CONTENTS

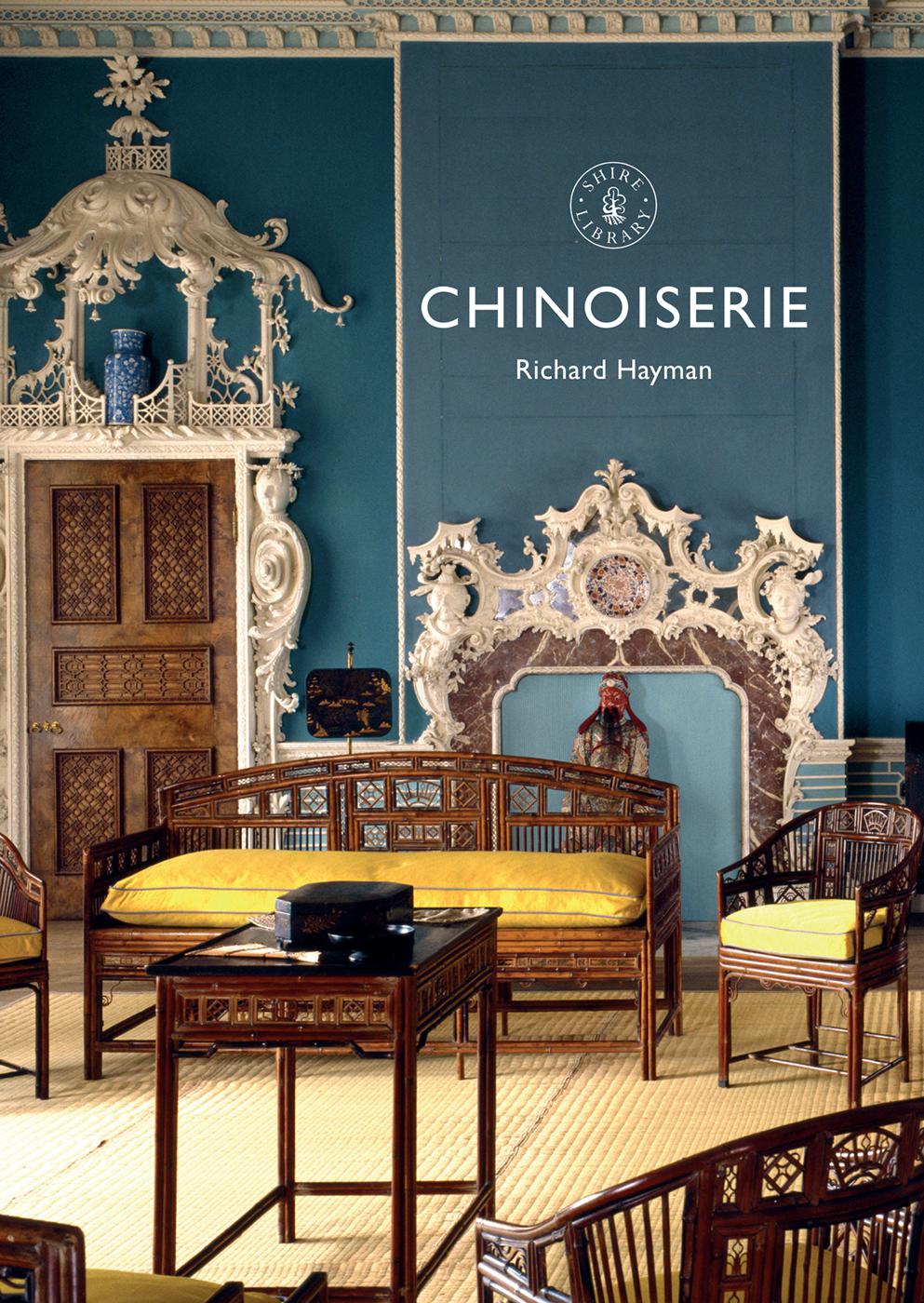

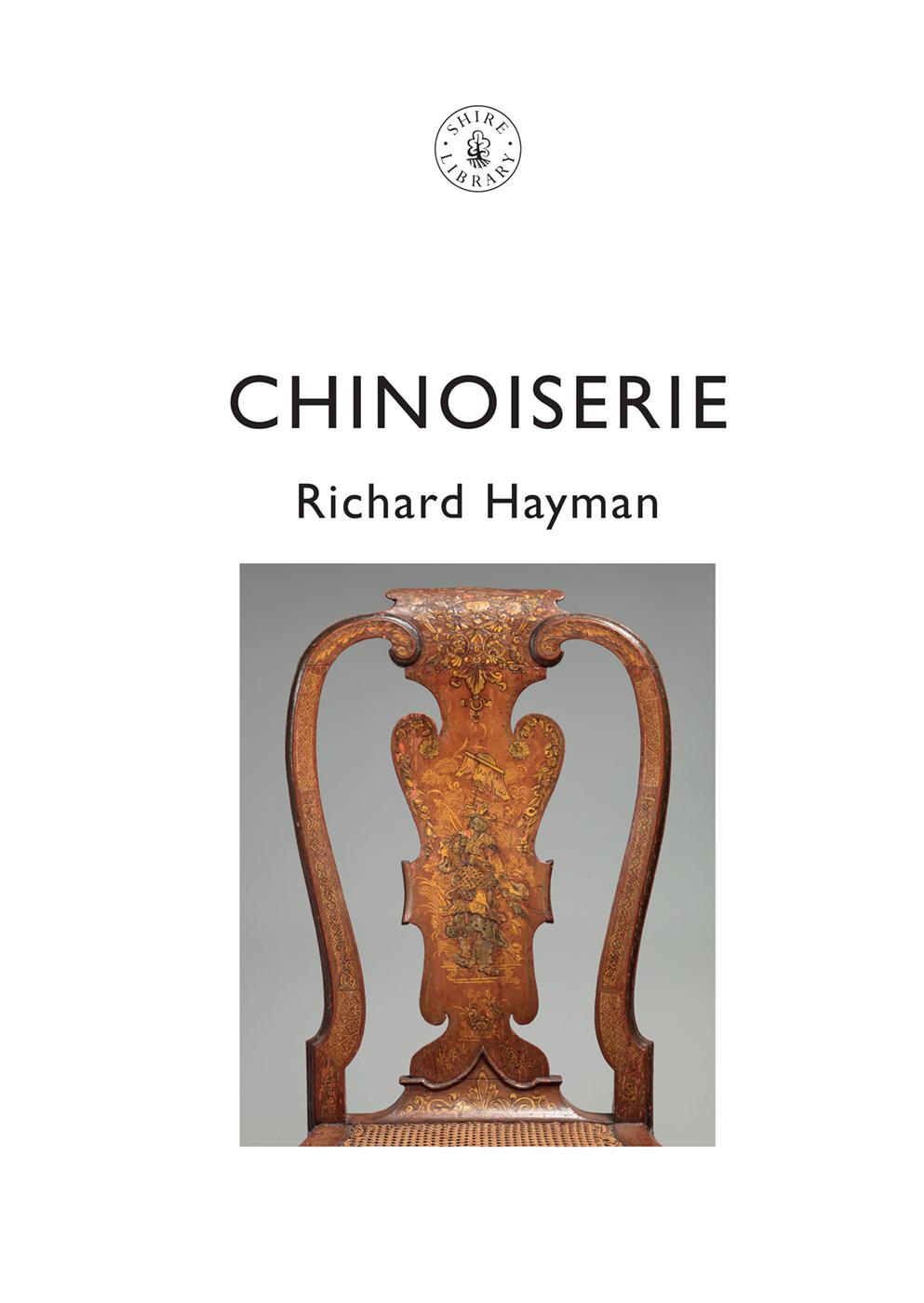

CHINESE WHISPERS

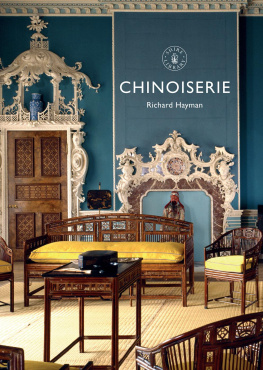

C hinoiserie was a craze of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, a period that overlapped with the beginning of the Industrial Revolution and modern consumer society. Interior decoration, fabrics, table wares, ornaments and garden architecture were all produced in Chinoiserie styles at a time when more and more people were able to afford them. Asian culture impressed itself upon European culture to the extent that its signature products, porcelain and lacquer, are known in English as china and japan. As the celebrated bluestocking Elizabeth Montagu (17181800) remarked in 1749, sick of Grecian elegance, or Gothic grandeur and magnificence, we must all seek the barbarous [taste] of the Chinese. In the domestic world Chinoiserie flourished in a period of multiple competing styles. As one wit put it in 1786, a well-educated British gentleman is of no country whatever: he talks and dresses French, he sings Italian his house is Grecian, his offices Gothic, his furniture Chinese.

Chinoiserie was not an authentic version of China, something that consumers always knew in the back of their minds. Instead it was part of an exotic Orient conjured from the travel writings of missionaries, diplomats and traders over several centuries, about a part of the world that was experienced only through the imagination. Travel in China for Europeans was severely restricted, which only served to heighten its mystique. At the height of the craze for Chinese things in the eighteenth century the average European had a very hazy idea of the geography of Asia; few could have distinguished between work from China, Japan, India and Thailand (or Siam, as it was then known). In that sense Chinoiserie is a vague term and in practice encompasses material culture of the Far East, including lacquer and pottery from Japan and Indian chintz. When auction sales of Chinese goods were advertised in the London press, they were often referred to as Indian goods, largely because they were imported by the East India Company or its officials.

