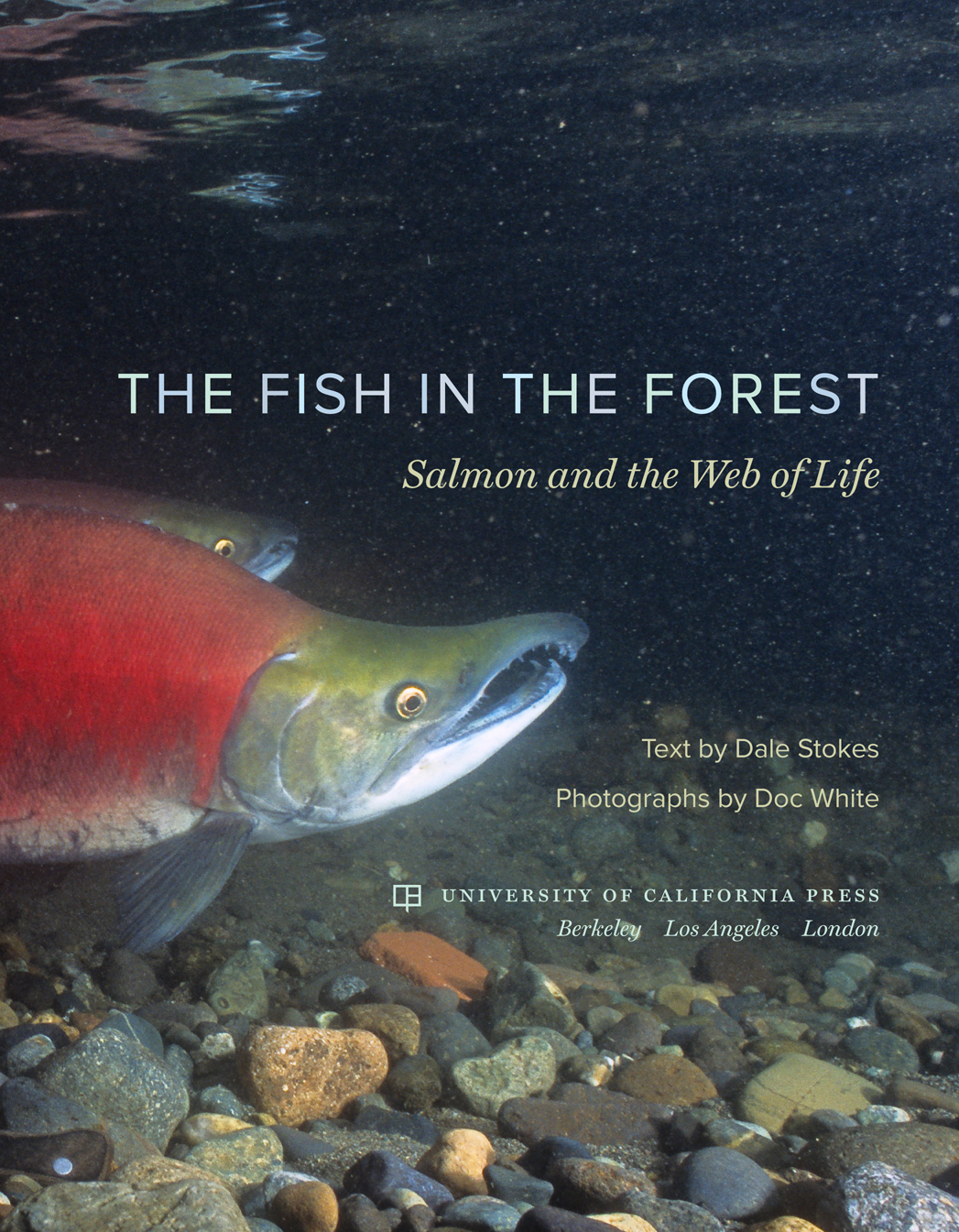

THIS STORY begins and ends with a fish. That is to say, it begins and ends with a salmon, a fish that so dominates its coastal marine and terrestrial environment that the entire landscape of the north Pacific coast of North America may be considered the Salmon Forest. This story begins and ends with a fish, but along the way the story of the Salmon Forest touches on all the life of the temperate rain forest: the trees and shrubs, the algae in the rivers and streams, the birds and bears and bugs, the bacteria in the soil, the whales, otters, and seals, and the other fishes that live offshore. It is the story of an extremely complex ecosystem. When the molecules of what was once a salmon find their way to the tops of trees and into the flesh of animals far removed from the ocean, rivers, and streams where the salmon once swam, and when the actions of the salmon themselves can be seen to shape the very landscape on scales that span hundreds of kilometers and thousands of years, it becomes very difficult to distinguish where the salmon begins or ends from the point where it transforms into something entirely different. So the story of the Salmon Forest is a story of the interconnectedness of the sea and land and a fish that has evolved and become entwined in a landscape, a story that serves as a metaphor for all of life on earth.

