Published in Great Britain in 2016 by Shire

Publications Ltd (part of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc),

PO Box 883, Oxford, OX1 9PL, UK.

1385 Broadway, 5th Floor New York, NY 10018, USA.

E-mail:

This electronic edition published in 2016 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Bloomsbury is a registered trademark of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

2016 Richard Hayman.

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Every attempt has been made by the Publishers to secure the appropriate permissions for materials reproduced in this book. If there has been any oversight we will be happy to rectify the situation and a written submission should be made to the Publishers.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Shire Library no. 836.

ISBN: 978-1-78442-120-5 (PB)

ISBN: 978-1-78442-121-2 (eBook)

ISBN: 978-1-78442-122-9 (ePDF)

Richard Hayman has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this book.

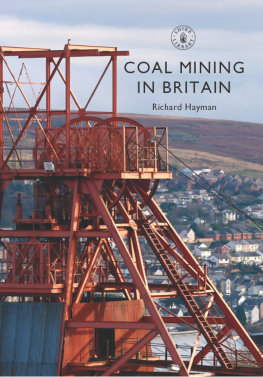

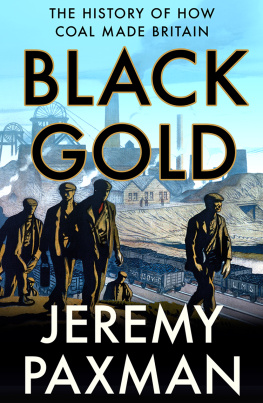

COVER IMAGE

Front cover: The Big Pit National Coal Museum at Blenaevon ( The Photolibrary Wales / Alamy Stock Photo).

TITLE PAGE IMAGE

Screening in the nineteenth century is shown in an advert from the Colliery Guardian. Coal was tipped from tubs on to the screens and fed into railway wagons beneath them.

CONTENTS PAGE IMAGE

As underground working became more extensive in the early twentieth century, manriding cars powered by electricity were introduced to move miners quickly to the coal face.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Permission to reproduce illustrations has been given by the following: Archive Images, .

Shire Publications is supporting the Woodland Trust, the UKs leading woodland conservation charity, by funding the dedication of trees.

The engine house and pit-head buildings at the former Barnsley Main Colliery in South Yorkshire, which closed in 1991, are among the few colliery buildings to escape the rapid clearance of coal-industry sites in the late twentieth century.

BLACK GOLD

The material source of the energy of the country the universal aid the factor in everything we do. That was how the Victorian economist W. Stanley Jevons described the coal industry in 1865. Coal had been mined for centuries but in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the coalfields became Britains industrial heartlands. Britain became the first nation to base its economic civilisation on mineral fuel and rose to be the worlds largest economy. How this came about is quite simple. Coal became the fuel of the iron industry, by far the most important of the metals trades in Britain. In turn the iron industry gave us fuel-hungry steam engines, and the railways and ships by which coal could be distributed cheaply at home and abroad.

The decline of the coal industry in the second half of the twentieth century was rapid. When it was formed in 1947 the National Coal Board (NCB) was responsible for over 1,500 collieries. Coal was central to the vision of a bright future for Britain and its industry, but it was soon eclipsed by oil and very quickly it has been consigned to the past, with a reputation as a dirty fuel and a significant contributor to global climate change.

Clearance of collieries and landscaping of old spoil tips has removed the industry from its former dominant presence in the landscape, so that in parts of the coalfields the only reminders of the former industry are subtle ones such as old miners institutes or the sterile landscape of re-graded spoil tips. Other aspects of coal-mining life have disappeared completely. The special language of the goaf (the space where coal had been cut from), the rolley-way (or underground tramway) and the dib-hole (the sump for collecting water at the bottom of a shaft) no longer means anything. The skills of the face workers known mainly as hewers, but as haggers in Cumberland, pikemen in Shropshire and getters in Yorkshire have also vanished, a reminder that industrial decline brings with it cultural as well as economic losses.

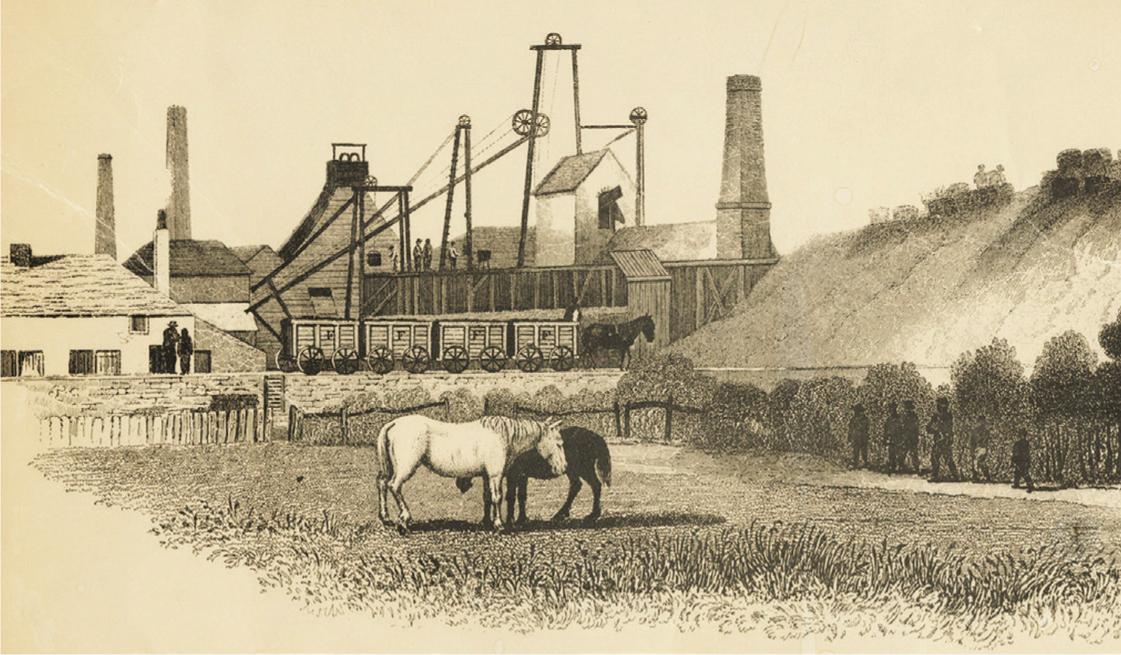

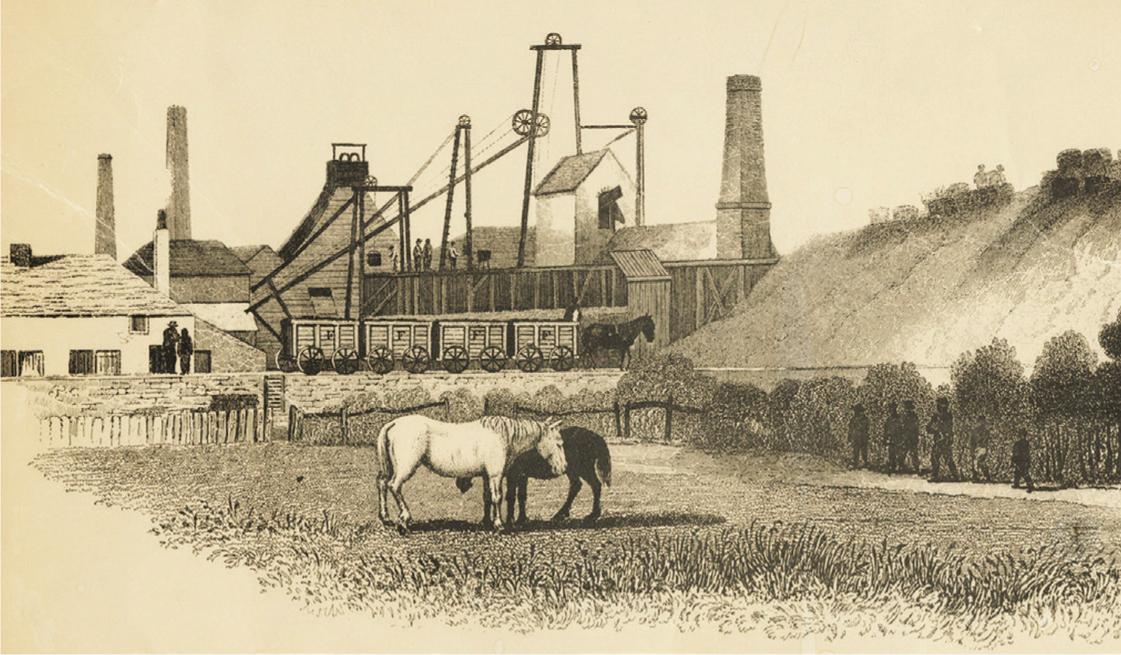

Wideopen Colliery, Northumberland, viewed here in 1844 by Thomas Hair. Until the nineteenth century the northeast was the dominant region of coal production.

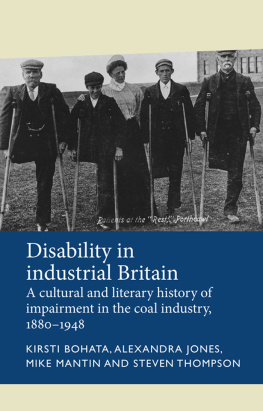

Nevertheless, there is still a rich heritage of coal mining in Britain, albeit one that engenders mixed feelings. It produced a skilled workforce vital to the nations interest, but in the process miners endured hard times and appalling sufferings. Outside of the coalfields the miner has always been something of a mythical figure, the consequence of which is that society has often viewed him (occasionally her) unsympathetically. In modern times this has been partly a political response, since coal miners became a recognised force in the nations political life, forming a vociferous and often militant lobby for better working conditions and a decent standard of living. But miners have always seemed like a community apart, a fact determined by the nature of the work and by the geographical locations in which the industry was confined.

Chatterley Whitfield, near Stoke-on-Trent, is the most extensive of the surviving collieries in Britain, although coal was last brought to the surface here in 1976.

The dangers of coal mining have cast a shadow over the history of the coalfields. The worst British peacetime disasters have happened in the coal industry. Disasters can be measured in numbers, on which basis the worst event occurred in 1913 when 439 men and boys from the Universal Steam Colliery at Senghenydd, in South Wales, were killed by an