Contents

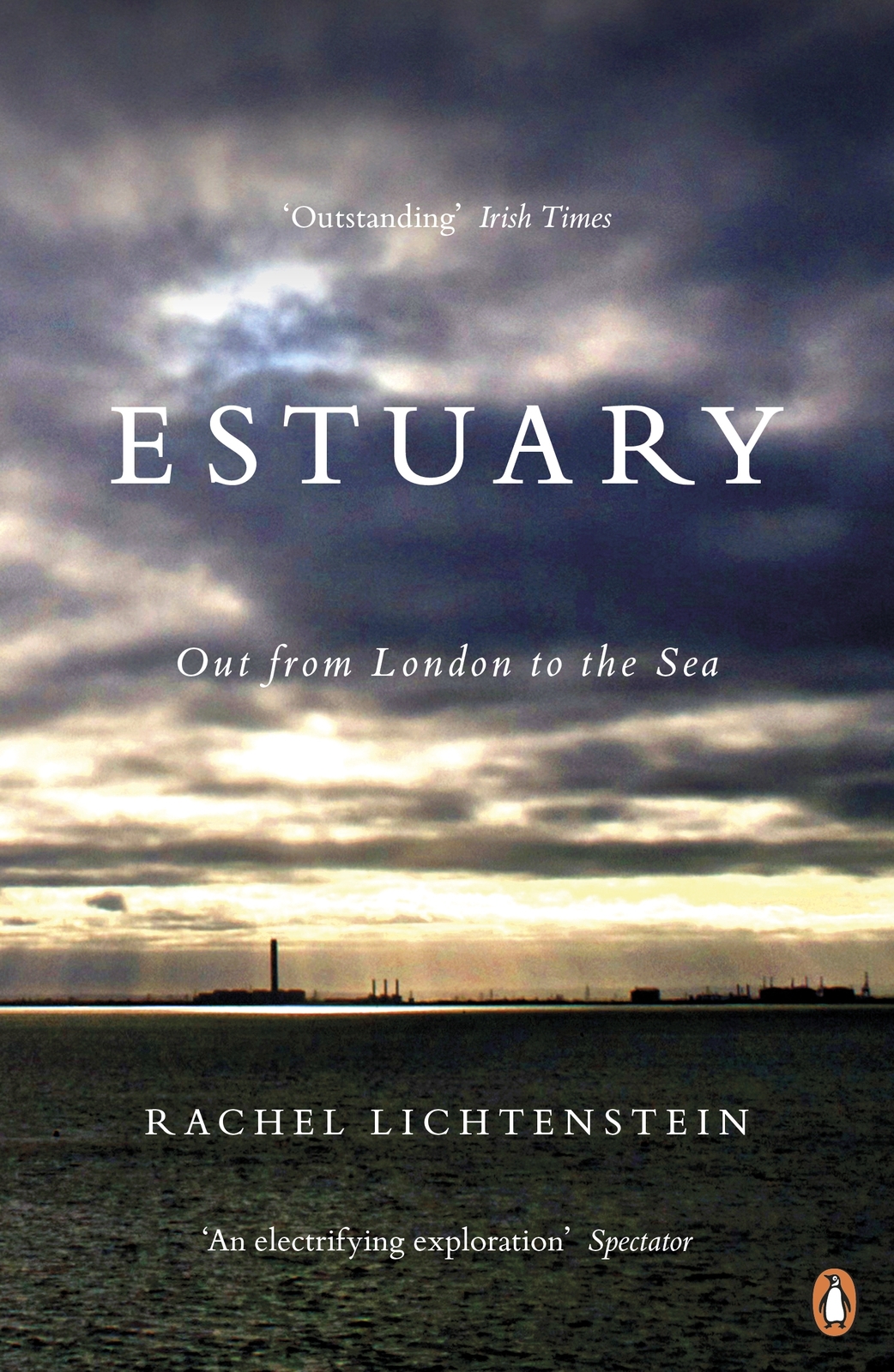

Rachel Lichtenstein

ESTUARY

Out from London to the Sea

HAMISH HAMILTON

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Hamish Hamilton is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published 2016

Copyright Rachel Lichtenstein, 2016

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Jacket Photography Simon Fowler

The photograph acknowledgements constitute an extension of this copyright page. Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher apologizes for any errors or omissions and would be grateful to be notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future editions of this book

ISBN: 978-0-141-91153-3

THE BEGINNING

Let the conversation begin

Follow the Penguin Twitter.com@penguinUKbooks

Keep up-to-date with all our stories YouTube.com/penguinbooks

Pin Penguin Books to your Pinterest

Like Penguin Books on Facebook.com/penguinbooks

Listen to Penguin at SoundCloud.com/penguin-books

Find out more about the author and

discover more stories like this at Penguin.co.uk

By the same author

Rodinskys Whitechapel

Rodinskys Room (with Iain Sinclair)

On Brick Lane

A Little Dust Whispered

Keeping Pace

Diamond Street

This book is dedicated to John Dickens (19452016)

The fishermen I came into contact with at Leigh were old men with no scholarship. They told me of their thoughts; the things they said within themselves as they sailed with the stars and with the wild waters about and beneath them. For sheer poetry I have never heard more beautiful things than fell from the lips of those unlettered men.