WHAT IS A FISH? Fishes are difficult to define conveniently because for nearly every potential defining characteristic there seems to be an exception. And this difficult-to-classify group of animals contains half the number of vertebrates on earth; nearly 30,000 species, in 445 families, living almost everywhere, from the tropics to the poles. An ichthyologist roughly defines a fish as an aquatic poikilothermic vertebrate possessing gills throughout its life and having fin -shaped limbs, if it has any at all. This gross definition includes all water-living (aquatic), back-boned (vertebrate) animals with a fluctuating internal body temperature (poikilothermic), specialized tissues that can extract oxygen from water and excrete carbon dioxide (gills), and paddle-like structures for moving through a fluid (fins). Hence the large number of fish that are fish.

The exceptions to this convenient piscine definition are spectacular examples of evolutionary adaptation. There are fish that spend the majority of their lives out of the water, with organs that have modified into primitive lungs; fish without fins at all, or fins that allow an ambulatory stroll as feet; and fish with fins that have transformed into a bewildering array of appendages like lures, claws, and spiky plumes. There are fish that lack bony skeletons, having only cartilage; and there are some fast-swimming pelagic species that maintain a body temperature that is warmer than the surrounding sea. Fish provide magnificent proof that given time and evolutionary natural selection, almost anything is possible. Adult fish range in size from less than a centimeter to more than fifteen meters in length. They can weigh anywhere from a few grams to dozens of tons. There are fish that make sounds, produce light in special organs, or secrete incredibly toxic venoms, and there are fish that can generate powerful jolts of electricity. Some fish can perform almost magical transformations in shape, color, or sex. They can live in the swiftest rivers, at the bottom of the ocean, under the polar ice, deep inside caves, or as parasites on others. And there are fish that can fly, or at least soar like birds.

So what then is a salmon? On the fourth day of his loving exposition on the sport and art of fishing, the piscator of Izaak Waltons Compleat Angler expounds nobly on the Atlantic salmon as the King of Fish, for reasons that go beyond the fact that the art of catching the salmon of the British Isles was a sport cherished by nobleman and peasant alike. Here was a creature that migrated yearly by the hundreds of thousands up from the ocean to the highest streams. The salmon performed staggering feats of endurance and strength, leaping obstacles in their path, during their tireless upstream quest to spawn. They were fickle and difficult to catch with a cast hook or fly, but fought strongly when they did bother to bite, and they were blessed, or cursed, with succulent orange-red flesh. Even four centuries ago, the close ties between the presence of the salmon and the nature of the surrounding British landscape, Waltons clear and sharp streams, were evident. Despite rules and regulations for the protection of the salmon, the decline in the quality of their habitat concomitant with the rise of industrialization led to a decline in their numbers. They were unable to adapt to a landscape increasingly and rapidly dominated by human society. Waltons streams, once choked with the bright, leaping, kingly fish, are now just a dream and a memory.

In the north Pacific, the salmon was, and still is, a central character in a coastal landscape that has been sustaining aboriginal peoples for thousands of years. The salmon, and hence, the Salmon Forest, provided wealth and security and was revered by widespread salmon-based cultures that ringed the north Pacific. In comparison, it is only relatively recently that the Salmon Forest has been subjected to the activities of commercial fishing empires and a competing, ever-growing complex of industries capitalizing on the wide range of natural resources present in the Pacific Northwests marine and terrestrial environment. And it has only been more recently still that we have had the tools and motivation to tease apart the complexities of the Salmon Forest ecosystem. The question remains whether or not we can learn from previous ecological mistakes and fruitfully apply this new knowledgewhich is ironically analogous to the mythology and wisdom of the salmon culture of North Americas First Nation peoplesand preserve not just the salmon but the forest as well.

WHEN WE ALLUDE to the Salmon Forest, we refer to a terrestrial landscape that covers an enormous coastal region stretching from California north through British Columbia and Alaska, encircling thousands of offshore islands, and extending across the Bering Sea and along the coast of Russia to Japan and Korea. This coastal zone includes all those watersheds in which Pacific salmon have swum and spawned. These rivers and streams can penetrate thousands of kilometers into the interior of the continents, and because, as we shall see, the influence of the salmon can extend far beyond the banks of a stream, the real Salmon Forest covers an area much larger than we might expect.

This region encompasses a staggering variety of climates, terrains, and ecological habitats. It includes the volcanic slopes of the Cascade Mountains and the mighty Rockies, as well as coastal wetlands, grassy plateaus, alpine deserts, and Arctic tundra. It contains thousands of bays, islands, and estuaries. Its watersheds include lakes, streams, and rivers large and small, from gushing torrents to tiny seasonal rivulets. The climate varies enormously over such a large area: the coast is temperate and moderated by the Pacific Ocean; it can be arid in the south or in the shadows of the mountains, or have staggering amounts of rainfall; it can be freezing cold in the Arctic and on mountain slopes; and it can experience seasonal snowfall or scorching dry heat. The incredible heterogeneity of the landscape is mirrored in the vast range of ecological communities that occupy it.

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS