Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2017 by David W. Meyers, Elise Meyers Walker and Nyla Vollmer

All rights reserved

First published 2017

e-book edition 2017

ISBN 978.1.62585.812.2

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016953258

print edition ISBN 978.1.46713.549.8

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the authors or The History Press. The authors and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

For my grandson, Ford.

Tag, youre it!

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Everyones a historian in the Hocking Valleyor at least it seems that way. As a group, they are uncommonly generous with their time, knowledge and collections. We would like to thank Mike Tharp for the photographs from the collection of his late brother, Wesley Tharp; William E. Dunlap; Cheryl Blosser/New Straitsville History Group; Nyla Vollmer, Bruce Warner; and the Columbus Citizen/Citizen Journal Collection at the Grandview Heights Library. Evelyn Keener Walker and Cheryl Blosser deserve special recognition for their editing advice.

We also benefited indirectly from the work of historian Dr. Ivan Tribe of Rio Grande University and John Winnenberg of the Little Cities of Black Diamonds Council, both of whom have done so much to preserve and promote the history of this region. Along with Cheryl, Nyla and other true believers, they have been striving for decades to develop the region into a tourist destination, thereby ensuring its continued existence as a living museum. It hasnt been easy, and its far from done. Perhaps this book will help.

INTRODUCTION

The next thing you will call to mind is that this coal burns and gives flame and heat, and that this means that in some way sunbeams are imprisoned in it.

Arabella B. Buckley, The Fairy-Land of Science (1890)

Coal made America great. Our nation was built on itliterally and figuratively. Blessed with some of the largest and richest coal deposits in the world, the United States evolved into an industrial powerhouse during the second half of the nineteenth century thanks to this organic sedimentary rock. For better or worse, the acquisition, transport and processing of coal shaped the development of our cities and reshaped the appearance of the land. Coal determined the location of towns. Coal dictated the routes of canals and railroads. Coal influenced the evolution of society. In recognition of its value, lumps of coal came to be called black diamonds.

During the American Civil War, Ohio evolved into a major industrial center when three ingredientscoal, iron and steamwere brought together. Coal was used to make iron, iron was used to make steam engines and steam engines were used to mine and transport coal. The states premier industriessteel, rubber, glass and claywere all heavy consumers of coal. When Samuel Harden Stille called his history of the Buckeye State Ohio Builds a Nation, it wasnt far from the truth.

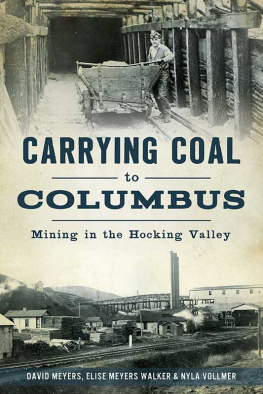

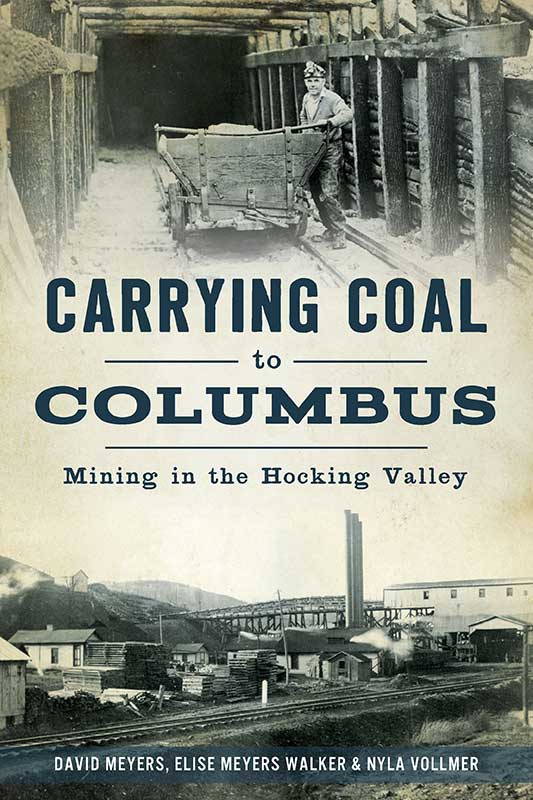

In Carrying Coal to Columbus: Mining in the Hocking Valley, we take a look at the nearly forgotten role that Columbus played in opening up the coal fields of the Hocking Valley, helping to fuel and finance the Industrial Revolution. The existence of coal deposits in the Ohio Country had not gone unnoticed by the regions earliest visitors, particularly where there were exposed outcroppings that could be easily exploited. The word coals appears adjacent to the Hocking River near present-day Athens County on A Map of the Middle British Colonies in America, published in 1755. These deposits formed part of the vast Appalachian Bituminous Coal Field, which underlies much of Ohio, as well as states to the east and south.

