For Bernard and Michle Cadoret

The publishers acknowledge the generous support of Ian Laing

Copyright Tom Cunliffe 2013

First published in Great Britain in 2013 by

Seaforth Publishing,

Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street,

Barnsley s70 2as

www.seaforthpublishing.com

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 84832 154 0

eISBN 9781473826335

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing of both the copyright owner and the above publisher.

The right of Author to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Drawings in Chapter 13 Pilot Cutter Seamanship by Martyn Mackrill

Typeset and designed by Roger Daniels

Printed and bound in China through Printworks International Ltd

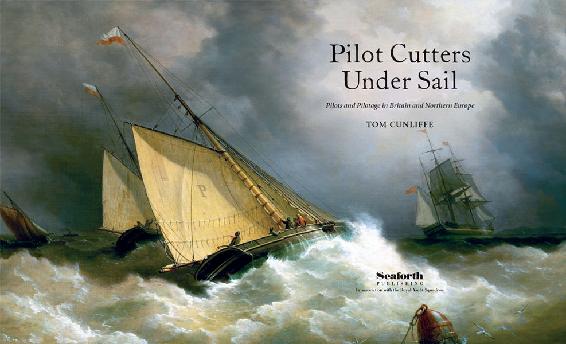

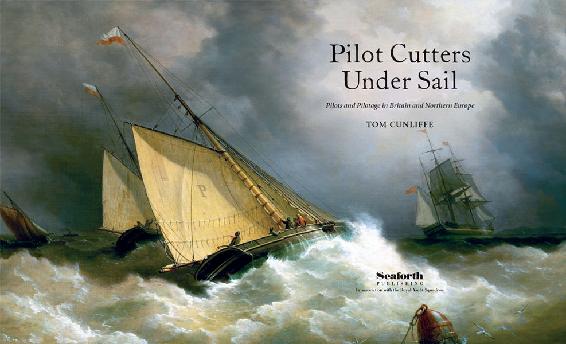

Competition in the early days

In this dramatic work by Admiral Richard Brydges Beechey entitled First Come, First Served and painted in 1883, three pilot cutters are racing hell-for-leather to board an Indiaman which has hove to in heavy weather to await the winner. The scene is somewhat stylised, but it encapsulates the spirit of this book.

( National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, UK)

Contents

Preface

I N THE LATE 1990s I was engaged by the French journal Le Chasse-Mare to produce a work on sailing pilots and their vessels. The book rapidly spiralled in scope and in 2001 two definitive volumes were published. These covered schooners in Europe and North America, as well as such diverse sideshows as the mighty pilot brigs of the Hooghly in Imperial India and the open-boat hobblers of Dublin Bay. A third volume was planned which would include the famous cutters of northern Europe but, as a result of restructuring in the publishing house, it was never written. Wishing in my heart to see this important material on the bookshelves, not only for myself and all those seafaring people who love a pilot cutter, but also for Bernard and Michle Cadoret, without whose initiative and tireless creative work inside and outside the magazine office the project would never have begun, I sought another publisher. Over a decade later, backed by my shipmate Ian Laing of the Royal Yacht Squadron, I made contact with Julian Mannering of Seaforth Publishing who had been involved as a co-publisher with the original books. He proved an enthusiastic supporter and so, at last, Pilot Cutters Under Sail sees the light of a new dawn.

Whilst the book is based on solid research by myself, my wife Ros and others, the flavour derives from the years I have spent at sea in pilot cutters. As far back as the mid 1970s, Ros and I sailed from England to Brazil aboard a 13-ton Colin Archer called Saari, said to have been built for a pilot in the Gulf of Bothnia in 1920. Homeward bound we took the long route via the Caribbean, the US and the Grand Banks of Newfoundland. The extreme weather we experienced in the late-season North Atlantic convinced us that, for serious seafaring, these boats had few equals.

Saaris engine rarely functioned so we sailed largely without auxiliary power, learning the hard way how to handle a gaff cutter in fair weather and foul, in tight confines and hove to out on the broad ocean. Saari was followed in the 1980s by the 35-ton 1911 Barry pilot cutter, Hirta. Unrestored and unsullied by yachtsmen who imagined they knew better than the pilots, Hirta was a glory. Complete with original mast, boom and cockpit, she came to us so untouched that she was still without electric navigation lights. Like Saari before her, she spread a big mainsail of flax canvas. With her, we sailed to Greenland, America, Scandinavia and Soviet Russia. She made many memorable passages, including the long beat to Newfoundland from Iceland, a four-day run to the West Solent from Norway and a traverse from North Carolina to the West Indies during which she weathered Hurricane Klaus, hove to in shocking seas on the edge of the Gulf Stream.As if this did not distinguish her enough, she also relished being short-tacked up the narrow, mooring-studded Beaulieu River sailed by a man, a woman and a teenage girl. She was an extraordinary sailing boat with the best manners I have ever experienced.

Hirta

Bristol Channel pilot cutter Hirta in mid Atlantic, 1983.

(Martyn Mackrill)

Following Hirta was a tough call, but the brand-new, wood-epoxy Westernman did us proud. Designed by Nigel Irens and built to our commission in North America, this 20-tonner, whose lines were inspired by the pilots of the Bristol Channel, ranted home across the North Atlantic in a highly respectable time, then carried on the good work by sailing to Arctic Norway, the heat of North Africa, and many a port in between. In all, we owned and cruised these cutters for over thirty years. Those decades formed us as individuals. Pilot cutters have a proud and charismatic history. They stir the souls of all who sail them, and attract the respect of people of the sea who have yet to do so. For me, this book represents something of a personal pilgrimage. Being given the opportunity to write it has been a privilege.

TOM CUNLIPPE, 2013

INTRODUCTION

Pilots, Cutters and Administration

P ILOT BOATS have always been found wherever ships seek a safe haven. Europe has been no exception and many were the ports whose cutters did grand work. Readers from Scotland and Finland, to name but two countries, may scan the chapter list of this book in vain for coverage of their cutters, but space and time cannot permit a totally comprehensive account. The doors had to close somewhere, so the ports and sea areas included were chosen on the basis of importance and the availability of material.

The pilot cutters which operated around northern Europe under sail until the time of World War I possessed a magic equalled by few other working craft. Built with performance in mind by and for men who knew what a boat was supposed to look like, they had to match speed with seaworthiness in all weathers. The position was clear. If they failed to board their pilot, they made no money, so any that ran for home as soon as it came on to blow saw their owners rapidly going on the parish. While some of the more prosaic pilot vessels were owned by corporations or cruised under other non-competitive circumstances, most vied one with another for the best jobs, and all had an overwhelming advantage over fishing and cargo vessels: in addition to a small crew, their only payload was one man or, at most, a few colleagues. So modest a burden meant that, like yachts, they would always sail to the same waterline. This gave builders a free hand to create the best possible forms, unhindered by the demand to perform adequately, whether drawing five feet of water or eight.