Nineteenth-century Methodist minister of Leigh

Introduction

On the night of the summer solstice 2011, I made my way to Hermitage Moorings, just east of Londons Tower Bridge. There were about a dozen vessels in the harbour when I arrived, tugs and Thames barges mainly, which had all been lovingly restored by a community of passionate enthusiasts. The historic boats made an impressive sight with the dark, wooden masts of the barges and their folded, heavy red sails silhouetted against the great royal palace behind.

I found Ideaal moored alongside an immaculately refurbished Thames sailing which now served as a permanent residence for a young couple and their dog. Skipping over the artfully arranged nets and ropes on the deck of the sailing boat, I hopped on to the fifty-ton Dutch barge. It had originally been built in the 1920s as a working barge to carry freight and has since been converted into a live/work studio by owner Ben Eastop although it remains a seaworthy vessel.

As the light slowly faded on the longest day of the year, I sat on deck with the rest of the crew, drinking bottled beers, sharing stories and watching the cityscape transform. By dusk, a low mist had begun to obscure most of the buildings. The iconic dome of St Pauls temporarily disappeared before re-emerging, floodlit, against the London skyline. Red-flashing beacons began to appear sporadically through the fog, marking the tops of tall cranes and skyscrapers. The skeletal frame of the Shard came suddenly into focus as every floor lit up simultaneously. At the same time, the beautiful Gothic structure of Tower Bridge behind us was illuminated from above and below, throwing a sparkling reflection into the black waters of the Lower Pool of London a place where so many of the worlds most important ships have anchored at different points in time. As night fell, the lights inside all the flats, hotels and offices along the riverside came on. We floated in the dark void of the river, suspended in time.

On the water, the sounds of the city seemed altered. I could hear the distant hum of traffic on the bridge, the clatter of trains rumbling past, the intermittent backdrop of sirens wailing, but it was as if these sounds were coming from another place altogether, not from the great, throbbing metropolis around me. I sat and watched the vast twin bascules of Tower Bridge being raised little by little. When they were fully open a Thames barge sailed silently past and drifted beneath the bridge before quickly disappearing into the shadows on the other side. On the remains of a wooden jetty nearby, I could just make out the shape of a large, black cormorant standing perfectly still, its huge wings outstretched.

The temperature dropped. The rest of the crew went below deck. I sat up top for a while longer, transfixed by the patterns in the dark water, before realizing we were moored somewhere near to where Irongate Stairs used to be the place where my Polish-Jewish grandparents would have disembarked nearly a century ago after a long, harrowing journey by sea. Their boat, packed full of Yiddish-speaking migrants, would have anchored offshore. Passengers would then have been transferred from the ship by rowing boat to the shore before making their way up the stairs and into the backstreets of Whitechapel and elsewhere to a new life. I remember the legendary East London Jewish playwright Bernard Kops telling me that, when his parents arrived from Eastern Europe by boat, they saw the open arms of the bridge as a mother welcoming [them] home.

There is another story about Jews and the river which haunts me whenever I am on the water. Further upriver, around London Bridge, is the site of a terrible legend from the time of the Plague. Back then, people hired to take them out of the City to avoid contagion. One time, a group of Jews was rowed out to a sandbank, where London Bridge was later to stand. The skipper demanded extra money to take them to the other side, which they did not have, so he left them there and they all drowned. The white water that swirls around this sandbank is said to be caused by these lost Jewish souls kicking up in torment.

By the time the night sky had grown completely dark, I had joined the others below in the former hold, which now served as the living quarters for the male members of the crew, with a small galley kitchen at one end and a large wooden table and chairs in the centre of the open-plan space. Ben asked us to gather around the table to examine a nautical chart of the Thames Estuary. We spent the next hour or so deliberating over the definition of the Thames Estuary; all we could agree on was that it encompasses the stretch of water between the River Thames and the North Sea. Defining its outer and inner limits seemed almost impossible; as we talked, the imaginary boundary lines shifted constantly throughout our discussion.