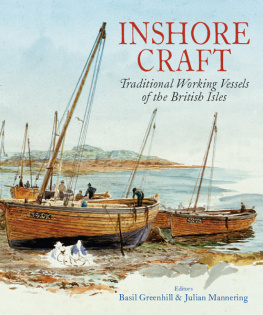

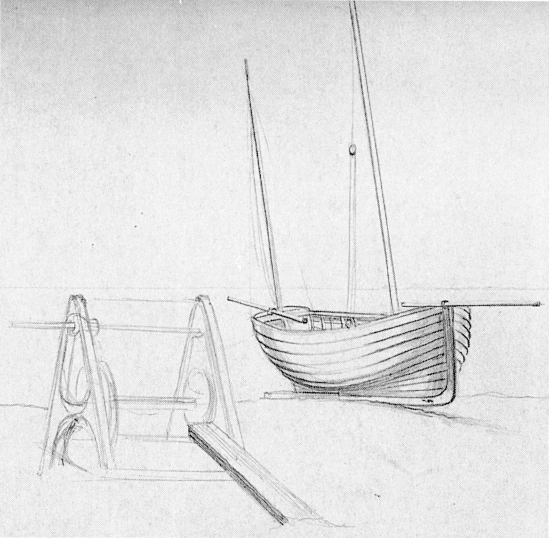

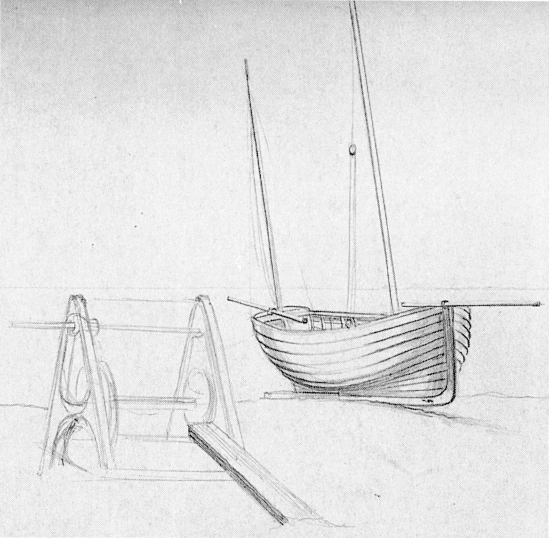

Deal sprat boat (NMM, Oke, neg no PAI7507)

Frontispiece: Scottish fishing craft off Great Yarmouth (NMM, neg no P75443)

Copyright Chatham Publishing 1997

This edition first published in Great Britain

2013 by Seaforth Publishing,

Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street,

Barnsley S70 2AS

First published under the title

The Chatham Directory of Inshore Craft in 1997

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library

PAPERBACK ISBN: 978-1-84832-167-0

HARDBACK ISBN: 978-1-84415-718-1

PDF ISBN: 978-1-47382-164-4

EPUB ISBN: 978-1-47382-260-3

PRC ISBN: 978-1-47382-212-2

All rights reserved. No part of this

publication may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means,

electronic or mechanical, including

photocopying, recording, or any information

storage and retrieval system, without prior

permission in writing of both the copyright

owner and the above publisher.

