Contents

THE SHADOW OF THE MINE

THE SHADOW

OF THE MINE

Coal and the End of Industrial Britain

Huw Beynon and Ray Hudson

First published by Verso 2021

Huw Beynon and Ray Hudson 2021

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-155-3

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-156-0 (UK EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-157-7 (US EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020948743

Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

Contents

Tables

Figures

Map 1. Coalfields in Britain

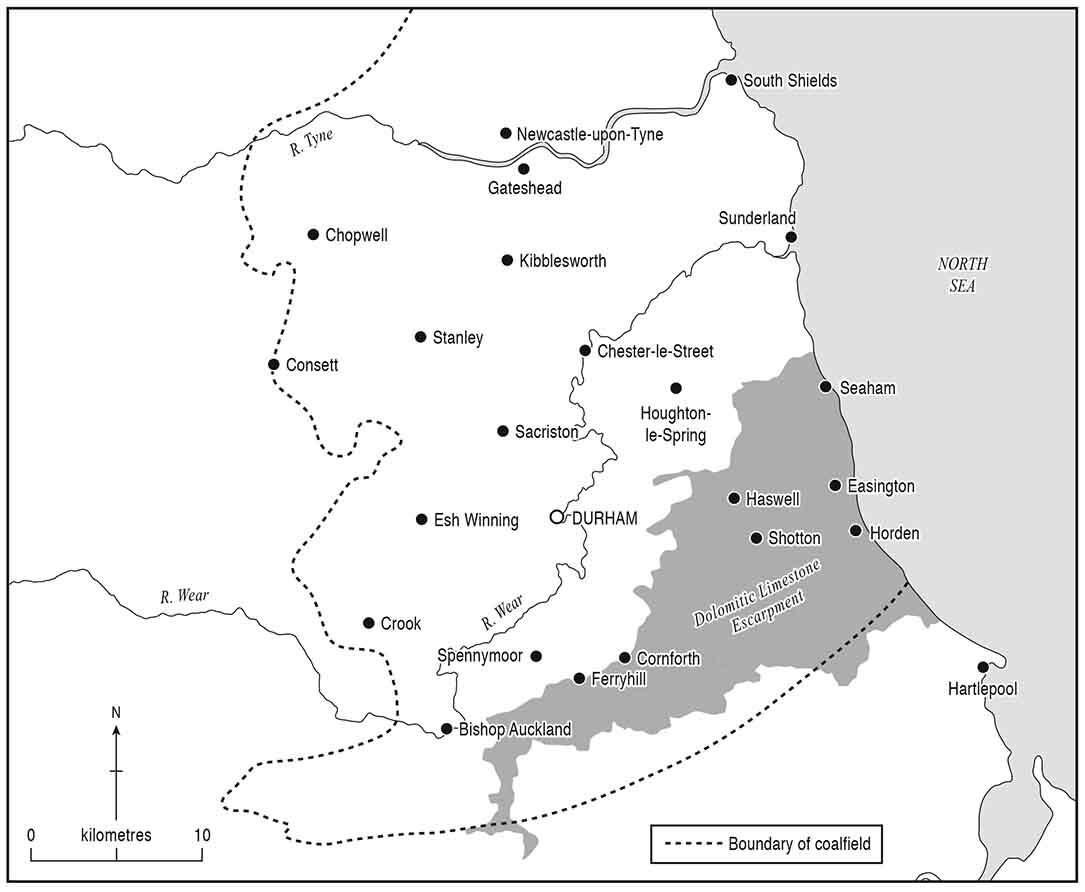

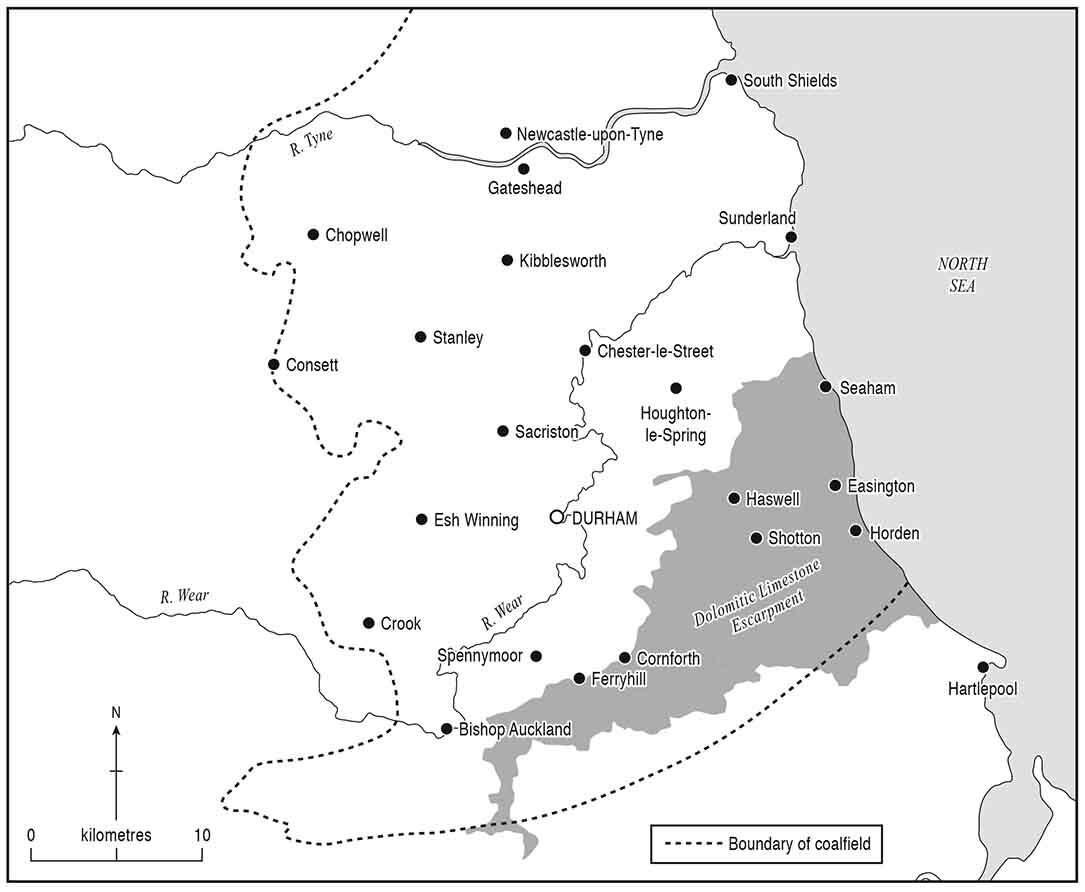

Map 2. Durham

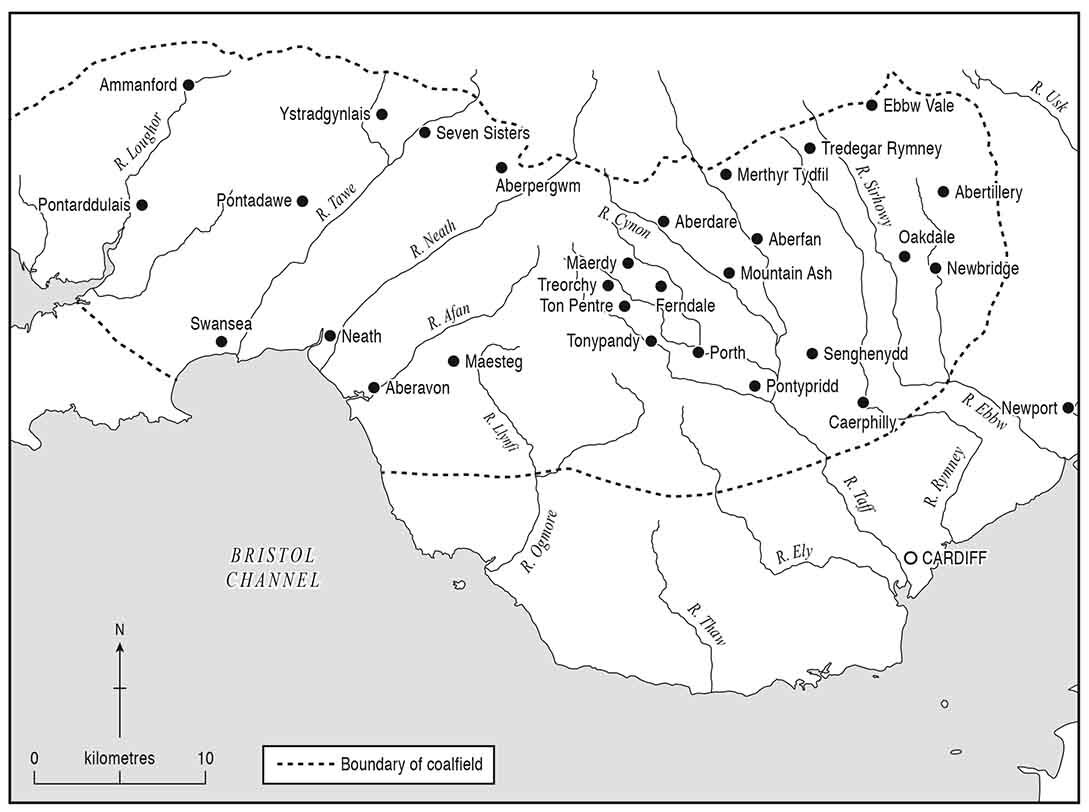

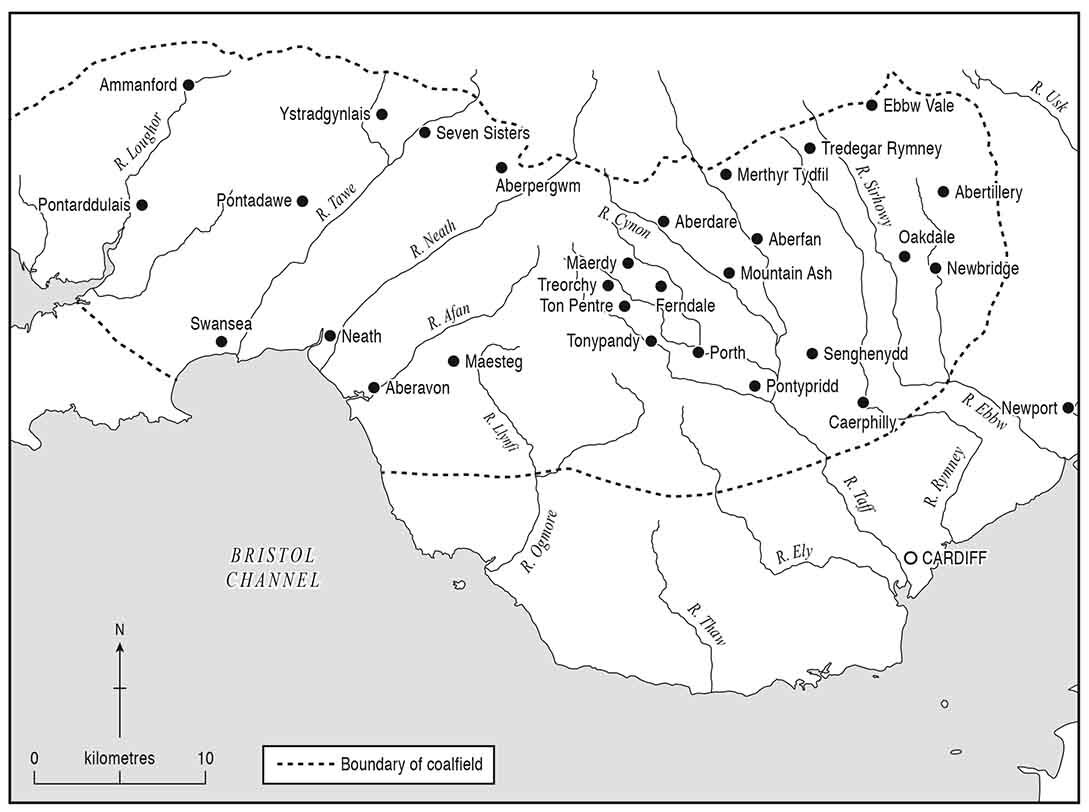

Map 3. South Wales

Every little boys ambition in my valley was to become a miner. There was the arrogant strut of the lords of the coalface who stand on street corners and look at the posh people that passed with hostile eyes; insulting them with cold looks because they were the kings of the underworld.

Richard Burton, The Dick Cavett Show , 1980

This is a book about the coalfields of Durham and South Wales, and the people who live there. We have come to know these areas well over the years, keeping up many contacts and friendships. This has brought home to us the need for a sympathetic historical account of how life has changed in these communities. Our aim is to explain why Britains coalfields, once significant centres of industrial production and political influence, became marginalised, and to explore the ways in which the state has played a central role in their declining fortunes.