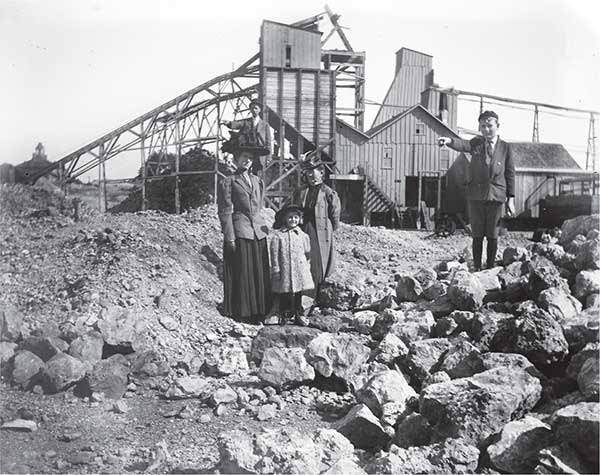

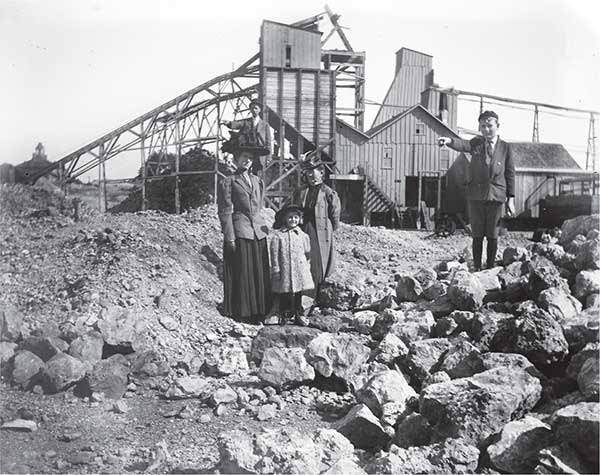

A family outing to an Ohio coal mine. Authors collection.

The availability of coal alone does not make for a coal industry. It had to be first dug out of the ground and transported to market. The Ohio mine owners were feudal princes at best and robber barons at worst. They carved out kingdoms in the hills and hollows of the Hocking, Mahoning and Tuscarawas Valleys and endeavored through an unending series of mergers and acquisitions to consolidate their power. They amassed, and sometimes lost, huge fortunesobtained through what some might call immoral and unethical business practices, while others would chalk it up to pure, unfettered capitalism. As is usually the case, the truth lies somewhere in between.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, there were an estimated fifty thousand workers and their families living in the mining towns that dotted the counties of Athens, Hocking and Perry. Today, the number has dwindled to about fifteen thousand. In most cases, when the mines played out or were abandoned, the town followed suit as the miners moved on in search of work. The communities that developed more diverse economies have managed to survive, if not exactly prosper, reflecting the general economic malaise that characterizes that corner of Appalachia.

Many Ohioans are proud to be descended from these intrepid people. As the late Columbus Dispatch columnist Mike Harden, the grandson of a coal miner, grimly observed: Their collective heritage tells the story of men who, for decades, went to work in the dark and came home in the dark, their world illuminated mostly by the candlepower atop their miners caps. Dying was the only way for them to move up in the world, from the deep shafts they worked to the shallower sod of their graves.

Joining me in telling this story are my daughter and frequent collaborator, Elise Meyers Walker, and our friend, Nyla Vollmer, who has been active in collecting and documenting the history of the region for many years. It is our hope that by chronicling the development of these coal fields through the prism of the coal barons and union leaders, many of whom made their homes in Columbus, we will renew interest in this vanishing part of our history and encourage others to join the efforts to preserve and restore the remnants of these Hocking Valley mining townsthe Little Cities of Black Diamonds.

DAVID MEYERS

CHAPTER 1

FITS AND STARTS

The town is clean and pretty, and of course is going to be much larger. It is the seat of the State legislature of Ohio, and lays claim, in consequence, to some consideration and importance.

Charles Dickens, American Notes (1842)

On the whole, Charles Dickens had been disappointed by his first tour of the United States. The country was simply too backward for his tastes and made the thirty-year-old writer homesick. Viewed in that light, his mention of Columbus, though brief, was surprisingly positiveallowing for a measure of his usual sarcasm. Had he visited the town twenty years earlier, however, it is unlikely he would have been as charitable. It was not particularly clean or pretty. And its prospects did not look especially bright.

The years 1819 and 1820, to 1826, wrote William T. Martin, were the dullest years in Columbus [history]. Martin would know. He was the mayor from 1824 to 1826, as well as the towns first historian. Little more than a crossroads carved out of nearly unbroken forest, Columbus started out with no human inhabitants and wouldnt officially become a city until 1834, when the population topped four thousand. But from 1820 to 1825, business was at a virtual standstill. A great depression had shaken the local real estate market. Money was hard to come by, and numerous lots went unsold at a sheriffs sale, even at two-thirds of their appraised value.

Next page