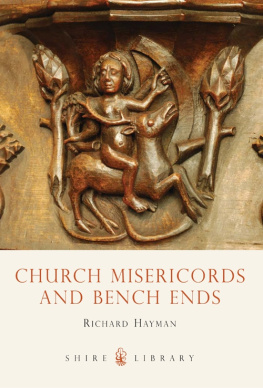

A Chinese family is depicted in this piece of ornamental porcelain made by the St James Porcelain Factory in London in the 1750s.

By contrast, manufacturers in Canton had a much clearer idea of what version of China the Europeans wanted, and set about providing goods tailored to the European export market. But demand for oriental products far exceeded supply, a shortfall that was met by home production. Chinoiserie therefore covers two kinds of manufactured goods: those produced in China for the European market, and goods manufactured in Britain and other European countries under Chinese influence.

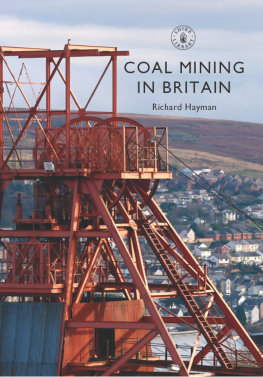

Eighteenth-century Britain was a nation of social mobility. Chinese goods, along with other exotic imports like sugar and chocolate, had originally been luxury items and a marker of elite status, but soon broadened to incorporate a wider section of society, including socially ambitious people whose wealth was derived from trade. Wealth derived from the plantations of the West Indies was invested in Chinese fantasies for the home. In the 1690s Queen Mary had been renowned for her magnificent collection of porcelain, but by the 1730s porcelain vases were a regular fixture on the mantelpieces of town and country houses. Aristocrats purchased porcelain because they saw it in the Queens cabinet, while the nouveaux riches became attracted to it because it was an emblem of the aristocratic taste to which they aspired.

A conversation piece painted by Arthur Devis in 175051 shows a fashionable couple with the tea things set out on a table, and a large porcelain vase in the fireplace.

Chinoiserie was not a fashion universally admired. For some of its detractors, like The Spectator editor Thomas Addison, writing in 1712, Chinese goods represented the kind of novelty that soon wears off. Chinoiserie was often regarded as frivolous, superficial and feminine, qualities that were synonymous in many contemporary minds. Certainly it never tried to compete with the classical style for its gravitas and rationality, even though it co-existed and complemented the ornamental classical style known as rococo. For some of those lucky enough to have received a Latin education and to have taken the Grand Tour of Europe, the classical remained a superior form of art and civilisation. Chinoiserie, by contrast, did not need any cultural erudition for its appreciation and could be enjoyed by new and old money alike.

William Hogarths series of prints entitled Marriage A-la-Mode (174345) included this image of a bored wife in a room full of Chinoiserie items, such as a tea set, ornamental porcelain and a Chinese fire screen.

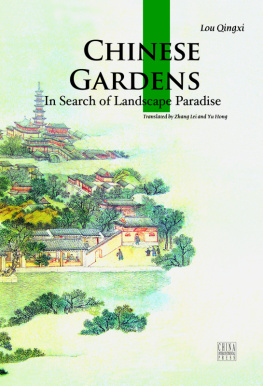

It was Marco Polo who introduced China to the Western world. He was in China between 1271 and 1295 and served under the great Mongol Emperor, Kublai Khan. Marco Polo encountered many places that would not be explored again by Europeans until the nineteenth century and planted ideas that took root in the European imagination. He described an empire more vast than Europeans could imagine, in which there were palaces of immeasurable splendour, decorated with images of exotic birds, trees and flowers, a civilised world seemingly at peace with itself. Marco Polos account was largely backed up by Odoric, a Franciscan Friar who lived in China for three years in the 1320s. After the Ming dynasty was established in China in 1370 it became closed to outsiders until the Portuguese established trading there in the early sixteenth century, from which time the Chinese accepted a small number of tribute embassies, as well as a small amount of trade.

The Chinese story of Sima Guang, about an eleventh-century scholar who saved his friend from drowning, is adapted to this bowl produced c.1755 at the Chelsea Porcelain Factory.

Europe learned of Chinas civilised manners, its beautiful and restful gardens, and of the philosophy of Confucius. Partial glimpses of China reported by traders and missionaries, many of which were published in English, only made the Orient seem more alluring. For example, Johan Nieuhof wrote a full account of a failed Dutch mission to the new Qing dynasty in 1644. He described pagodas, timber and woodwork protected by lacquer, informal gardens with rockeries and pools, and flowers that would be unknown in Europe until the nineteenth century. He also gave an account of a drink known as cha, later to be known in Europe as tea. By the eighteenth century there were enough Chinese travel books to line whole bookshelves and China made the transition from an imagined world on the printed page to a source of desirable objects for the home.