These concerns were brought into sharp relief at the time of the 2016 Brexit referendum, when Durham and South Wales both voted strongly in favour of leaving the European Union. In the days and weeks that followed, the referendums outcome was greeted with incredulity, and often presented as the mutiny of the old and the uneducated a Peasants Revolt or an outburst of nostalgia for a time when Britain was Great. It seemed to us, on the other hand, that in the coalfields at least, the Leave vote was a case of a forgotten people striking back. Coalfield politics came back into the spotlight in the General Election of 2019, Brexit once more at issue, as large numbers of Labour seats in old industrial and mining areas, including in Durham, turned to Boris Johnsons Conservatives. It was a cataclysmic event, and one which suggested that historical working-class identities have been eroded.

In her 2016 investigation of surging support for the Tea Party Republican right among economically disadvantaged white voters in the USA, the sociologist Arlie Hochschild argued for the need to know others from the inside, to see reality through their eyes, to understand the links between life, feeling and politics, and to trace the deep story that sits behind the day-to-day anger and political rhetoric. At this time in Britain there is a similar need to trace the deep story of a disenfranchised working class, and to tell it through the voices of those whose communities have been taken apart piece by piece.

In attempting this, we have chosen the case of the coalminers. Before the First World War, Durham and South Wales were Britains leading coal-exporting regions, with a dominant position in the global trade. In South Wales there was pride in the dry steam coal mined from its central valleys, which powered the ships of the British fleet. Times journalist Ivor Thomas commented in 1934:

It is no exaggeration to say that the Industrial Revolution was founded upon coal, and without coal Great Britains remarkable industrial advance in the nineteenth century would not have been possible. On sea and land, coal for a century and a half knew no rival.

As George Orwell emphasised in The Road to Wigan Pier three years later,

The machines that keep us alive, and the machines that make machines, are all directly or indirectly dependent upon coal. In the metabolism of the Western world the coalminer is second in importance only to the man who ploughs the soil.

He marvelled at the endurance of the miners. How easy it was to forget that their lamp-lit world down there is as necessary to the daylight world above as the root is to the flower.

Like the man who ploughed the soil, the coalminer lived and worked away from the towns and cities. Whereas factories were associated with an urban way of life, the mines were located within distinct coalfields , where miners were easily the dominant occupational group. It was a world apart. In his autobiography, the Durham miners leader John Wilson recalled a miner who visited London in the 1860s and, on announcing that he was a pitman, was greeted with incredulity, and marched around the public house to be observed. The onlookers were surprised that he walked upright, having previously believed that miners could only walk in a doubled-up posture owing to the cramped conditions of their work and their continued residence underground. Such beliefs persisted well into the twentieth century. During the Second World War, children from London were lodged in the mining villages of South Wales as evacuees from the Blitz. Every mining village, or so it seems, had at least one account of a child who expressed surprise at seeing miners above ground. As in the nineteenth century, there existed a widely held view that miners lived in underground caves.

The combination of social separation and arduous work performed by men alone, in difficult and often dangerous conditions, were important elements of a paradoxical occupational culture amongst the miners. More than most men, observed social scientist Mark Benney from a Durham mining village in 1946, the miners had a sense of the past.

Their fathers and grandfathers had been miners, and had talked of their craft and out of the long evenings of pit talk reaching back through generations had developed something like a tribal memory.

Similarly, as Tony Hall, later Lord Hall, director general of the BBC, noted in his book King Coal: Miners, Coal and Britains Industrial Future (1981), the miners will describe at length the horrors and the hardship of mining.

Some of the tribal memory was composed of local genealogies; other parts were made up of accounts of trade union struggles, of leaders good and bad, of owners and of managers. The Labour Party also had a role to play, for remarkably, it was in these isolated coalfield areas that the Party found the heartland of its support. Durham and South Wales became synonymous with a Labourist form of politics, one held together at times uneasily by the separate but supposedly complementary interests of the trade unions and the Party. Miners leaders from Durham and South Wales were pivotal to national coalmining trade unionism, including at the time of the 1926 General Strike and the 1944 formation of the National Union of Mineworkers, while six leaders of the Labour Party have represented constituencies in these areas: Keir Hardie, Ramsay MacDonald, James Callaghan, Michael Foot, Neil Kinnock and Tony Blair.