Typeset and designed by Tony Hart

Printed and bound in Singapore

Editor

JULIAN MANNERING

Consultant Editor

DR BASIL GREENHILL

Contributors

ALISON GRANT

North Devon salmon boat

DR BASIL GREENHILL

Boats and Boatmen and their Study

Barges of Devon and Cornwall,

Clovelly picarooner

Peggy of Castletown

MICHAEL MCCAUGHAN

Planked craft of Ireland

DAVID R MACGREGOR

Emsworth oyster dredger

ADRIAN OSLER

Craft of Scotland

TONY PAWLYN

Fishing craft of Devon and Cornwall

OWAIN ROBERTS

Craft of Wales

ROBERT SIMPER

Craft of the Thames Estuary and Wash, and the South Coast

MICHAEL STAMMERS

Craft of Northwest England

PETER STUCKEY

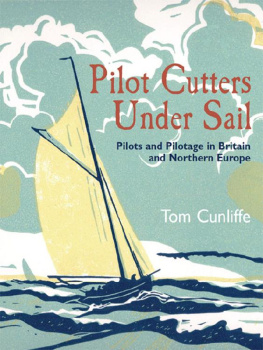

Bristol Channel pilot cutters

DESMOND TOAL

Irish curraghs

GLORIA WILSON

Craft of Northeast England

Contents

Introduction and Acknowledgments

A T THE beginning of this century our coasts and ports were the home of an extraordinary array of craft from Achill yawls to zulus, as diverse in form, function and name as the Parrett flatner and the Brixham mumble-bee: they are no longer. The traditional fishing boats have all but disappeared; the coastal craft which traded under sail have long ago been superseded by the lorry, the container and the motor ship; and the thousands among our population who gained a living from the sea, precarious as it was, have been succeeded by descendants most of whom work on land. We are no longer a maritime nation in the strictest sense, but an abiding interest in the lost world of traditional working craft remains and, indeed, is growing.

The intention of this book is to list, define and describe, and illustrate those distinct types which once fished and traded in home waters; its structure as a gazetteer is self evident. There have, of course, been a number of notable predecessors. Edgar J Marchs Inshore Craft of Britain in the Days of Sail and Oar and Eric McKees Working Boats of Britain particularly stand out but they are by no means inclusive of the huge range of types McKees work was not intended to be so, of course and while it would be presumptuous to pretend that this work is all-inclusive it is hoped that it contains the majority of identifiable types.

The criteria for inclusion were easy enough to establish though more difficult to apply; we have tried to include all those craft which were built for a particular task in a particular locality or region, during an era when fishing and trading under sail and oar were at their zenith. This is the period when the countrys population was growing fast with industrialisation and when there was an ever increasing need for food which fish went a long way to meet; and when that industrialisation, in tandem with the expansion of empire, led to a huge increase in coastal trade. This really is the period roughly 1820 to 1920. By the latter date the motor was changing the face of our coasts and country. So the English herring buss is excluded for being too early: the many coastal schooners, ketches and barquentines left out because they were not built for any particular locality though they were often easily recognisable as having come from a particular yard.

The initial inspiration for the book came from sifting through the wonderful collection of plans and photographs at the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich. In the 1930s The Society for Nautical Research had the foresight to commission the recording of our indigenous craft. Philip Oke travelled the country taking off lines of craft and models and measuring and reconstructing sail plans. Oliver Hill took hundreds of photographs of the same. Indeed, he continued to do so throughout his life and until as late as the 1960s. By this time a great number of the craft were in a poor state and many of the photographs in this book tell the story of sad decline. William Maxwell-Blake, a naval architect who amongst other activities involved himself with the design of small yachts, also recorded a number of vessels which he then drew up and described in Yachting Monthly, also in the 1930s. Many of the lines plans which have been included have appeared before in diverse publications, but not before at a scale at which so much of the detail can be assimilated. Many of the Oliver Hill photographs have not seen the light of day before, and certainly this is the first time that so many illustrations of all these craft have been assembled together. The accompanying texts are intended to introduce the types they are not definitive texts and point the reader to further sources. In that sense this is a first step book for those with a real enthusiasm who may be well acquainted even highly knowledgeable with one or more types but who want the broader picture in a single volume.

While we may mourn the passing of the age of sail and oar we can enjoy our present prosperity to look back on the men and the boats of a harder world and learn more about their skills and their tools. The accurate restoration of the few remaining craft, the building and sailing of authentic replicas, the development of maritime museums, and the increase of interest in local history will all further our knowledge. In Ireland, for instance, their regional craft are just now being researched by local enthusiasts with the backing of the French traditional boat magazine Chasse Mare. Though most of the vessels and the men who sailed them have now disappeared there is still much we can learn. We hope that this book will encourage and further promote the enthusiasm.

Acknowledgments

This book would not have been possible without the help of a large number of people whom the publishers would like to thank. First, Basil Greenhill and all the contributors applied themselves with an enthusiasm which knew no bounds and, on top of their textural responsibilities, helped with the sorting of the illustrations and filled many gaps from their own collections. The great majority of the illustration comes from the archives of the National Maritime Museum, particularly the Coastal Craft Collection and the Oliver Hill Collection, and thanks are due to a number of staff members there. Pieter van de Merwe quickly recognised the potential of the project and lent encouragement during the early stages. David Hodge was unfailingly helpful with the picture research and pointed me to many corners of the Museums collection which were, indeed, dark in their obscurity. Chris Gray, Head of Picture Research, ensured that all the material we needed could be made available and David Taylor lent every assistance to ensure that the illustrations were processed when they were needed.

Next page