underground explosion. Or it can be measured on a scale of unimaginable horror, in which case nothing could eclipse the disaster at Aberfan near Merthyr Tydfil in 1966, when 144 people, 116 of them school children, perished under a collapsed colliery tip. In the face of these tragedies the coalfields produced communities with a distinct politics and culture, perhaps best expressed now in the still-flourishing Durham Miners Gala, who were proud of their contribution to Britains economic wellbeing.

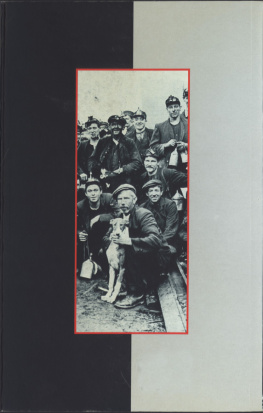

The last dram of coal sums up the pride in mining communities and their sense of loss at its decline.

BELL PITS AND HORSE WHIMS

Coal is a mineral fuel. It belongs to the geological period known as the Carboniferous, and was laid down between 306 and 313 million years ago, when Britain enjoyed a tropical climate. It was formed from thick layers of peat in river deltas that slowly subsided under their own weight and were eventually compressed to form coal it took a layer of peat 10 metres thick to produce a coal seam 1 metre thick. Often the deposition of peat was interrupted by layers of sediment on which another phase of peat would later form, which is why coal is found as seams in sedimentary rocks. Subsequently the individual seams, known as coal measures, were subject to various geological processes, like uplifting, faulting and folding, which have had two major consequences. Coal seams outcrop on the surface in all of Britains coalfields, except in Kent, but the unpredictable nature of coal seams means that mining operations have often been confounded by geological faults.